gateway building to the city and campus. This requires a

building facade that is both civic but restrained in its nature. (BDP)

News of a significant proposed development within Sheffield’s Cultural Industries Quarter Conservation Area.

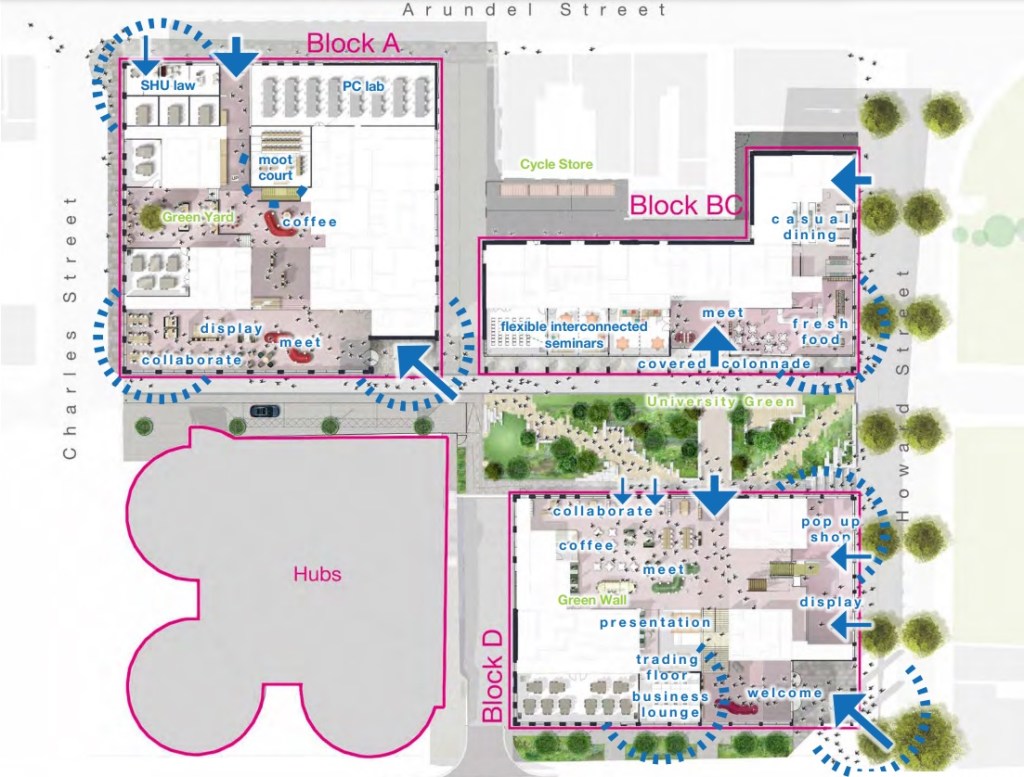

Sheffield Hallam University has submitted a planning application for the erection of three new higher education blocks within its city campus on the existing Science Park site and adjacent surface car park. Blocks A, BC and D are planned around a new public green space provisionally named University Green. It forms a revised Phase One of SHU’s campus masterplan, initiated in 2017/18, and considers changes to the workplace because of the pandemic.

