This post was planned as a tribute to one of Sheffield’s most famous shops, Wilson Peck, but research into its origins have proved to be rather complex. That post is imminent, but during the investigation some fascinating facts emerged about one of the buildings that it once occupied.

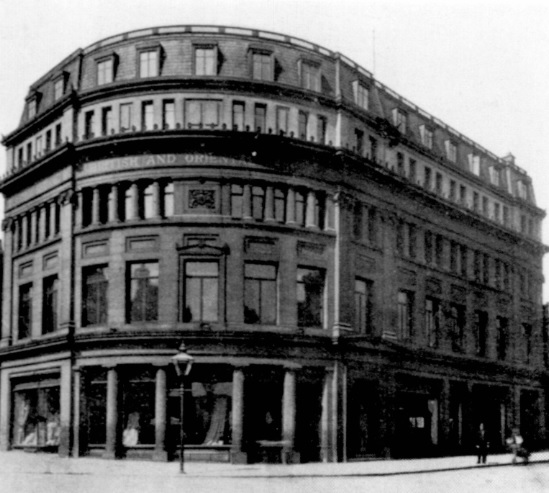

I’m talking about Town Hall Chambers that sits at the corner of Pinstone Street and Barker’s Pool, and now home to the city centre’s last surviving Barclays Bank.

According to Pevsner, it is a ‘worthy, but slightly dull five-storey block of shops and offices’, and like nearby Yorkshire House (another home of Wilson Peck), it has never been listed by Historic England.

The building was designed by Sheffield architect John Brightmore Mitchell-Withers in 1882-85 as part of the street improvement scheme that reinvented Pinstone Lane, a salubrious and narrow thoroughfare, into Pinstone Street, long recognised as one of the city’s most prominent streets.

The site had been an old hostelry called the Norfolk Hotel that was demolished in 1881 as part of the street widening programme. Evidence suggests that J.B. Mitchell-Withers bought the plot of land to build upon, and now I’ve discovered that it was built as a hotel.

In 1884, newspapers advertised that the New Scarborough Hotel was available to let, containing a dining room, commercial room, smoke room, billiard room, refreshments bar and forty bedrooms. It also boasted the best modern appliances for cooking, hydraulic and other lifts, and electric bells.

The following year, it was announced that Lewis’s had ‘acquired the important block of buildings at the corner of Pinstone Street and Barker’s Pool, known as the Scarborough Hotel, and shops below,’ suggesting that the hotel never opened after failing to attract any interested parties.

The name of Lewis’s is famous in the history of UK department stores and the fact that it once had a branch in Sheffield comes as a bit of a surprise.

The first Lewis’s store was opened in 1856 in Liverpool by entrepreneur David Lewis, as a men’s and boys’ clothing store, mostly manufacturing his own stock. In 1864, Lewis’s branched out into women’s clothing, later expanding all its departments, and his motto was ‘Friends of the People’.

The first Lewis’s outside Liverpool opened in Manchester in 1877 followed by Birmingham in 1885. However, it was the Manchester store that it was best known for and later included a full scale ballroom on the fifth floor, which was also used for exhibitions. Its fourth store was in Sheffield, but with stiff local competition from John Atkinson and Cole Brothers, it proved unprofitable, and closed in 1888.

Negotiations quickly took place between the trustees of David Lewis and Joseph Hepworth and Son, a suit manufacturer that had rapidly expanded with over sixty shops across the country.

The premises underwent extensive alterations to accommodate its ready-made clothing, hats, and outfitting departments. The entire building was redecorated and lit with electric lamps, and when plans were submitted for Sheffield Town Hall in 1890, it was proudly referenced as the Hepworth’s Building.

Hepworth’s stay lasted four years, and in 1892 Arthur Wilson, Peck and Co, announced that they were vacating their three premises in Church Street, West Street, and Fargate, and consolidating business in the Hepworth’s Building.

It became known as Beethoven House and lasted until 1905 when it moved to the opposite corner in premises vacated by cabinet makers Appleyards and Johnson, and now known as Yorkshire House.

At which point the building became known as Town Hall Chambers is uncertain, but by the 1930s, the ground floor had been subdivided into smaller shops, and the floors above converted into offices for numerous insurance companies.

Our generations will remember it as a centrepiece shoe shop for Timpson’s and as a short-lived branch of Gap, before being reinvented as a futuristic Barclays Bank. I’d be grateful if anyone can name any other businesses that might have been located here.

And so, we’ve discovered that Town Hall Chambers started as an ill-fated hotel. The building itself survived two World Wars and managed to escape Heart of the City redevelopment, but the irony is that neighbouring Victorian buildings further along Pinstone Street, also built as part of the 1880s street widening scheme, will soon become the Radisson Blu Hotel.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.