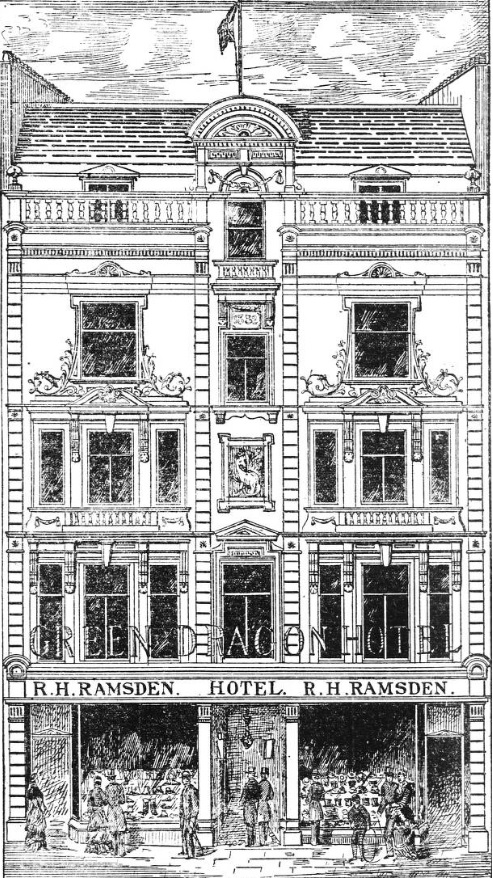

The year is 1874, and on a road, yet to be named, there is a conspicuous addition to Sheffield’s public buildings.

“Heavy? Well, a light and airy edifice would hardly bear the weight of the abominable clouds of smoke that smother the locality, and that make one shudder to see a handsome building exposed to their defilement,” said the Sheffield Independent.

