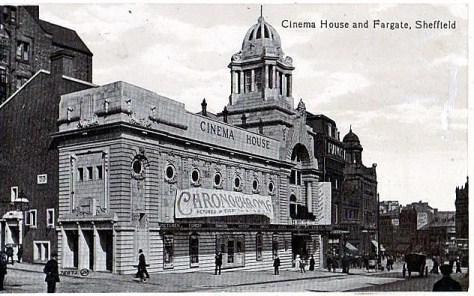

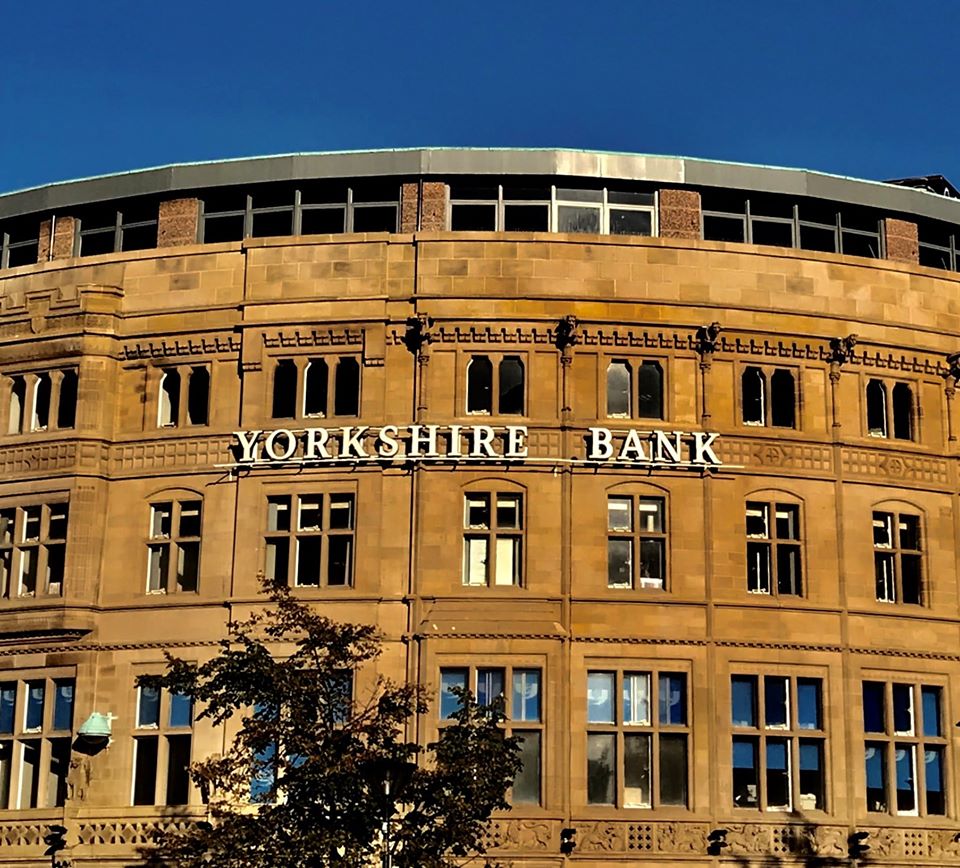

No. 9 has stood at the end of Fargate all our lives. It is the tall, detached building standing between Chapel Walk and Black Swan Walk and is in a sorry state.

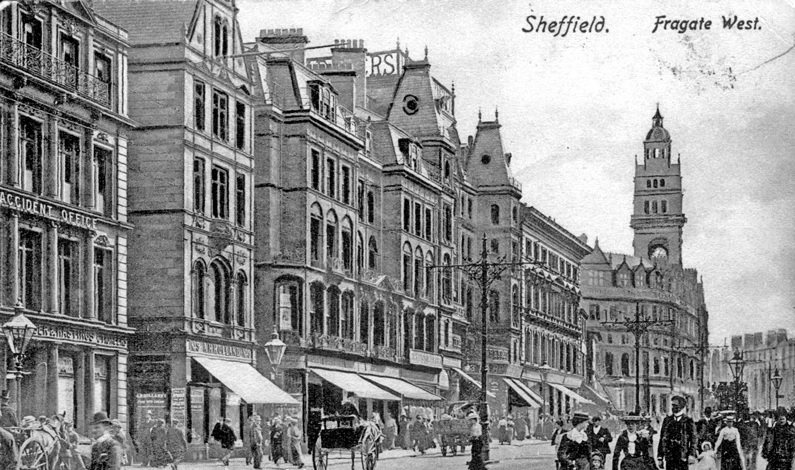

It is hard to imagine that this building was part of the Victorian renaissance of the old town centre, one that marked the widening of Fargate and set the building line for later High Street improvements.

