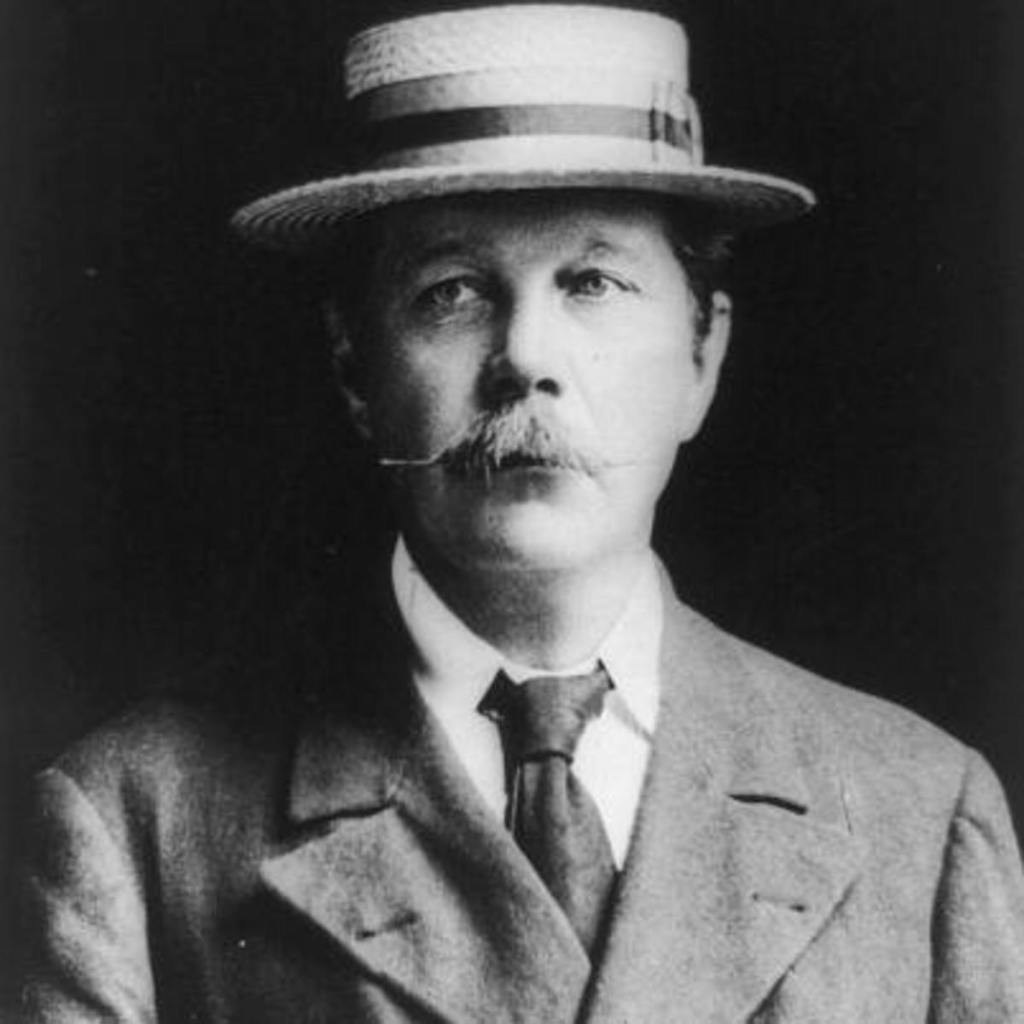

Sherlock Holmes remains the most popular fictional detective in history. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) is best known for the 60 stories he wrote about Sherlock Holmes, but he was also a physician and spiritualist.

