This post is about Johnson and Appleyards, not many people will have heard of it, but that shouldn’t have been the case. Life is full of what ifs. What if things had been done differently? If they had been, then we might have been fondly remembering Johnson and Appleyards as we do Cole Brothers and Walsh’s.

Our story starts on 10 February 1909 when Councillor Walter Appleyard received a cable from Kobe in Japan. It was from his brother, Frank, and informed him that their older brother, Joseph, had died. The fact that it happened in a foreign country was no surprise because Joseph had travelled extensively to Australia, South Africa, and South America, and this latest excursion which started five months previous, had taken in Egypt, India, Burma , and China. The next stop would have been Canada before heading home.

The news might have suggested that this was the first stage of failure for Johnson and Appleyards, cabinet designers and manufacturers, upholsterers, decorators, undertakers, carpet warehousemen, colonial merchants, and exporters, but the decline had already begun, not that anybody had realised it.

The three Appleyard brothers, Joseph, Walter, and Frank were the sons of Joseph Appleyard, a Conisborough cabinet maker, who had a business until 1872, when he established J. Appleyard and Sons at Westgate and Main Street in Rotherham which the brothers ran.

In 1879, the brothers took over the Sheffield furniture-making business of William Johnson & Sons, with premises on Fargate, and renamed it Johnson and Appleyards. It was a bold move, but within a few years the business needed bigger premises to display its furniture.

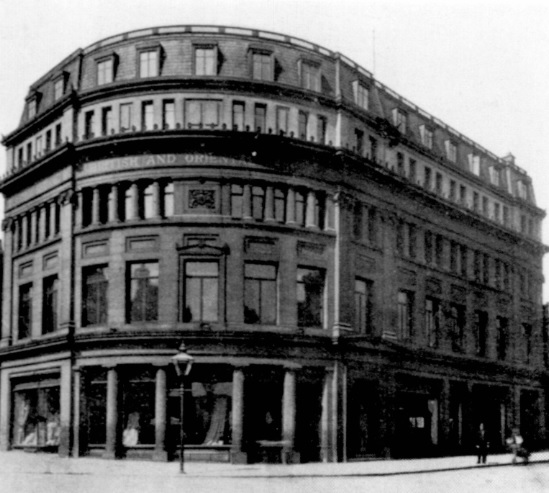

They chose a prime site at the corner of Fargate and Leopold Street and employed architects Flockton and Gibb to design an impressive showroom built in Huddersfield stone with a mixture of giant ionic and stubby doric pilasters on its first and second floors.

The building was completed in 1883 and survives as Yorkshire House, where Barker’s Pool (then an extension of Fargate) turns the corner into Leopold Street. The only remaining trace of Johnson and Appleyards is a stone plaque, high up, that states ‘Cabinet makers to HRH The Prince of Wales’. For some reason, the building has failed to get listing from Historic England, and we now know it as home to jewellers H.L. Brown.

Johnson and Appleyards were the only firm to supply the complete range of domestic furnishings, selling their own furniture as well as famous names like Chippendale, Sheraton, Louis Quatorze, and Louis Quinze. In the basement, were showrooms for carpets, linoleum, bedlinen, and blankets. The ground floor held wallpapers together with general goods, along with the counting house, and stables and carriage/van sheds at the back. The first floor was dedicated to furniture with workshops behind, and on the second floor, further showrooms with draughtsmen’s offices and decorators’ shops to the rear. The third floor housed gilders’ workshops, polishers, upholsterers and bedding makers.

Johnson and Appleyards became a limited company in 1891, and the following year the building was extended, with an attic story and mansard roof built to create more retail and workshop space. At the same time, manufacturing was moved to a four-storey building on Sidney Street.

Johnson and Appleyards achieved national and international recognition with a ‘Prize medal awarded for Superiority of Design and Workmanship’ (York, 1879) and a gold medal award at the Paris Exhibition (1900).

There is a clue that business at Johnson and Appleyards had dwindled, because in 1906 the firm had moved to smaller premises next door on Leopold Street. While retaining ownership of the showcase corner property, it was leased at a handsome price to A. Wilson Peck & Co, wholesale and retail dealers of pianos, organs, and musical goods. (Wilson Peck – Beethoven House – another fascinating story for another day).

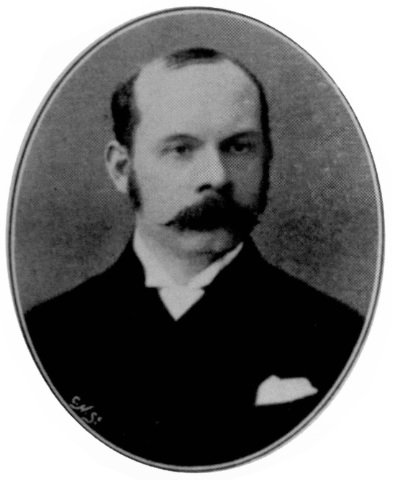

Joseph Appleyard (1848–1909), as senior partner, was the only brother to remain active in the firm, and although he remained a director, Walter had other business interests and would become Lord Mayor, while Frank had left by 1905.

Joseph’s marriage to Sarah Flint Stokes had given him eight children, none of whom had much interest in the business. Only two of his four sons, Joseph (1881-1902) and Harry (1876-1954) showed any enthusiasm. Joseph Jnr was employed by Wallis & Co, linen drapers, in Holborn, but drowned aged twenty-one in a boating accident on the Thames, while Harry, who had trained at Harrods in London and Maple & Co in Paris, joined the firm but left shortly after his father’s death. His other two sons joined the services, to avoid joining the firm and collaborating with their father.

A biography of Joseph Appleyard states that he was a strong conservative but had no desire to enter politics. He was a member of the King Street and Athenaeum Clubs, as well as being an affiliate at the Wentworth Lodge of Freemasons.

Julie Banham’s ‘Johnson & Appleyards Ltd of Sheffield: A Victorian family business’ (2001) hints that Joseph Appleyard was prone to violence and regularly beat his sons, while his wife turned to drink and became an alcoholic.

All these years later, it is difficult to determine the type of person that Joseph might have been. At that time, newspapers filled columns with obituaries of local dignitaries, often shown in positive light, but Joseph’s death had little mention. Is this an indication that there weren’t any kind things to say about him? He was cremated in Japan and his ashes interned at Fulwood Church.

Johnson and Appleyards had built its reputation on Victorian tastes that lingered into the Edwardian period. But the new century meant styles had changed. On hindsight, the firm seemed reluctant to evolve with the times, and while sales dwindled, excessive capital was still taken out of the business to fund lavish lifestyles. After Joseph Appleyard’s death, the management team struggled to find a long-term strategy, and two world wars did nothing to improve its fortunes.

The end of Johnson and Appleyards was inadvertently caused by German bombs that rained on Sheffield during 1940. One of them destroyed John Atkinson’s store on The Moor and it was forced to seek alternative premises in the city centre. It bought all the shares in Johnson and Appleyards, if only to secure the Leopold Street building, and would remain until its replacement store was built on The Moor. The old Johnson and Appleyards shop would eventually be swept away, along with the Grand Hotel, to build Fountain Precinct in the 1970s.

Here’s the surprise. Did you know that Johnson and Appleyards still exists, if only in name? Its shares are registered to Atkinsons on The Moor.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.