If there had been radio DJs in the 1920s and 1930s, then Henry Hall would have been the equivalent of Terry Wogan, or Ken Bruce. But there were no such things as DJs, and the adoration that existed belonged to bandleaders like Henry Hall, who brought music to the BBC’s infant airwaves.

Henry Hall (1898 – 1989) was born in Peckham, South London, and had no connections with Sheffield. He played from the 1920s to the 1950s, and in 1932 recorded the song Teddy Bear’s Picnic which gained enormous popularity and sold over a million copies.

Hall became bandleader of the BBC Dance Orchestra, and from 5.15 each weekday he gathered a huge following with his signature tune ‘It’s Just the Time for Dancing’ and usually ended with ‘Here’s to the Next Time’.

In 1937, he left the BBC Dance Orchestra to tour with his band, and this brings us nicely to Thursday 12 December 1940.

It was the Second World War, and Henry Hall and his Band were in Sheffield to play at the Empire Theatre on Charles Street at its corner with Union Street.

What follows next is an extraordinary account of wartime Sheffield that I stumbled upon while reading Hall’s autobiography – Here’s to the Next Time – that was published in 1955.

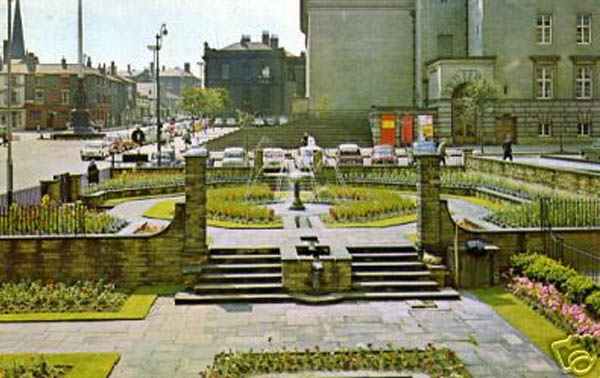

“On Wednesday evening I had supper after the show in the Grand Hotel (now the site of Fountain Precinct) with Jack Buchanan and Fred Emney, who were rehearsing for the forthcoming pantomime. We talked, I remember, of how Sheffield should be quite safe, as it was protected by having a decoy village built some distance outside the town.

“The following evening the warning went, and the German bombers missed the decoy completely and began to bomb the centre of Sheffield!

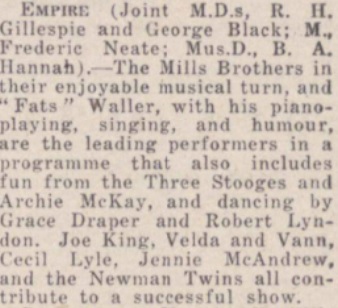

“One of the first incendiaries landed in front of the Empire just before we were due to appear. The manager, Fred Neate, dashed round and asked me to play one number, then announce that there was a fire and would the audience please leave as quietly as possible.

“I walked on to the stage and said, ‘We should like to play you the popular song, Six Lessons from Madame Lazongo,’ and almost before we began there was a tremendous explosion as a bomb landed outside the Stage Door, wrecking the side of the theatre.

“Luckily the stage itself stayed put, so we finished the number. I made the announcement as requested and we went into one of Freddie Mann’s comedy numbers, The Musical Typist, while the audience left in a hurry. It was a very fast number, but it had never been quite so fast as Freddie played it that night!

“We stood in the safest looking corridor for some three hours until there was a lull, and then I made a dash for the Grand where I was staying, only a few hundred yards away.

“Just before I reached the hotel the bombs began to fall again, and I was literally blown through the swing doors to land on the foyer carpet. When I had recovered sufficiently I joined the rest of the guests in the restaurant, which was thought to be directly under the main block of the hotel and consequently the safest place.

“As soon as the all clear sounded, about seven in the morning, I went to the theatre to try to make arrangements. It was out of commission, transport everywhere was disorganised and no trains were running. I left a notice asking all who could to meet outside The Sheffield Daily Telegraph Office at 10.30, when there would be transport to Chesterfield. Then I dashed back to the hotel to try to arrange it.

“Because of the dislocation of communication, I had to do it by six ‘phone calls. I rang the stage manager on one exchange, he rang a friend, and so on, until someone got through to Chesterfield and brought a coach over.

“With all my journeys between theatre and hotel, the orchestra had lost all trace of me, and were astounded when I arrived for the coach – my constant disappearances had led to me being ‘posted missing.’

“However, we got safely to Chesterfield, caught the midday train to Bristol and arrived at midnight just in time to hear their sirens beginning to blow!”

How lucky most of us are to have never witnessed such scenes!

This story leads to one that my dad told me recently, and would have taken place at the same time that Hall was desperately arranging his transport away from Sheffield.

He was eleven, and the morning after, walked with his Aunty Vera from Milton Street to Grimesthorpe to make sure that her boyfriend Jim’s family had survived.

“At the top of The Moor, Woolworths was a sheet of fire, and there were bodies laying in the road, and that was a sobering sight. But I realised that they weren’t bodies after all, but were actually mannequins that had been blown out of the shop.

“Pinstone Street was closed for access, and so we diverted along Union Street but found it blocked by rubble from the Empire Theatre that had collapsed into the road. We climbed up and over the debris before continuing along Norfolk Street, into Fitzalan Square, then down Haymarket and on to the Wicker. Most buildings were ruined and ablaze.

“At Wicker Arches, a bomb had gone straight through the railway line and through the bridge without exploding (the repairs still visible today), but we still managed to get through, and there was a place on Spital Hill that had wooden chairs piled high and had caught fire and were well ablaze.

“We walked all the way to Grimesthorpe and after finding that the Wells family was safe, walked all the way back again.”

Alas, for the Empire Theatre, it lost one of its two turrets which capped the towers on either side of the facade, and buildings on either side of the theatre were destroyed. It closed in May 1959 after being sold to a developer and was demolished two months later.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.