It was one night last summer, and I was taking photographs of skateboarders who had requisitioned the former Staples car park at the corner of St. Mary’s Gate and Eyre Street. There were about thirty of them, showing off to each other, trying to be cleverer than the next.

A small group noticed my interest and obliged by making their skateboards do remarkable things, but the resulting photos weren’t particularly good and soon forgotten.

Staples had long gone, so had Office Outlet that replaced it, and we forget that Mothercare had a shop here, later home to Theatre Delicatessen. The retail park was emptied, bought by Lidl for a new store, but plans had faltered, and the site had surrendered itself to broken windows and graffiti, hastening the rapid descent into decay.

Wooden gates had been erected, preventing entry into the car park, and allowing skateboarders to takeover.

The recent posts about St. Mary’s Church and Ladies’ Walk made me think about the conversations I’d had that night.

Taking a breather from their enactment, three boys sat on the tarmac, drinking bottled water, and chatting about their hallowed space.

I told them that where they were sitting had once been Ellin Street, still listed on maps, named after Thomas Ellin, who used waterpower from the adjacent Porter Brook where it widened into Bennett’s Dam. Here, he founded Vulcan Works with cutlery shops and a steel furnace, and the makeshift skateboard park was where the dam had been.

“That’s cool,” one said, “the dam disappeared, but the river’s still here.”

He was referring to nearby Porter Brook, and the reason Lidl withdrew their planning application last autumn. The discounter was aggrieved about calls to deculvert the river where it flowed under the site, with the loss of car parking spaces .

On the other side of Porter Brook is St. Mary’s Gate, where I took them to see an information board about an ancient structure called Bramall Lane Bridge. Like many Sheffielders, they had no idea about it, and were surprised to learn that it still existed, yards from where they skateboarded.

“Look here,” one of the boys said, pointing to a tongue in cheek warning on the sign.

“Best not to explore under the bridge as there are rumours that the Old Bramall Lane Bridge troll eats anything, especially with her carefully guarded bottle of Henderson’s.”

When told not to do something, lads of that age will do the opposite.

Days later, I saw them again, and they told me that they’d followed the river under the bridge, and then bottled it for fear of meeting the troll that protected it.

Their reaction is common because people don’t realise that Eyre Street, where it joins Bramall Lane Roundabout, is really built on a bridge that starts at the edge of the former Staples car park and ends on the other side of the dual carriageway near Decathlon.

These days, there is a Friends of Bramall Lane Bridge Facebook group that is responsible for the information board, and for getting the bridge listed on the South Yorkshire Heritage List. That was no mean feat because until the group had applied for its listing, the heritage body was also oblivious to its existence.

But what of its history?

I remembered a letter that had been published in the Sheffield Independent from 1831: –

“Permit me, Sir, through the medium of your valuable miscellany, to call the attention of the Town Trustees and others to this hitherto neglected, though now highly improving part of town. The bridge over the river Porter cannot remain as it is, and if all the owners of adjacent property were to come forward, I am certain the town trustees would not be appealed to in vain for their assistance in connecting Eyre Street, by means of a quadrant or an angle, with Brammall Street. This may be accomplished at considerably less expense than might be at first imagined, and most assuredly it would not only very much increase the value of property in the neighbourhood but would become a highly acceptable substitute for Porter Street, at the entrance to the new part of the town, by throwing open to view that most elegant structure, St. Mary’s Church.”

The letter showed remarkable foresight and within years, a new bridge had been built and Eyre Street eventually connected with Bramall Lane. Had this not been the case, then Bramall Lane might never have become home to Sheffield United FC.

The bridge’s history goes back to days when this was countryside, still a distance from the town that ended where Moorhead is now. At this time, Porter Brook had to be crossed by a narrow wooden footbridge, and horses and carts had to splash through the water to get to the other side.

When the file manufacturing Brammall family built White House and Sheaf House (now a pub), the road leading to the houses became known as Brammall Lane, later shortened to Bramall Lane, and extended across the Porter and would have finished near to where Moor Market is now.

