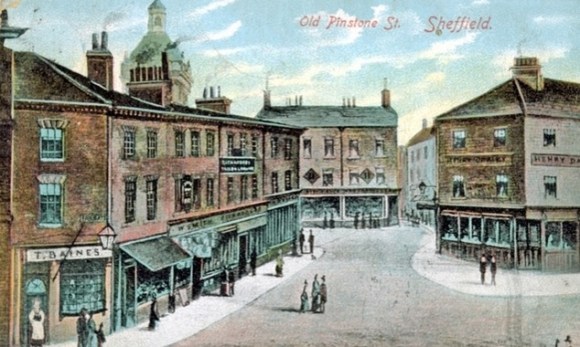

Fargate is in a bit of a mess as it moves away from traditional retail space towards a leisure and social hub. If we’re being honest, we all expect Marks & Spencer to announce the closure of its store at some stage, and what a devastating blow that will be. But there is another retailer that might have a wobbly time ahead. I’m referring to WH Smith whose city centre store opened in the 1970s and is only the second retailer to have occupied 38-40 Fargate. It was, of course, built for provisions merchant Alfred Davy in 1881-1882 by Sheffield architect John Dodsley Webster. Look closely at the exterior and you can still see the carved stone heads of a sheep, cow, pig, and ox.

All is not well at WH Smith, and its High Street stores are struggling to cope with life in the twenty first century. Last month, WH Smith reported another year-on-year dip in sales at its large stores. This contrasts with an eight per cent rise in revenue at its travel stores, those situated in airports and railway stations across the world. “The transformation of the business to a one-stop-shop for travel essentials is delivering strong results, increasing average transaction values and returns,” says the company.

It is a case of things going full circle as I shall explain in a moment, but the question remains. How long will it be before WH Smith calls time on its High Street operation? Sales of newspapers, magazines, books, and stationary, have been eroded by the internet, resulting in a watered-down offer. Instead, we’re left with too many phone chargers and fridges full of chilled drinks. The result is a store lacking atmosphere and too few staff to make the shops look as nice as they used to.

The WH Smith archive is held at the University of Reading but the exact date when it was founded is uncertain. The best guess is sometime between 1787 and 1792 but we do know that its roots were in the newspaper distribution business.

Records show that Henry Walton Smith (1738-1792) to be owner of a Mayfair ‘paper round’ in 1792, delivering expensive newspapers to rich London clients. This was also the year of his death, and the year of William Henry Smith’s birth. Anna Easthaugh, Henry Walton’s widow, ran the business until her death in 1816.

It was her second son, William Henry (1792-1865), who turned it into ‘a house… without its equal in the world’, as The Bookseller described it in its obituary. He had exploited the market for London papers that existed outside the capital, using the newly developed network of seven hundred daytime stagecoaches to get newspapers to the provinces many hours before traditional carriers, the night-time mail coaches. There was little profit in the operation, and it took him thirty years to realise that he needed help, and a successor.

His son, William Henry II (1825-1891), had wanted to be a clergyman, but his father demanded that he join the business instead. It was a shrewd move, because William Henry II capitalised on the new railway network as a speedier alternative to the coach, and then he started bookstalls, and developed the more familiar role that the company became famous for. By the end of the century, there was a WHS bookstall on almost every station (in 1902, there were 1,242 of them).

Writing about the history of WH Smith in 1985, Michael Pountney said that “expansion seemed unstoppable. Extension of the railway network meant more stations. Elimination of stamp duty on newspapers meant lower prices and more sales. Better education meant more readers. Unstoppable, but not inevitable: Smith’s got the business because they were better at it than their competitors, more reliable, more efficient, better able than their less scrupulous rivals to do good business without offending against the stern moral values of the age.”

Things were about to change.

Before the end of the nineteenth century, railway expansion slowed almost to a halt, the Victorian boom slowed, and William Henry had become an MP that took him away from the business. He died in 1891, leaving the business floundering.

The merger of two of the biggest railway companies, GWR and the LNWR, in 1905, resulted in WHS losing 250 bookstalls at its stations, but it responded by opening 144 shops in towns where they had lost a stall. The man credited for this entrepreneurial genius was CH St J Hornby, friend of WHS’s new proprietor, William Frederick Danvers Smith (later second Viscount Hambleden).

Opening shops was a retaliatory measure against the loss of the bookstall contracts, but its move onto the High Street was a success, with rapid extension across most of the country in the twentieth century, matched by a reduction in the importance of bookstalls. Only with the full development of the shops did the stationary, book and record departments come to rival the supremacy of news and periodicals.

WH Smith went public in 1949 but continued to be run by the Smith family until 1972 when David Smith stepped down as chairman, and then Julian Smith’s retirement in 1992 marked the end of family involvement in executive management.

In 1966, WH Smith created a standard book number consisting of a nine-digit code, which was adopted in 1970 as the international standard number and finally became the International Book Number (ISBN) in 1974.

Let us not forget the other enterprises that WH Smith were once involved with. WH Smith Travel operated from 1973 to 1991, and in 1979 it acquired the Do It All chain of DIY stores, later merging with Payless DIY (owned by Boots). It went on to purchase 75 per cent of share in Our Price music stores and even held a minority stake in ITV. Between 1989 to 1998, the company was a major stakeholder in the Waterstones bookshops, resulting in WHS own bookshop brand Sherratt and Hughes (which had already subsumed Bowes & Bowes) being merged into Waterstones. WHS eventually pulled out of all its external interests.

And so, we come that full circle. The High Street shops are struggling, victim of changing shopping trends, and the future of the company appears most likely to be catering to the needs of travellers, over 640 stores in thirty countries outside the UK, much like those Victorian bookstalls did.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.