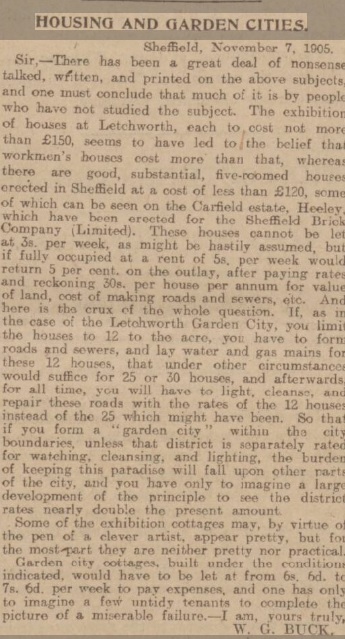

Plans to widen Fargate were proposed in 1875, but it was not until the late 1880s that work started. Old buildings on the east side were flattened extending back from Fargate for distances varying from 60ft to 240ft.

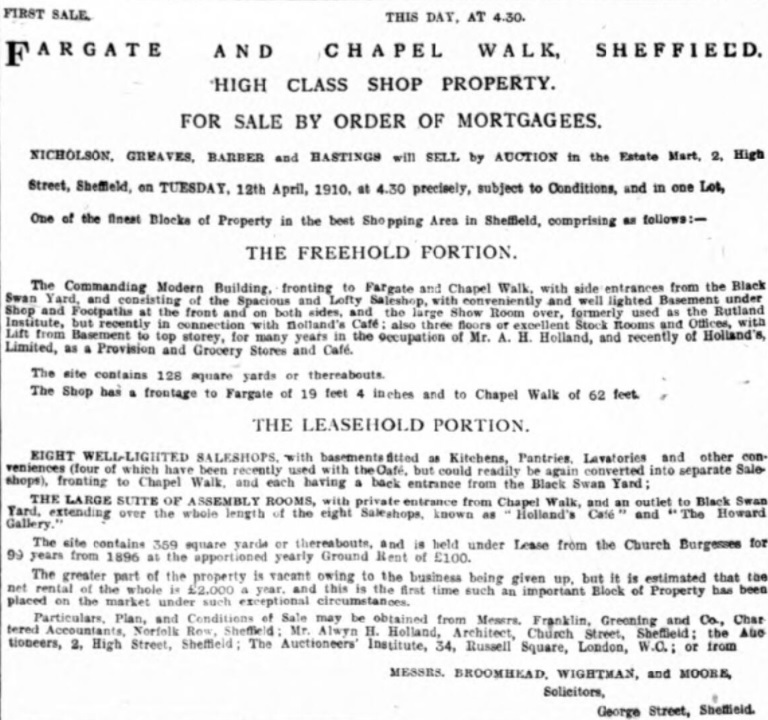

It would appear that Lot 4, a plot of land containing about 150 square yards on the north side of Chapel Walk and south of a foot road (Black Swan Walk), with a frontage of 19ft to Fargate and 72ft to Chapel Walk, had been the site of the Black Swan Public House.

In 1887, Sheffield Corporation paid William Davy, the licensee, £11,160 for the land and demolished the pub.