By the 1835 Highways Act, Sheffield Corporation was allowed to replace a wooden bridge with a stone-built structure, and is thought to have been completed by 1845-1846, opening land for development to the south of the town, in places like Highfield, Little Sheffield, and Heeley.

For a long time, it was known as Porter Brook Bridge, and was widened in January 1864, but there were already concerns that the bridge might not be strong enough to carry the traffic that might pass over it. The bridge was now 100metres wide and curved as it followed the course of the river.

This was the height of the Industrial Revolution, and rural land had been swallowed by the town. In 1876, Sheffield’s Medical Officer, F. Griffiths, reported that Porter Brook was full of sewage and the putrid remains of cats and dogs.

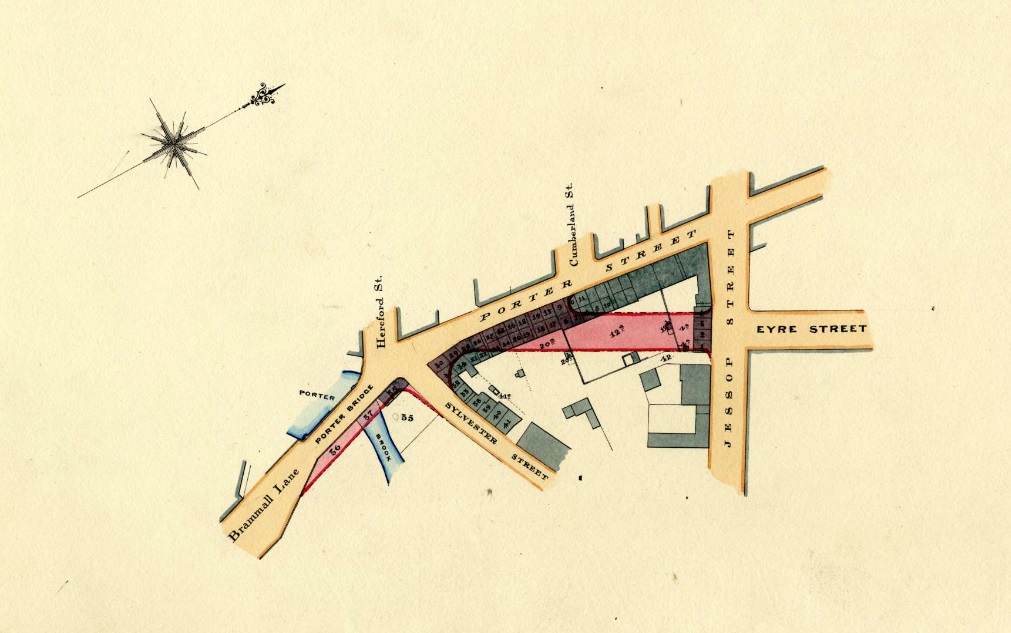

In 1877, the Corporation proposed plans to demolish houses between the west of Eyre Street, and the junction of Hereford Street, Porter Street, and Bramall Lane, allowing the extension of Eyre Street to the Bramall Lane Bridge where roads converged.

Once the roads connected, factories and houses were built, even on the bridge itself, but these have long disappeared, and the modern landscape is quite different.

These days, the only visible signs of the bridge are near Staples car park because the other end remains hidden, and most people are oblivious that Eyre Street runs directly over it.

Halfway under the bridge is the well preserved tail goit from the old Vulcan Works (Staples site) that joins the riverbank and has yielded finds such as a Victorian inhaler and oyster shells.

There is also a visible join in the structure about 25metres from the Decathlon end (75metres from the Staples end) that is thought to be the 1864 extension, while the Porter was culverted further from the Decathlon end of the bridge from the 1890s onwards.

Bramall Lane Bridge has stood the test of time, unlike the later culverted section that famously collapsed, forcing part of the Decathlon carpark to remain closed.

The Staples car park is now fenced off and the skateboarders have gone. This week Lidl announced that a revised planning application is pending, and it might include deculverting of another stretch of Porter Brook.

©2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.