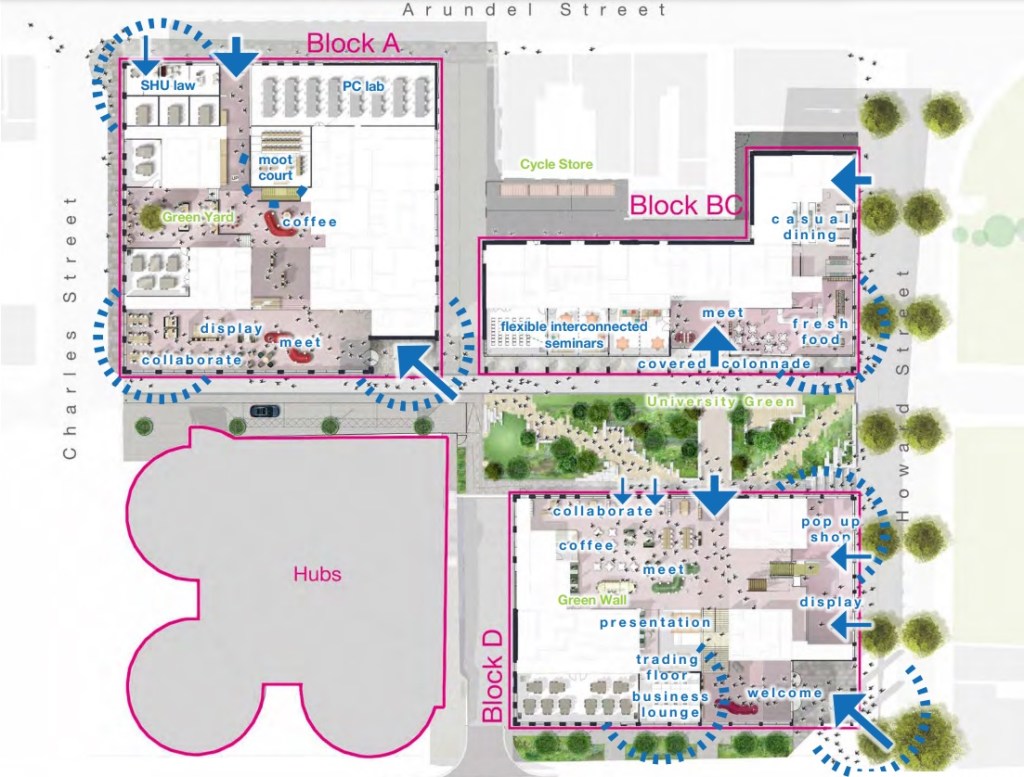

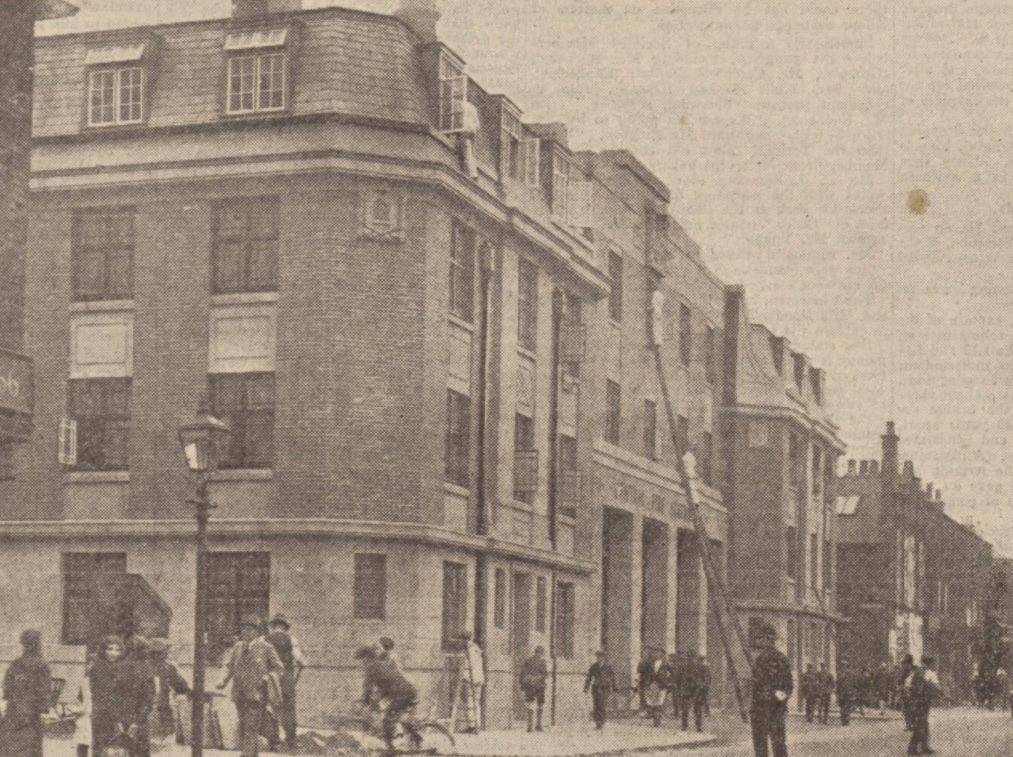

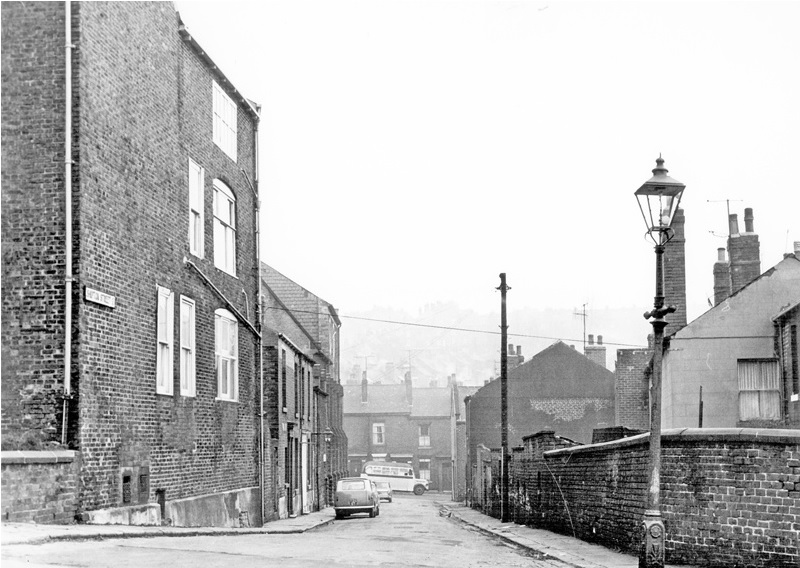

In November 1921, Conan Doyle gave a lecture at the Victoria Hall. It was arranged by the Sheffield Educational Settlement and the title was “Modern Psychic Thought.” He had arrived the day before and at once proceeded to the Sheffield Settlement’s premises, in Shipton Street, Upperthorpe, where an informal gathering had assembled, and where he spent the night.

The Sheffield Settlement had been founded by the YMCA in 1918, opening the following year under the wardenship of Arnold Freeman. Its mission was to create a better society. ‘That which described in three words is Beauty, Truth and Goodness, and described in one word is GOD.”

Conan Doyle was accorded a hearty welcome, and in a brief response expressed his pleasure at seeing a “growing centre of activity.” He said he could imagine how beneficial it was to the city to have in the Settlement such a centre of art and culture of every kind.

Another comment made by Conan Doyle sparked the greatest interest.

“It is not generally known that I once lived in Sheffield. When I was a medical student, 17 or 18 years of age, I advertised my willingness to learn a little about medicine, and a Dr. Richardson, who lived in Spital Hill, was good enough to take me on. I had no salary, which was probably what I was worth, and it was just as well for the population of Sheffield that in a few weeks I got the order of the boot.” (Laughter.)

And it was true, Conan Doyle had come to Sheffield in 1878, working as an assistant to Dr Charles Sydney Richardson at Nelson Terrace, 80 Spital Hill. It was evidently not a happy experience.

“These Sheffielders would rather be poisoned by a man with a beard than saved by a man without one.”

Conan Doyle had, by this time, become an agnostic, and although he already had interest in psychic phenomena, his philosophy was still materialistic.