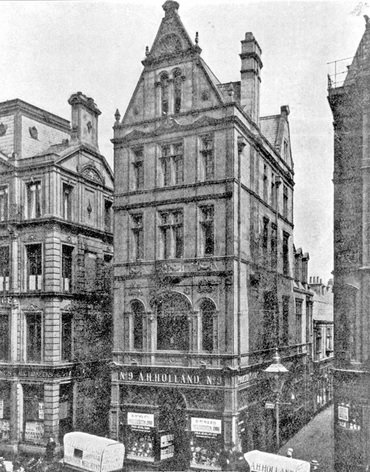

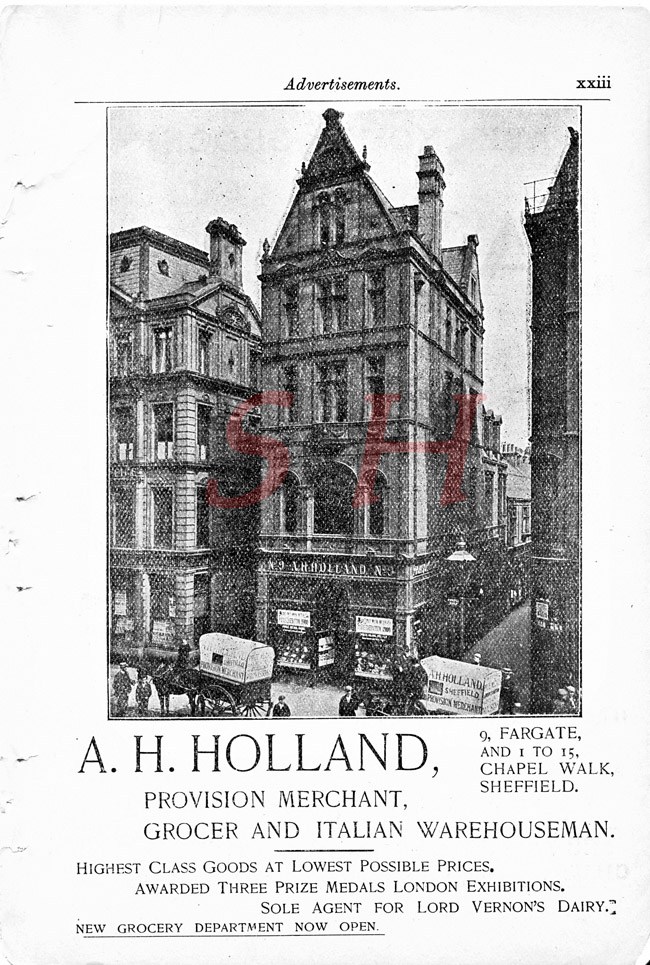

The freehold was bought in 1888 by A.H. Holland, Provisions Merchant, founded in 1844 by Alwin Hibbard Holland, whose previous shop had been at No. 3 Fargate, one of those flattened for street widening.

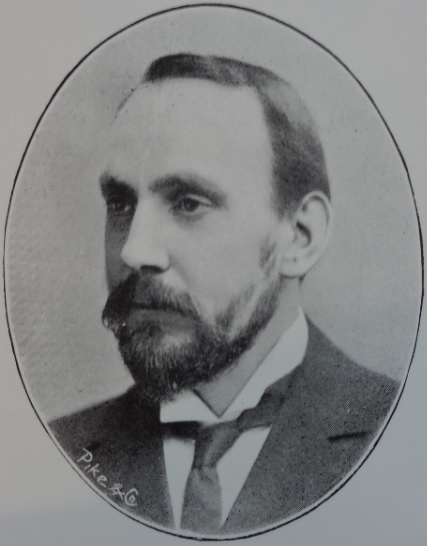

Alwin Hibbard Holland had died in 1883, the business continuing through his wife, Eliza, and youngest son, Alwyn Henry Holland. (His eldest son, Kilburn Alwyn Holland, also had a provisions business, but appeared to have played only a small part in the family business).

Eliza Holland played an important role in the success of A.H. Holland, but it was Alwyn (whose story will be covered in a future post) who established the business in new premises at No. 9 Fargate.

Alwyn had been educated at Brampton Schools, Wath upon Dearne, before becoming a pupil, and afterwards, assistant to Sheffield-architect John Dodsley Webster.

After his father’s death, he joined A.H. Holland which he ran with his co-executors, and co-designed the new premises along with Flockton, Gibbs and Flockton.

Thomas James Flockton had negotiated the purchase of the property and acted for Sheffield Corporation in the resale to Alwyn Holland, a fact that did not go unnoticed to sharp-eyed citizens.

Building work started in early 1889, with Sheffield-builder George Longden and Son chosen for the work, but progress was hampered when bricklayers and labourers went on strike demanding more money.

