The sun shines, and a pigeon meanders between the old church gates near Sheffield Cathedral, next to the tram stop where High Street meets Church Street. It pays more attention to the gates than passers-by do, the majority of whom don’t know that they exist. These gates appeared in the nineteenth century and today I must use my imagination.

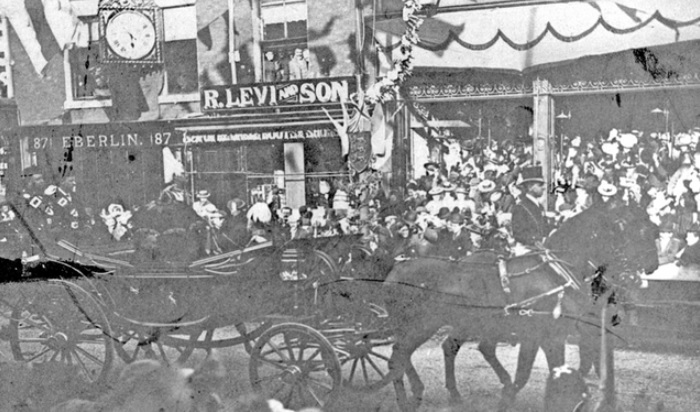

I have gone back to the time when these streets were crowded with pedestrians who had to keep their eyes open, and their wits about them, because they might easily have been run down by a horse and cart or Hackney Carriage. The air is abundant with noise, the clip-clopping of horses, hawkers selling their wares, and shouts of men who have consumed too much ale. Most people are shabbily dressed because they come from poor families, but there are also the gentlemen who wear breeches and stockings, waistcoats and frock coats, linen shirts, buckled shoes, and three-cornered hats. One of them carries a walking cane and pauses to read something that has caught his eye in the Sheffield Register. .

I am outside the Town Hall, built to the points of the compass in 1700, and which partly lies within the graveyard of Sheffield Parish Church and out into Church Lane. The man with the newspaper notices and walks over.

“What are you looking at?” he asks curiously. “I believe I am looking at Sheffield’s first Town Hall,” I reply. “Nay lad. That’s where you’re wrong. Let me tell you that there was one before this, up yonder, in a house near the Townhead Cross. It was a house converted for town affairs, and in its cellars were chains to keep hold of the misplaced souls of this parish. They built this one at the turn of the century to replace it.” The man looks at it and sighs. “It’s a miserable place. When the street was widened, I would have expected this building to be taken down, but it still stands as a disgrace to Sheffield.”

The stranger identifies himself as William Hollingworth, a solicitor on Norfolk Row, and he is right. The building is not grand like Town Hall’s should be, it is far too small, and built of plain brick with iron palisaded windows. Its northeast corner is separated by a narrow space from the southwest corner of Mr Heaton’s shop. Across this space, that I know as East Parade, the Church Gates have been placed diagonally. The long east front looks down High Street; the southeast corner and the short south side project into Church Lane, while the west and north sides are entirely in the church yard.

Hollingworth pointed his cane at the roof. “The only redeeming feature is the belfry, with its gilded ball, and the bell that is only rung on important occasions.”

He guided me up a flight of steps and stopped. “There is talk that we might build a new Town Hall over at Barker’s Pool, but that is too far away. My own preference would be to build one in the historic town, perhaps Waingate or Old Haymarket.” “What was here before?” “Nowt, as far as I know, but there used to be a well hereabouts, and that would have been filled in when they dug out the foundations.”

Hollingworth reached into his pocket and pulled out a large brass key to open the wooden door. He guided me into an ante room and closed the door behind him. Above us, far too high to reach, were leather buckets sat on shelves. “You’ll find similar ones in the church,” he said. He rested his cane against the wall, reached for a long pike and lifted one of them down. “Do you know what these are?” I had no idea. “Mr Rollynson made them. Before we had the town fire engine these buckets were used to fight fires. I’m afraid that they were no use because flames worked quicker than any man could.”

The door ahead was ajar and creaked as he pushed against it, opening into one large room, plain in décor, lined with rickety chairs, and a long mahogany table covered in green baize at its centre. The floor was covered with braided matting, well-worn, and fraying at the edges. It was gloomy, the windows struggling to let in enough light, with curtains, urgently in need of fresh dye, hanging either side. A candlestick was suspended from the ceiling, the candle long extinguished and a flow of cold wax could be seen. “This can be a jolly room. On special occasions we set tallow candles in clay and put them in each window.”

At the opposite end of the room, raised on a platform, was an impressive chair with a coat of arms fixed to the wall above it. Hollingworth noticed my interest. “That is the Royal Arms,” he said. “James Truelove did the iron work and Jonathan Rutter gilded and painted them.”