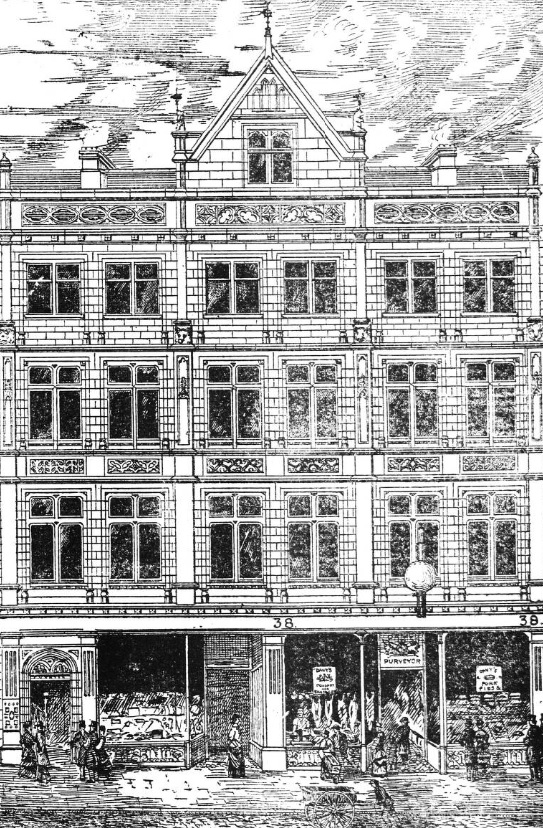

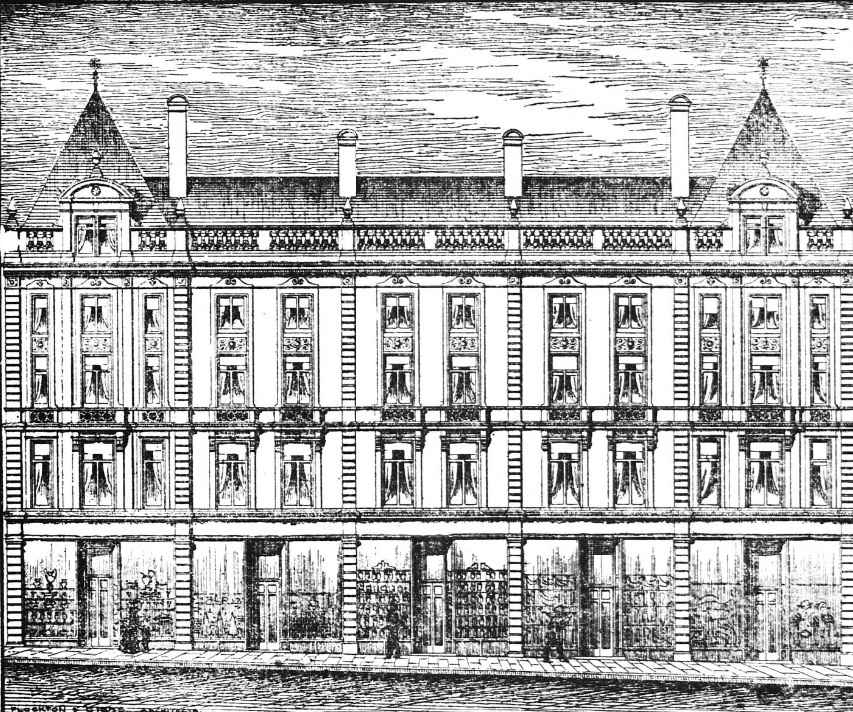

“Externally the building is almost finished, and as nearly all the scaffolding has been removed, its architectural features are now fully revealed. Whether considered from an architectural point of view or simply as a business establishment, the building is undoubtedly the finest erection in town.”

People of my generation must hang our heads in shame because we have woefully neglected this building over the past fifty years, and it is in a sorry state.

