Let me take you down the subway at the roundabout which links Eyre Street, St. Mary’s Road, Bramall Lane, and St. Mary’s Gate. Once you get into its tree-lined centre, stop for a moment, and consider that several decades ago you would have been standing in the corner of a graveyard.

It is true.

The construction of Sheffield’s ring road required the widening of St. Mary’s Road and a roundabout. It meant that the graveyard at St. Mary’s Church was deprived of land, and where graves once stood, the subway has become a popular route for students and football fans journeying to Bramall Lane. Come down here at night at your peril because it is also the haunt of muggers and the like.

In a few years’ time, St. Mary’s Church will celebrate its bicentenary and where other big churches have faltered, it will be content that it still operates as a place of worship.

Let us start at the beginning.

The year is 1818 and to celebrate the recent end of the Napoleonic Wars, parliament passed the Act for Building New Churches, allocating £1 million for the task; the buildings that resulted were often known as the Waterloo churches.

The church was in crisis, a situation brought about by changing demographics and altering religious affiliations: the surge of the working-class population in major cities, especially in the north, and the drift to nonconformity.

The Church Building Commission turned to the government Board of Works, and its three advisory architects, John Nash (1752–1835), John Soane (1753–1837), and their junior, Robert Smirke (1780–1867), to set guidelines and advise on practicalities.

It stated that no church should cost more than £20,000, and by the end of the Commission’s term, in 1856, some 600 new churches would stand across the country.

In Sheffield, three churches were commissioned under the chairmanship of Rev. Thomas Sutton of Sheffield’s Church Building Committee– these were St. George’s, Portobello, St. Philip’s, Netherthorpe, and St. Mary’s at Highfield.

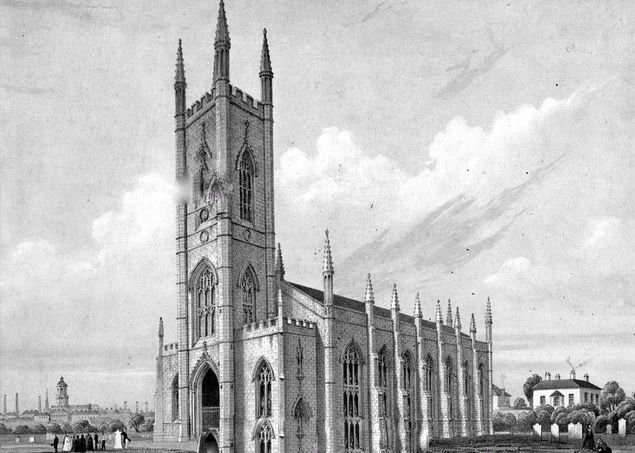

St Mary’s Church was the last of the three to be built and was constructed on land that had been gifted by Henry Charles Howard, the 13th Duke of Norfolk (also the Earl of Surrey). The foundation stone was laid by his wife, Lady Charlotte, Countess of Surrey, using an engraved silver trowel, in front of a huge crowd.

“With this trowel, Charlotte, Countess of Surrey, laid the foundation stone of St. Mary’s Church, Sheffield, 12 October 1826.”

The foundation stone contained a bottle in which were deposited coins and documents, but a few weeks later, a letter to the Sheffield Independent revealed that the stone had been removed the same night, and the bottle conveyed to the vicar’s house so that it would not be stolen.

The country was amid depression due to suspended credit and impoverished markets and the cutlery industry had suffered badly. For this reason, workmen employed on clearing the site and preparing the foundations were ‘able-bodied and willing minded cutlers’ who had fallen on hard times.

The church was designed by Joseph Potter (1756-1842), a Lichfield-based architect, who early in his career had been employed by James Wyatt to supervise works at Lichfield Cathedral, Hereford Cathedral, St Michael’s Church in Coventry (now St Michael’s Cathedral) and the rebuilding of Plas Newydd, a house belonging to the 1st Marquess of Anglesey. He was the County Surveyor of Staffordshire for 45 years, as well as an engineer for the Grand Trunk Canal Company.