I sat in the chair that was hard and uncomfortable but suggested that somebody important might sit here.

“When it first opened, the Trustees said that the Town Hall could only be used by the town’s Burgesses to meet and consider the Collector’s accounts and keeping of the Courts of the Lord of the Manor.” Hollingworth laughed. “That didn’t last long because Yorkshiremen have regard for money. The temptation was irresistible. Before long, it was let to stage players, to Richard Smith, the bookseller and dancing expert, who rented it for weeks, to all kinds of showmen, and is popular for auctions. Now, the West Riding Sessions are held here every two years, and the magistrates sit in Petty Sessions once a week.”

“What is in that big chest under the window?”

Hollingworth tapped the chest with his walking cane. It was padlocked. “This is the ‘Town’s Chest’,” he said. “Inside is the true copy of the Town’s Burgesses’ grant to Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, for him, his heirs, and successors, and the keeping of the Courts belonging to Sheffield. There is a smaller wooden box inside that contains a note from Henry, Duke of Norfolk, to the Burgesses. Alas, I have yet to see the contents.”

I hadn’t noticed the narrow stone steps that descended into blackness below. Hollingworth pointed and summoned me to follow. “Careful as we go. These steps are slippery underfoot.” He stooped as we went down into a narrow passage.

The stench here was unbearable, a mix of piss and shit, and there was no light except for a shaft of daylight that came from a grate set high in the wall. My eyes grew accustomed to the darkness, and I saw that there were three huge wooden doors, two open and one closed.

“Look for yourself,” said Hollingworth, and I cautiously looked through one of the open doors. It was a small cell, about eight feet square and barely six feet high, and through it ran a gutter, the source of the unimaginable smell.

Hollingworth rapped his cane against the closed door and peered through a hole that had been cut into it. “See for yourself.” He moved aside to let me look. I thought that it was empty but then I saw movement on the floor, a hunched figure that lay on the stone slabs. “A vagabond!” Hollingworth cried. “The sessions were held yesterday, and this person will be spending a night or two before Sam Hall frees him or sends him on his way to Wakefield.”

I asked who Sam Hall was. “He’s the town constable, amongst other things – beadle, cutler, and now a dealer in china and glass. Upstairs is called Sam’s Parlour, and he earns sixpence for crying the meetings. But he’s not too proud of his official position to eke out a living selling earthenware in the weekly pot market outside.”

We retraced our steps and outside the smell of horse dung was welcome relief to the despicable cells. “A week or so ago, there were stocks here, but we have moved them to where Hick’s Field used to be. They are calling it Paradise Square now, but it’s farther from the town, and punishment is served better. There are too many do-gooders around these days.”

NOTE:

Poetic licence has been used here. William Hollingworth never existed. Had such a meeting taken place then this would have been in the 1790s.

His comments are fictional, while others came from Robert Eadon Leader and a later gentleman called Fred Bland. “When the street was widened, I would have expected this building to be taken down, but it still stands as a disgrace to Sheffield,” was uttered by the historian Joseph Hunter.

Little is known about Sheffield’s ‘first’ Town hall and no sketch exists as far as I am aware. The little we do know is included here.

The last important meeting held in the building was in the 1807 County of York parliamentary election when two of the three candidates – William Wilberforce and Charles Fitzwilliam, Lord Milton – made speeches. The third candidate who fought unsuccessfully for one of two seats was the Hon. Henry Lascelles and the election was called the great struggle between the Houses of Wentworth and Harewood.

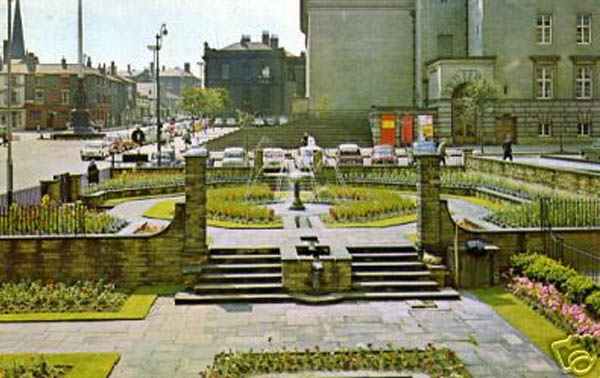

The ‘second’ Town Hall was built at Waingate in 1808, enlarged in 1833, and again in 1867. It subsequently became the Crown Court and is currently empty and in dire condition.

Our ‘third’ and grandest Town Hall opened in 1897.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved