John Henry Andrew sat in the lounge of the steamship Montana feeling pleased with himself. He sipped his Old Forester bourbon and lit the cigar that he’d been given in New York. He was no stranger to travelling and calculated that this had been his thirtieth transatlantic trip.

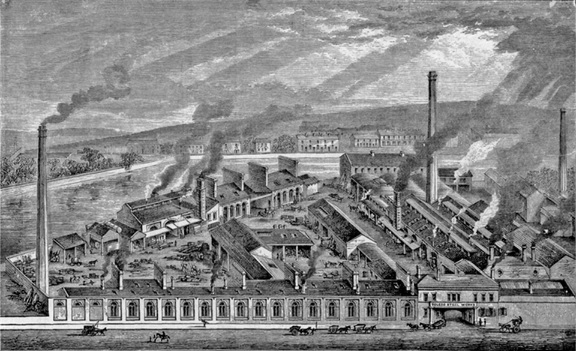

He’d soon be back in Sheffield and would be able to tell his directors at the Toledo Works that he’d secured an important contract. It was a lucrative deal, supplying steel to Joseph Lloyd Haigh, a New York importer, and wire rope manufacturer, based at Brooklyn Wire Mills. More importantly, the steel would be used in the construction of the new bridge that would span the East River from Brooklyn.

Haigh had already taken a sample of steel from J. H. Henry and Company, drawing the rolled crucible steel rods into wire, and had presented a sample of it to the Brooklyn Bridge Company in 1876.

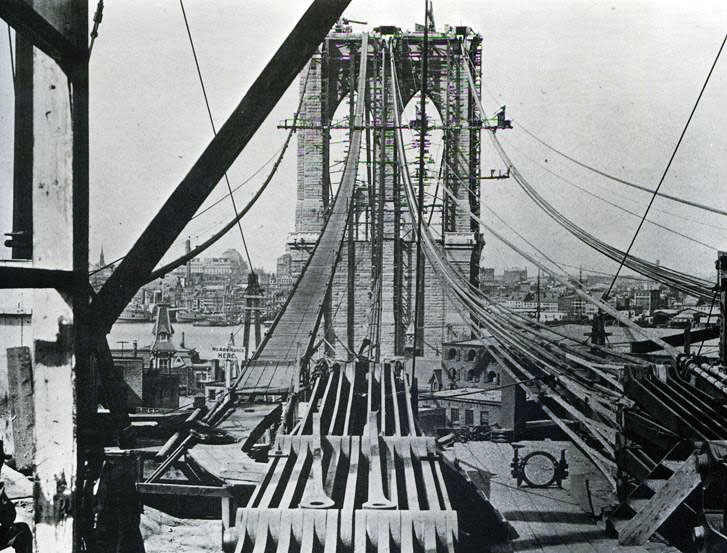

The ropes would be used to support the 486metre bridge, making it the longest in the world, and the sample had been enough to sway the directors that the Brooklyn Wire Mills was the ideal company to manufacture it. Haigh had beaten seven other companies for the contract, including one owned by the bridge’s architect, John Augustus Roebling.

Had John Henry Andrew known what lay ahead, then he might not have felt so pleased on that Atlantic crossing.

This had meant to be a positive post about the Brooklyn Bridge and the myth that it was constructed between 1869-1883 using Sheffield steel. Instead, this turned out to be an intriguing story of deceit, forgery, and monetary loss for the city’s steel manufacturers.

It was anticipated that English steel would be used in the Brooklyn Bridge’s construction, and the submitted bids came in cheaper than their American counterparts. However, the American steel companies put pressure on the US Treasury to increase import tariffs, effectively shutting down foreign competition.

A New York representative from the Sheffield Independent visited the Brooklyn Wire Mills in 1877 and found that only a small portion of steel for the four main cables had been supplied by Sheffield firms.