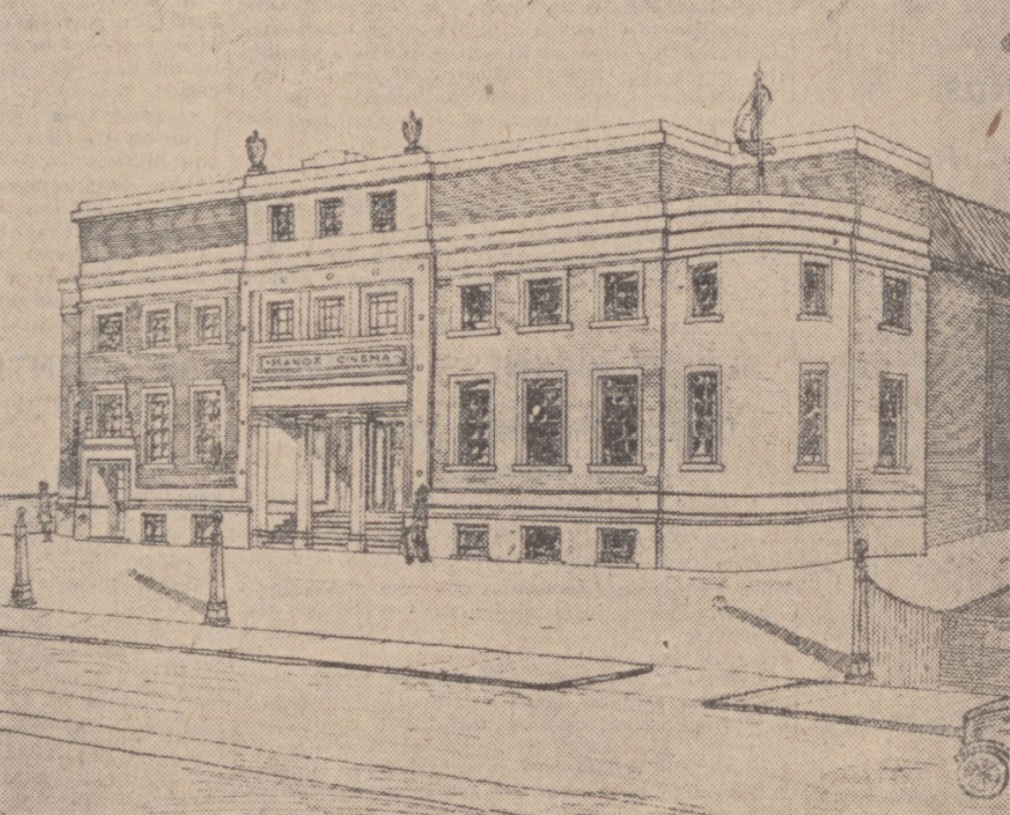

However, at the 1921 lecture the ‘world-famous’ novelist found the Victoria Hall only half full. He related to the ‘jury’, as he called them, that “The subject is by all odds the most important thing in the world. It is a thing which is going to influence and bear upon the future of every man and woman in the room. There is one alternative, and that is either this movement is the greatest delusion the human race has ever experienced, or else it is far the most important thing – the most important addition to our knowledge which has ever come from the centre of all knowledge.

“The afterlife,” he said, “is merely a waiting room where you are waiting, very likely in discomfort, until you are fit to go on.

“Everybody eventually gets to heaven, but these places of waiting – hospitals for the soul they might call them – are not pleasant places to wait in. One of the real punishments is in being earth-bound.”

Conan Doyle related séance experiences and told of a conversation he had with the spirit of James Johnson Morse, a ‘trance medium’ who had died in 1919. The departed leader claimed that their last meeting had been in a newspaper office. “No,” said Conan Doyle, “It had been at Sheffield, at a meeting at the Empire Theatre.” Afterwards, he was reminded by his wife that it had been in a newspaper office.

Almost as soon as the people had left the Victoria Hall, they were handed pamphlets bearing such phrases as ‘Spiritualism is to be avoided like the plague’.

Conan Doyle died nine years later, in July 1930, and a few weeks later the Sheffield Daily Telegraph was one of only a handful of newspapers that printed a ‘spirit’ photograph of him.

The image was vouched by the Rev. Charles Tweedale, Vicar of Weston, near Otley, a man Conan Doyle had known quite well, and who had been confident that the author would manifest himself after death.

In a series of sittings immediately after Conan Doyle’s death, Tweedale claimed to have had communication with him (“Well Tweedale, I have arrived here in Paradise. That is not heaven. Oh, no! But what we should call a dumping place, for we all come here as we pass on to rest.”)

Rev. Tweedale had then sat with the psychic, William Hope, of Crewe, and photographs taken of the séance. Afterwards, four plates were exposed, and two were “clearly recognisable pictures of Conan Doyle.”

The ‘spirit’ photographs of Conan Doyle, although still available if you know where to look, rarely surface these days. Perhaps not surprising considering that William Hope, who had become famous for dozens of other ‘ghost’ pictures, was later found to be a fraud, and had double-exposed his images.

© 2021 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.