A long time ago, I read a book containing John Gielgud’s letters and I seemed to remember that he called the people of Sheffield ‘peasants’. After that, I didn’t fancy watching his films anymore. Gielgud (1904-2000) was born in South Kensington, and as an actor and theatre director, he looked down on us poor northerners.

I recently came across a copy of the book in a second-hand bookshop and couldn’t resist flicking through to find that discriminatory paragraph again. It turns out that I did him a disservice, because he didn’t call us peasants after all, but certainly didn’t like Sheffield.

“This is an appalling place and just as I remembered it before – awful slums and poverty everywhere and the audiences sparse and unresponsive.”

He wrote these brusque words in a letter to his mother in October 1927, and even though he was probably right, I’ve never liked John Gielgud since.

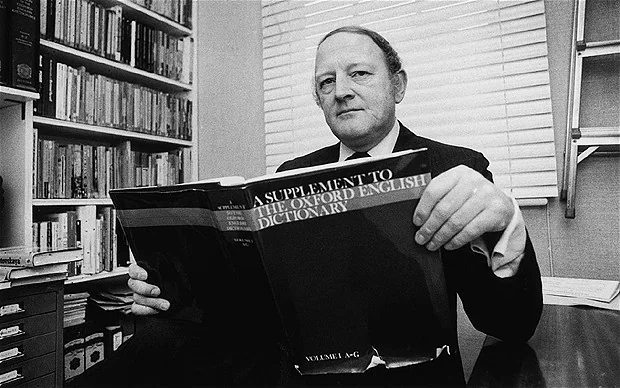

The same feeling came across me when I read ‘Skip All That’ – the memoirs of Robert Robinson that was published in 1996.

Robinson (1927-2011) was an English radio and television presenter, game show host, journalist and author. He presented Ask the Family for many years on the BBC. I was surprised to learn that in his younger days he worked as a journalist on the Weekly Telegraph, a satellite of the Sheffield Telegraph.

But his memoirs show that he regarded his stint on the Telegraph as a low point in his career. At that time, the Sheffield Telegraph was owned by Kemsley Newspapers, which also had The Sunday Times, The Daily Sketch and The Sunday Graphic amongst its titles.

“The Editorial Director explained the Weekly Telegraph was about to be relaunched as a big-time glossy and advertised on the eye-pieces of buses. I was to add my champagne to the editor’s brandy. A combination of which turned out to be more or less Tizer.

“The woebegone mag was printed on thin blotting paper and sold for threepence to readers I imagined to be comprehensively deprived. Nothing in the Kemsley’s frowzy empire looked capable of anything but lining a cat litter, and shortly after I started forging the (readers’) letters no more was heard about advertising or glossiness. And it wasn’t even Fleet Street, it was only Gray’s Inn Road. Kemsley House was a heap of red brick in the wastes between Clerkenwell and King’s Cross, and had the dejected air of a building site where the money had run out.

“I wondered why they didn’t invite me to write a column for the leader page of the Sunday Times, and what I hacked out on two fingers filled the Weekly Telegraph to overflowing.

“We published in London, but I was allowed an occasional jaunt to Sheffield to see how they printed the thing. Behold, on one such trip I saw a man on the platform who actually held a copy of the magazine in his hand. I approached him: was he, I importantly enquired, a regular subscriber? Not really, he replied. And why was that, I asked, giving him to understand that on matters of policy, a word from me and the thing was done. ‘It’s a bit too instrooctional;.’ he said. I simply thought he’d caught a whiff of the intellectual seasoning I was adding to the mix. ‘Listen,’ I said, ‘we’re trying to get intelligent people like you to come up-market with us.’ ‘Then where are the pictures of scantily-clad women in bathing costumes?’ he asked. ‘And the crossword’s got too many big words.’ It wasn’t the length of the words, it was the necessity of having second sight. The crossword prize was a guinea, and the puzzle was rigged.

“Provincial papers are second division, but the Kemsley lot were second rate as well, the issue on sale any day in Sheffield, Manchester or Newcastle as stale in spirit as if it had been pulled from the musty files in the cuttings library.

“The pilotless hulk went down stern first, and clinging to a spar I was hauled aboard a ghost ship called the Sunday Graphic.”

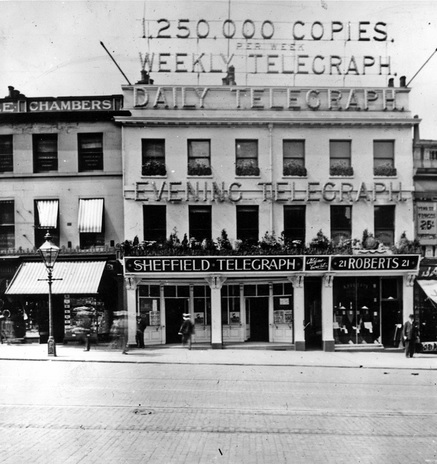

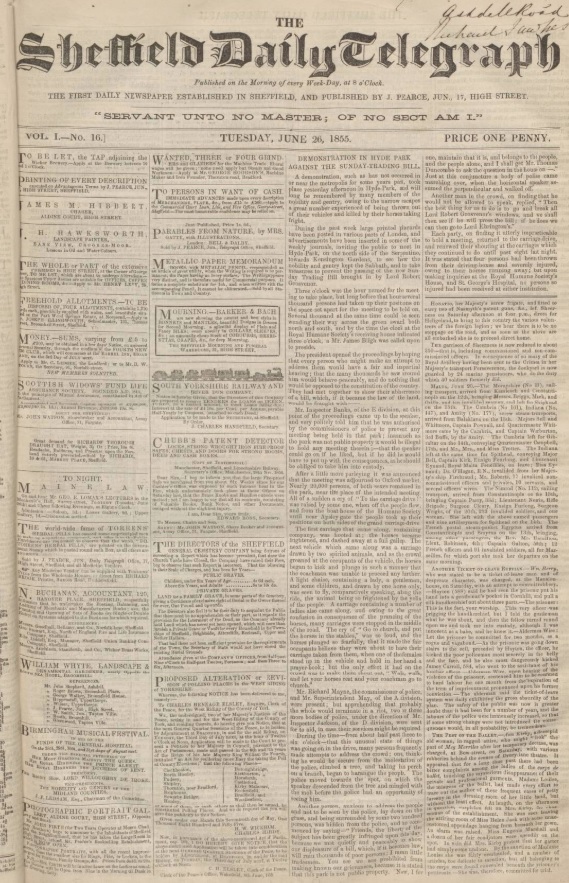

Founded in 1855 as the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, it became known as the Sheffield Telegraph in 1938, and its sister, The Star, continues as a poor ancestor.

I must admit that Robinson was an excellent writer, and he did get his wish to write the Atticus column in The Sunday Times, as well as becoming one of the presenters on Radio Four’s Today programme. But when you read his work now, there is that niggling belief that he looked down on those of us who lived and worked outside London, even though he was born in Liverpool.

And so, as far as I am concerned, Robinson is shunted into the same cupboard as John Gielgud, and his book is on its way to a charity shop.

What would Robinson think about provincial newspapers now?

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.