The new shop was eventually completed and opened to an expectant public on 9 November 1889 selling the ‘highest class goods at the lowest possible prices’. As well as the shopfront on Fargate, the premises extended down Chapel Walk occupying Nos. 1 to 15. The firm was awarded prize medals at the London International Exhibition and the International Dairy Show, sufficient for it to become sole agent for Lord Vernon’s Dairy (from Sudbury Hall in Derbyshire).

In 1891, the Rutland Institution occupied rooms overlooking Fargate above the shop. It was named after the Duchess of Rutland, who opened it, and was formed in connection with the Sheffield Gospel Temperance Union.

As well as being a shopkeeper, Alwyn Holland was a watercolour artist and his work was displayed inside the shop, ‘displaying marked originality both as an architect and an artist’.

It might have been Holland’s aspirations as an artist that ultimately led to the downfall of A.H. Holland.

With a sizeable income the firm built new property on adjoining Chapel Walk, renting out eight shops at ground level with a large suite of assembly rooms upstairs, including the Howard Gallery, for high-class art exhibitions, and Holland’s Restaurant.

The gallery opened in 1898 but proved a failure, closing its doors in 1904. By this time, the Rutland Institution had moved out, and the entire upper floor was extended into rooms above No. 9 Fargate and remodelled as tea rooms.

In 1906, a new company was created, Hollands Ltd, to take over the business carried on by Eliza Holland and Alwyn Henry Holland at No. 9 Fargate and Nos. 1 to 15 Chapel Walk, as well as the restaurant business carried on by Alwyn at 17-23 Chapel Walk (and also at Sheffield University Rectory).

Joining Eliza and Alwyn as directors were Smith William Belton, a provisions merchant from Market Harborough, William Whiteley, a Sheffield scissor manufacturer, Richard P. Greenland, Liverpool soap manufacturer, Arthur Neal, Sheffield solicitor, and George Shuttleworth Greening, accountant.

A second grocery and provisions business were established on Whitham Road at Broomhilll, but despite new investment things did not go particularly well for A.H. Holland, and in 1909 the business slipped into voluntary liquidation.

Net losses since the formation of the new company amounted to £3,826 and directors attributed poor performance to deficient continuity of management, shortness of working capital, and consequent loss of business due to the depression in Sheffield.

The following year the freehold of No. 9 Fargate was offered at auction, as was the leasehold portion on Chapel Walk, once home to the Howard Gallery and Holland’s Café.

By the end of the year, No. 9 Fargate was used as an auction house by Arnold, Prince, Bradshaw and Company, and the following year fell into the hands of Sykes and Rhodes, costumiers and furriers, which remained until 1924.

By this time, the building had suffered from Sheffield’s age-old problem of black soot, darkening the stone, making it rather ‘dull-looking’.

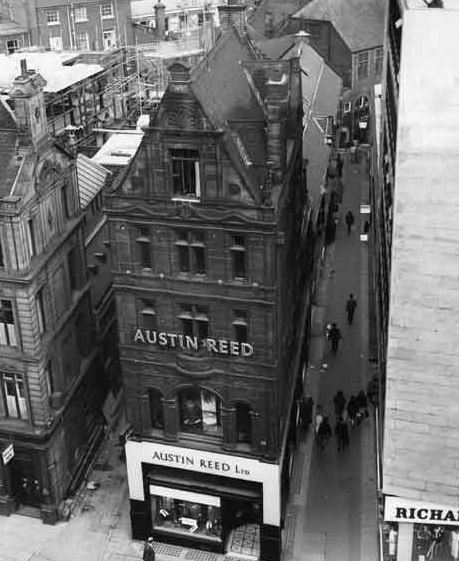

However, the building was about to be reinvented with the opening of a shop in Sheffield by one of Britain’s leading tailors.

“A cynic has remarked that one of the reasons why Austin Reed Ltd have opened a shop in Fargate is because the male members of the community in Sheffield need attention in sartorial details.”

The business had been founded by Austin Leonard Reed (great grandfather of Asos founder Nick Robertson) and claimed to be the first menswear store to bring made-to-measure quality to the ready-to-wear market. Its first store was in London’s Fenchurch Street and by 1924 had branches in all the most important towns and cities of England.