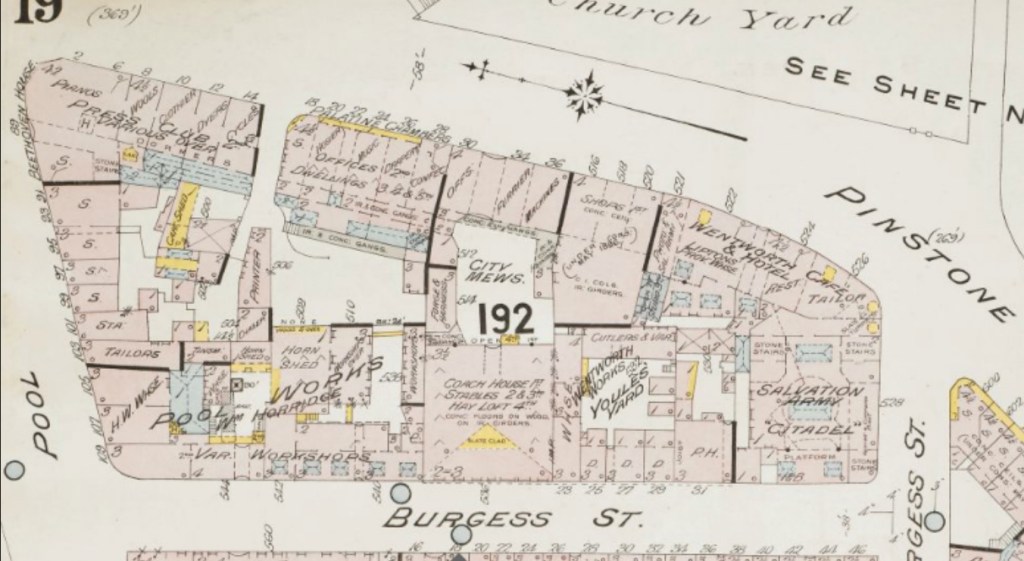

The site covers an area bordered by Paternoster Row, Howard Street, Arundel Street and Charles Street, and is alongside the Hubs complex.

key internal spaces, range of activities and location of key

green spaces (internal yards and University Green). (BDP)

Block D will become a key civic gateway building to the city and campus. In response to this, the tallest part of the development is located at the key junction between Howard Street and Paternoster Row to symbolise a new gateway and reference to the old clock tower of the Arthur Davy & Sons building that once stood on part of the site.

masses that step down from University Green towards the

Globe Pub. (BDP)

Arundel Street where applied learning functions such as SHU

Law may be showcased. (BDP)

