“I saw him in the cells at the Town Hall. he appeared very delirious there: his face was swollen, and his eyes had turned yellow. I’m afraid the wretched cell in which he was placed had turned him delirious: it was a most wretched place. He was innocent of the charge against him; but, of course, it preyed upon his mind, and being in that wretched place would tend to make him delirious. The charge against him weighed heavily on his mind.”

These were the words of Henry Levy in 1862. He was a clothier on the High Street, and he was speaking at the inquest of his friend and neighbour, Benjamin Cohen, a jeweller.

Days before, Mr Cohen, aged fifty-five, had been taken into custody on the charge of having stolen gold and silver watches in his possession. They had been taken in Swansea five years earlier, the crime unsolved, until detective officer Brayshaw in Sheffield received information that watches bearing the victim’s name were in the ownership of Cohen.

Mr Cohen was released on bail, but confined himself to bed, and would not eat.

Henry Jackson, his surgeon, was summoned on the Tuesday morning.

“I found him lying on his right side in bed. The clothes were wrapped around him in a disordered state. His face was pale, his eyes closed, and his skin cold. On turning down the clothes I found his hands bloody. His shirt was saturated in blood. On turning him on his back I found a razor fully open and bloody. On lifting his shirt, I found a large portion of bowels protruding, with a considerable quantity of blood under and about him. I did what was needful in replacing the bowels and relieving him.”

Cohen died from his self-inflicted wounds that night.

“I had been with him all day,” added Mr Levy. “He kept saying ‘position, once, twice; I did it nicely.’ I don’t know what that referred.”

With tradition, Mr Cohen was buried the next day. A hearse and two mourning coaches trotted through the streets of Sheffield until it arrived at Bowdon Street, where there was a small Jewish cemetery. He was interned and became one of the last people to be buried here.

Unbelievably, this sad story became known after a friend made a chance remark in the pub. He’d been working on the conversion of Eyewitness Works on Milton Street into trendy apartments.

“If you look at Google Maps, it shows that there is a cemetery nearby, or at least there was.”

To prove the point, he showed me his mobile phone and zoomed in on the area around Milton Street. Sure enough, on the road that runs parallel to Fitzwilliam Street, between Charter Row and Milton Street (near Corporation), was a red label showing Bowdon Street Cemetery. I’ve since tried this on my own phone and can find no evidence of it.

But my friend is right, because there was a Jewish cemetery on Bowdon Street, but no trace of it remains.

According to Sheffield Archives, the earliest reference of Jews in Sheffield is in the trade directory of 1797. It grew from about sixty people, belonging to ten families, in the 1840s to about 800 in 1900. This was due to immigration, those fleeing from persecution in Eastern Europe, and settling in Sheffield on their way from Hull to Manchester, Liverpool and eventually America. Benjamin Cohen had been born at Posen, then in Prussia, now part of Poland. Most families lived around the Scotland Street and West Bar area, many becoming watchmakers, jewellers, and tailors.

“The Sheffield Hebrew Congregation is about 120 years old,” wrote Rabbi Barnet I. Cohen in 1926, “though there were a few Jewish families here some time before the congregation was formed. One of the first acts was to provide a burial ground.” This turned out to be a small plot on Bowdon Street that was suitable for the handful of Jewish residents at the time.

The land was acquired in 1831 but closed in 1874, although burials took place afterwards where a plot had been reserved.

“The present cemetery is in Blind Lane, Ecclesfield,” reported Rabbi Cohen (who might have been a relative of Benjamin Cohen), “and there is also a cemetery in Walkley belonging to the Central Synagogue on Campo Lane.”

“The congregation has constantly had trouble through the desecration of the graves by urchins, who not content with climbing over the (high) walls, actually found delight in breaking up the tombstones and digging up the graves, and so recently had a stout door erected and pieces of glass placed on top of the walls.”

The graveyard was surrounded by industry, stables, and back-to-back houses, one of which belonged to Percy Richardson in the 1920s.

“A cemetery enclosed by high walls and the happy hunting ground for adventurous boys. The graveyard is spread over with stones and old tin cans.” It was described as the untidiest graveyard in Sheffield.

I mentioned Bowdon Street Cemetery to my 94-year-old dad, who couldn’t have been one of Rabbi Cohen’s urchins but may or may not have been a wartime urchin and remembers it from the time he lived on Milton Street.

The graveyard survived until 1975 when Sheffield City Council imposed a compulsory purchase order on the site, the ‘mortal remains of 35 grave spaces re-interred in Colley Road, Ecclesfield’.

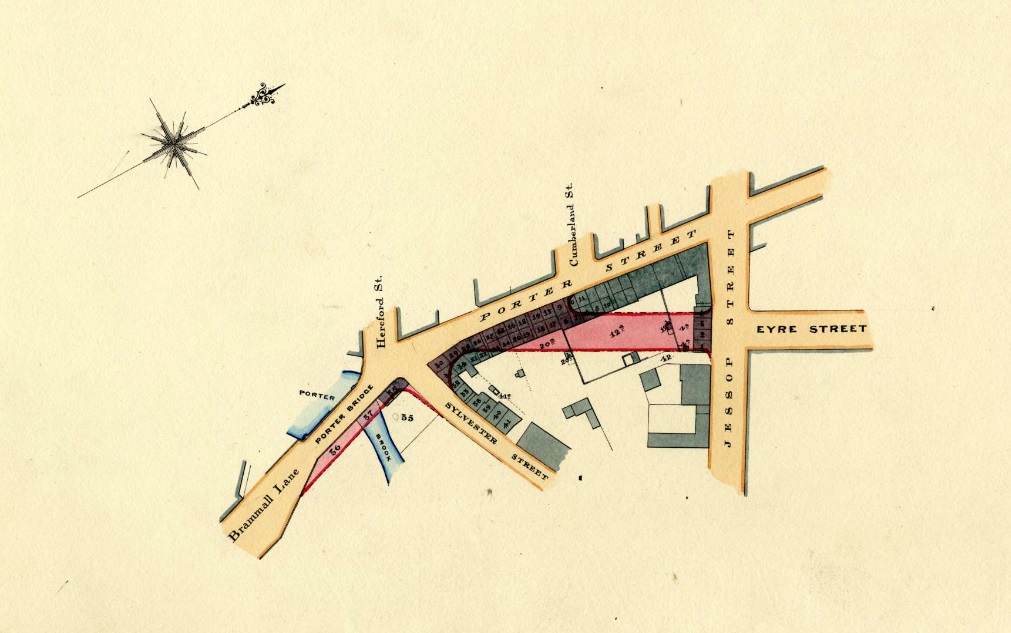

Through an old map I’ve managed to find the exact location of Bowdon Street Cemetery, and on a rainy day this week, I visited the old site.

Bowdon Street is at the back of the NHS Substance Misuse building that fronts Fitzwilliam Street. The tiny plot would have run from Bowdon Street, the site partly landscaped, and would have taken up the back end of the Fitzwilliam Centre as it is now.

I thought about the tormented soul of Benjamin Cohen and trust that his remains are at peace in Ecclesfield.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.