“Time is not so long distant when Sheffield relied on its old-established businesses, handed on from father to son, but, with the passing of the war, there came a change, and today, as quickly as premises can be acquired, firms with world-wide reputations are erecting palatial buildings, limited only by the space at their disposal.”

The company spent a small fortune converting the building, the designs drawn up by P.J. Westwood and Emberton, of Adelphi, London, and involved the original builder, George Longden and Son.

Outside included a beautiful marble front erected by Fenning and Co., Hammersmith, made of Italian Bianco del Mare and Belgian Black Marble. The entrance lobbies contained lines of non-slip carborundum inserted into marble paving.

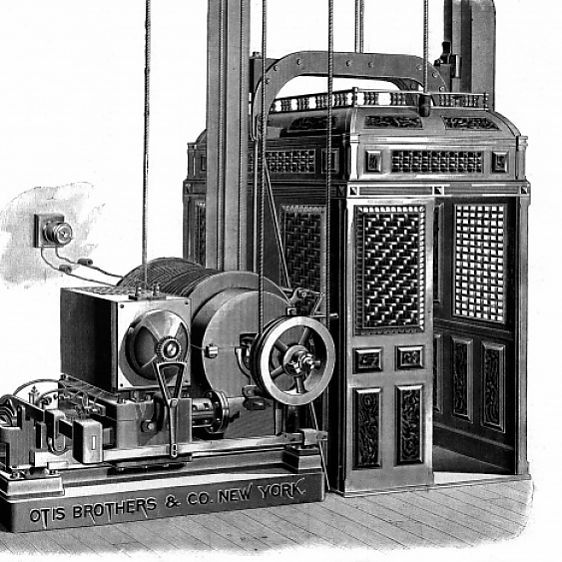

The building consisted of a basement, three sales floors, and an office situated at the top. They were linked by staircases and the lift, a survivor from A.H. Holland days.

The basement was used for dispatching, the ground floor for the tie, collar, and glove department, the first floor was for hats, shirts, and pyjamas, while the second floor formed the ‘new’ tailoring department.

“Inside, everything blends and tones; there is nothing garish to the eye. The ground-work is of oak panelling, staircase, and fittings. On the ground floor, the firm has arranged six windows nicely furnished with parquet beds, the door at the back being glazed with embossed glass to the architect’s design.

“The window lighting – admired by thousands – is worked with x-ray window reflectors, and each window has a special plug for ‘spotlights’ or experimental lighting effects.”

The front of the shop was also illuminated with a ‘Dayanite’ electric sign installed by the Standard Electric Sign Works. This, and the window lighting, was controlled by a revolutionary time switch that allowed them to be switched off on Sundays.

While the outside was impressive, the interior had the latest shop-fittings made of lightly fumed oak, with polished edged frameless mirrors, supplied by George Parnall of Bristol and London.

The coat cabinets worked on an American principle where doors opened and disappeared into the sides of the cabinet, and a large rack, laden with coats on pegs, was drawn out and slowly revolved.

The counters had small reflectors and low-voltage gas-filled lamps, manufactured by G.C. Cuthbert of London, that provided white light and gave a brilliant effect to the goods.

Another innovation was an electric hat cleaner whereby a visiting customer with a hard felt hat could have it cleaned and renovated in three minutes.

Customers were most impressed with Austin Reed’s new payment and receipt system.

When an item was purchased the assistant placed the money, bill and duplicate into a cartridge that was inserted into pneumatic tubes, similar to those used in newspaper offices, that within ‘three second’ had reached the top of the building. The office assistant then placed the receipt and change in the cartridge and the procedure reversed.

Austin Reed also used several local contractors.

Decoration was completed by F. Naylor, of Abbeydale Road, plumbing by George Simpson and Co., from Broomhall Street, electrics by Marsh Bros., of Fargate, and the structural engineers were W.H. Blake and Co., from Queen’s Road.

Austin Reed remained at No. 9 Fargate the 1970s, the building becoming a Salisburys bag shop and subsequently a victim of the relentless ‘chain store shuffle’, its last incumbent being Virgin Media.

As I write, it is a pop-up Christmas store, in darkness due to Covid-19 restrictions, with a sun-tanning parlour above.

© 2020 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.