Haigh had reneged on his promise to J.H. Andrew, as well as the Hallamshire Steel and File Company, and had turned to Anderson and Parsevant of Pittsburgh to supply it instead.

Worse was to come.

Haigh struggled to meet deadlines for the wire rope, and this may have been the reason why he turned to deception to fulfil the contract.

In 1878, the Brooklyn Bridge Company discovered that Haigh had been supplying defective wire. Out of eighty rings evaluated, only five met standards, and it was estimated that Haigh had pocketed $300,000 from his dishonesty.

John Augustus Roebling thought that as much as 221 tons of rejected wire had been spun into cables and used, and so he demanded that another 150 wires were added to each cable as an additional safety factor. Had this not been detected, the consequences might have been catastrophic, and the sub-standard wires remain in place even today.

The Brooklyn Bridge Company decided to keep its discovery a secret and demanded that Haigh supply the extra high quality wire free-of-charge, but this led to his financial ruin.

Two years later, Haigh’s business failed, still owing approximately $20,000 to Sheffield companies, part of this for the Brooklyn Bridge, a figure that was never recovered.

Months later, Haigh was discovered to be a forger and had contributed to the collapse of America’s Grocer’s Bank, an action that led to his imprisonment in Sing Sing.

And so, we find out that the Brooklyn Bridge only has a small amount of Sheffield steel in its structure.

There is also another myth to dispel.

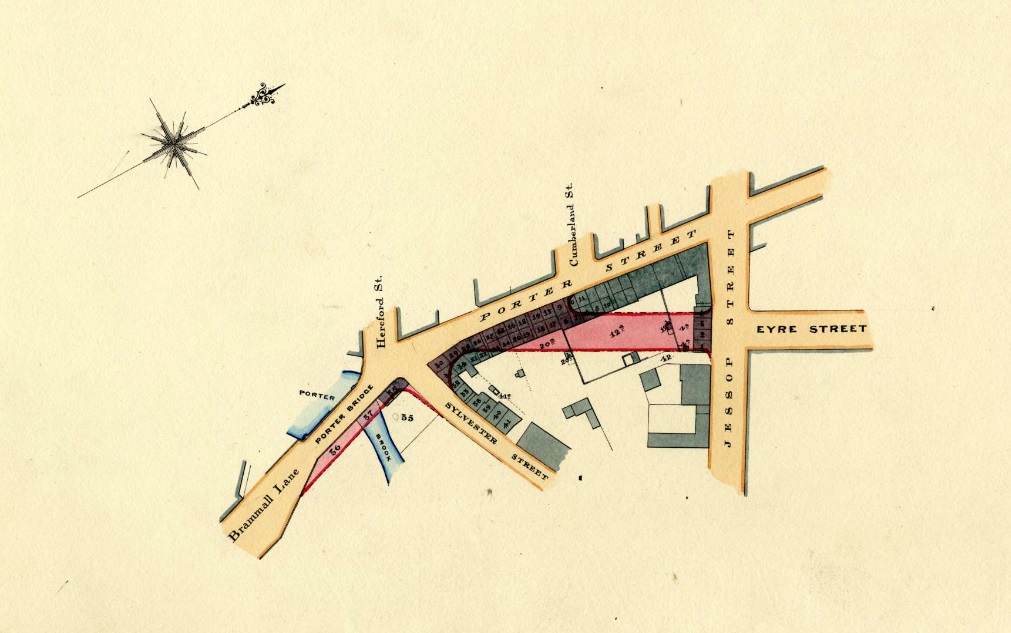

There are suggestions that Brooklyn Works at Kelham Island, once occupied by Alfred Beckett, saw maker, was named after the Brooklyn Bridge because steel from here was used.

We find that Beckett’s home was at Brook Hill, and he acquired his works in 1859 calling them Brooklyn Works, way before work on the bridge had ever started.

NOTE:-

J.H. Andrew and Company subsequently became Andrews Toledo, based at Toledo Works in Neepsend.

©2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.