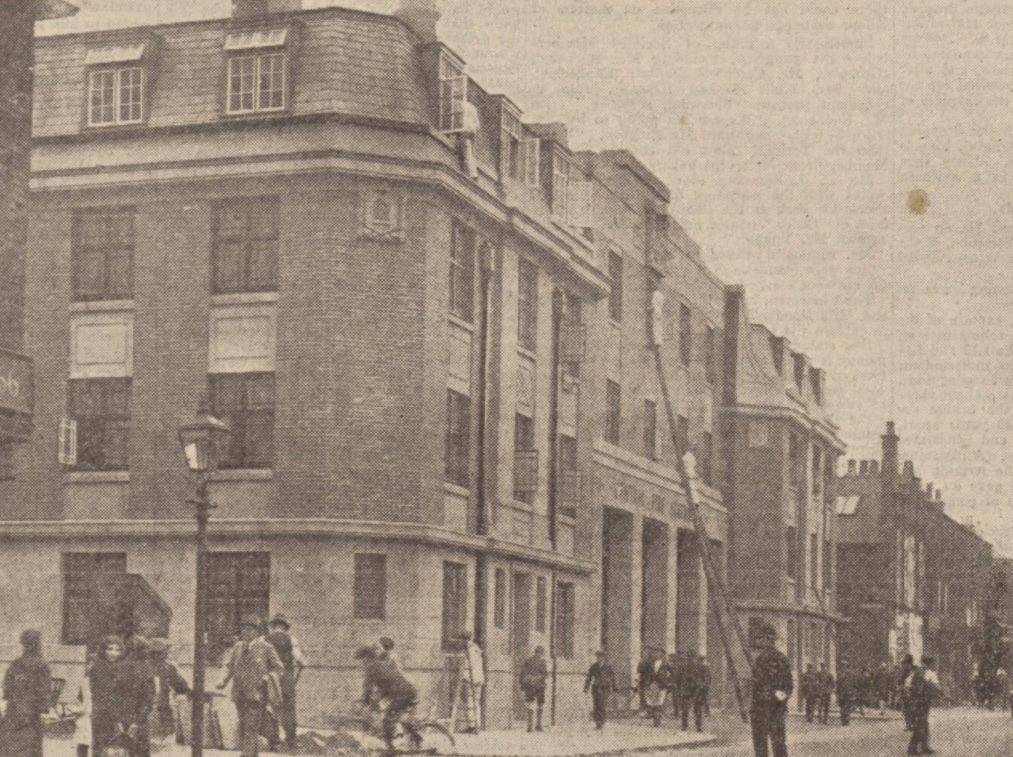

This area was once known as Alsop Fields where ancient hunting rights were claimed. In the late 18th century, the Duke of Norfolk set about his ambitious and grand plan to develop the neighbourhood into a fashionable residential district in response to the growing wealth of manufacture. The masterplan was prepared by James Paine. He proposed a rigid grid framework incorporating a hierarchy of streets, with main streets and a pattern of smaller ones for each urban block, serving mews to the rear of the main houses.

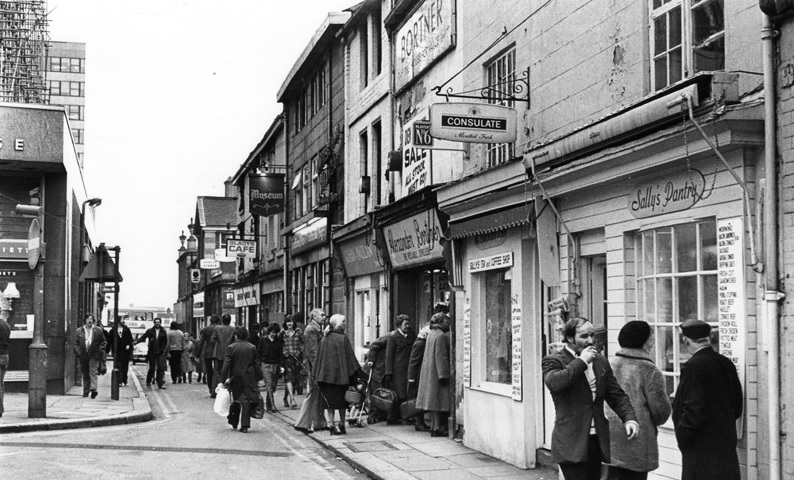

In the 1780s, work on the Georgian estate grid commenced to the north of the site beginning with the parallel routes of Union Street, Eyre Street and Arundel Street from the town centre, extending to Matilda Street (formerly Duke Street). However, the masterplan didn’t transpire largely because Sheffield’s inhabitants didn’t want or couldn’t afford the properties as planned.

Despite the masterplan never being wholly built, the legacy of the Duke of Norfolk is retained in many of the streets being named after his family members.

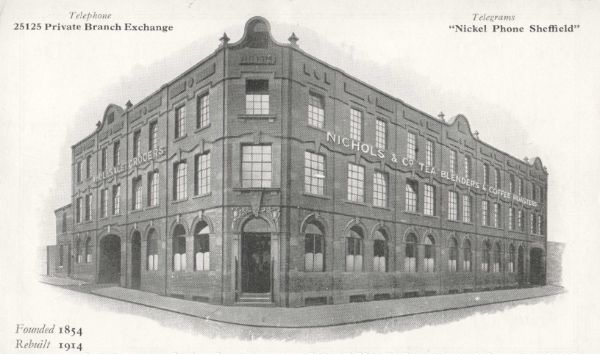

The site designated for redevelopment became a series of factories, workshops, small shops, as well as the site of the County Hotel. Much of the land was cleared during the 1980s, with the creation of Sheffield Hallam University’s Science Park (1996) in red brick by Hadfield Cawkwell Davidson. This will be swept away in the proposed development.

Campus plan Principles that are embedded in the design of

blocks A, BC, D and University Green. (BDP)

© 2021 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.