Potter’s eldest son, Robert (1795-1854), supervised the works at St. Mary’s, and he developed an attachment to the town because he opened an architectural practise here and built his home on Queens Road.

Building work was undertaken by Thomas Henry Webster of Stafford and the last stone was laid on top of the pinnacle at the southwest corner of the 140ft tower in November 1828, the occasion marked by the rising of the Standard of England and two other flags.

The church needed a minister and Rev. Sutton, Vicar of the Parish, appointed the Rev Henry Farish, Tutor of Queen’s College, Cambridge, at St. Mary’s in July 1829.

The church accommodated 2,000 people and had cost £13,927, the Church Building Commission covering the cost, as well as contributing £40 towards the cost of a bell in its tower. It was consecrated by the Archbishop of York on 21 July 1830.

However, its four-year construction had not been without its problems, but it took a letter to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph in October 1926, to reveal what had happened.

“By the original plan, the interior of the church was formed by two fine stone arcades into a handsome nave, with clerestory, and two side aisles, each vaulted, groined, and corbelled in stone. And the powerful buttresses, now on each side of the church, were built to take the weight and thrust of the internal vaulting. When the outside walls had scarcely reached the height of the parapet, an order came from headquarters to stop proceedings. It is supposed the million fund was about exhausted, but particulars were kept dark.

“This calamity completely stultified matters and new arrangements were made to finish the church with the least possible outlay. The result was the present lath and plaster imitation vaulting, supported by long thin cast iron props in lieu of stone pillars. This, I believe was the first and only instance of the use of cast-iron for such a purpose; its use here was owing to cheapness, and although these arrangements were a clever way out of a difficulty, they were always stigmatised by Robert Potter himself as an abortion and architectural curiosity, with which he disliked being associated.”

This revelation is backed by an old document that states that the plumbing, glazing, and imitation of stone on the walls and vaulted roof was by Robert Drury of Howard Street.

St. Mary’s Church had been in semi-rural surroundings. Its construction coincided with the growth of Sheffield, and once the old bridge over the nearby Porter Brook was replaced, the town expanded towards Little Sheffield, a hamlet that once stood in the London Road area that was swallowed up.

A lot has changed since then.

The west part of St. Mary’s was damaged by wartime bombing and was redeveloped by Stephen Welsh into a community centre in 1950. The division of the church was softened by APEC Architects in 1999-2000, who removed the 1950 work and created a new community centre of two floors and a mezzanine that filled all but the chancel and the two east bays of the nave, which is still used for worship.

At the beginning of World War Two, a decision was made to remove the stained glass windows and safely store them. Unfortunately, their location was lost until 2020 when Colin Mantripp, a wood carver from Buckinghamshire, bought what he thought was a box of fragments of stained glass at auction.

When he collected the box, it turned out to be an 8 foot by 3 foot wooden box full of 13 stained glass panels. The outside of the box had St. Mary’s scrawled on the side. After careful research, he discovered that the windows had come from St. Mary’s Church and offered to gift them back providing they could be put back where they belong. The church declined because it wouldn’t have been practical to put them back. The panels are probably from the east window, which was filled with a new commission by Helen Whitaker in 2008.

Finally, as already mentioned by a previous correspondent, let us remember Lily Hawthorne, who was a cleaner at St. Mary’s Church and was murdered here on December 4, 1968. There is plenty of speculation surrounding this tragic incident, but the facts are that Hugh Mason was tried at the Sheffield Assizes in January 1969 on a charge of murder and, after hearing the evidence of three doctors that he was suffering from mental illness, the jury found him not guilty by reason of insanity. He was admitted to Broadmoor Hospital and later transferred to Sheffield’s Middlewood Hospital in 1972.

©2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.

All images / DJP /2024 unless stated.