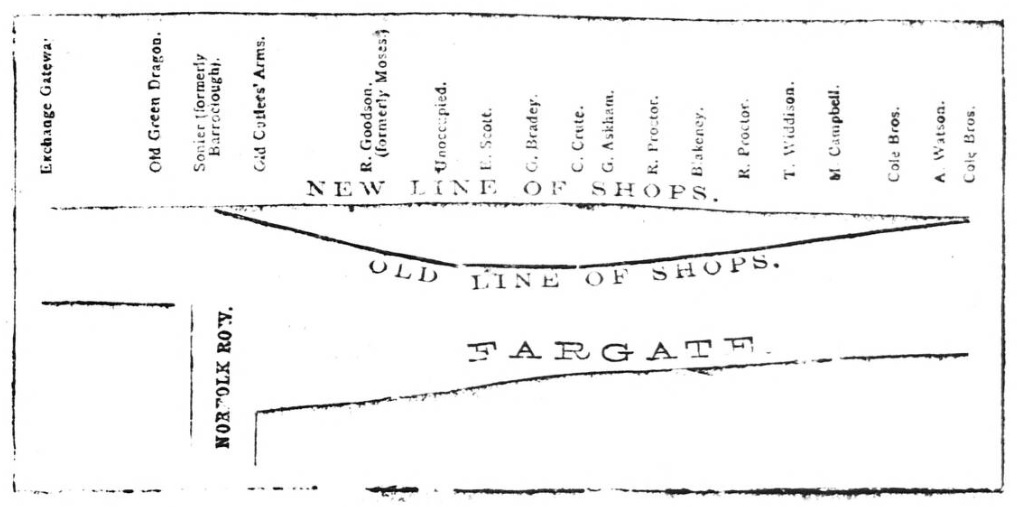

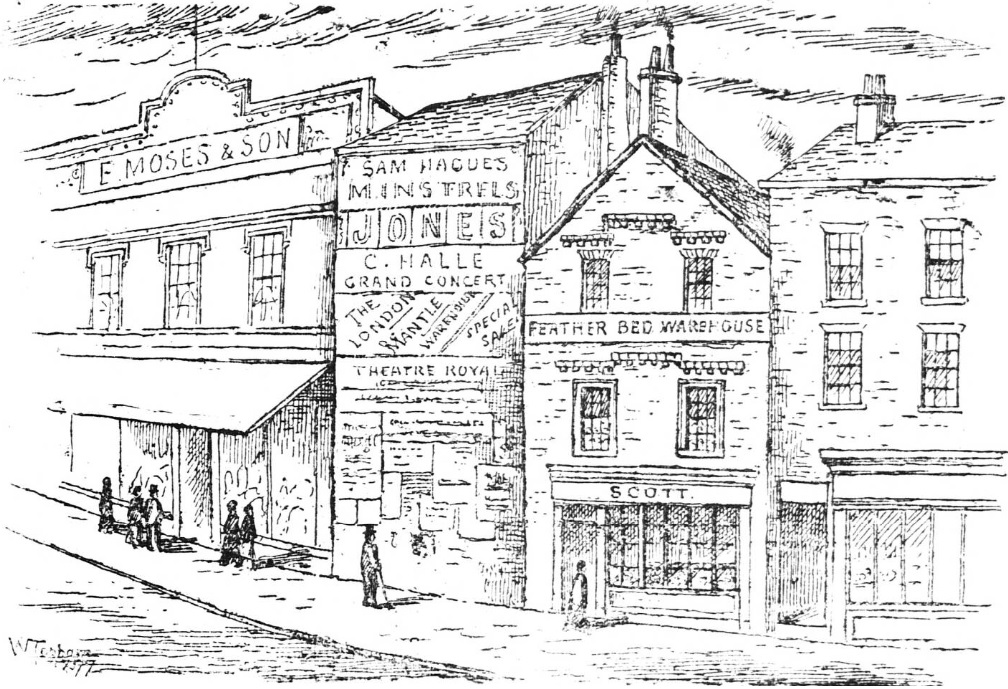

It was completed in 1875 for the Sheffield United Gas Company, and after the expansion of works at Neepsend, and new works at Grimesthorpe, there was no longer any need for its original works at Shude Hill. It coincided with the town council’s ambitious road improvements programme and the creation of Midland Railway’s new station in the 1870s.

Four new approach roads were created to what is now Sheffield Station, including one from Haymarket down to Sheaf Street, and required the construction of a bridge over Shude Hill, and allowed construction of new offices and showrooms for the gas company.

When it was built, the new road still lacked a name causing the Independent’s ‘Spectator in Hallamshire’ to say, “What is the name of that street? I never know how to call it?”

It became Commercial Street, the history of which I’m currently preparing for the Sheffield Star, and so will avoid further comment here.

The building (without fittings) cost £25,000.

The architects (Hadfield and Son) adapted a style of architecture affected by old Venetian merchants; the general effect was bold and massive; the details, not without their elegances, were in perfect keeping, while the granite doorways and monolithic pillars – some 14 feet in height and of splendid Mull of Ross stone – were quite imposing. The carving on the front elevation was sculpted by Thomas Earp, who worked on many Gothic churches and is perhaps best known for his 1863 reproduction of the Eleanor Cross which stands at Charing Cross in London.

The interior of the building seemed admirably adapted for its purpose.

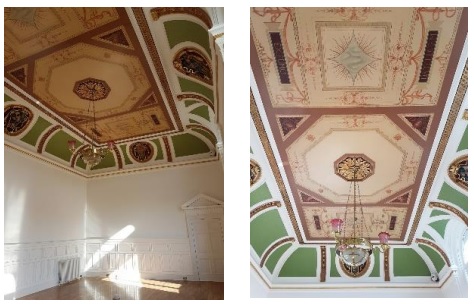

A few steps led into what was the general office, a magnificent room capable of accommodating fifty clerks. The ceiling was handsomely coved and surrounded by a spacious dome which was filled with glass, designed by John Francis Bentley, and brilliantly painted with heraldic designs. All the desk fittings were fine Spanish mahogany. To the left of the entrance was the show room, fifty feet in length.

General Office. Image: Creative Heritage Consultants

From the vestibule or entrance hall, was a handsome corridor, with finely coffered ceiling, leading to a grand staircase, the steps of which were Hopton Wood marble.

At the top of the stairs there was another hall, which communicated with the board room, with coved ceiling by Hugh Stannus, the engineers’ drawing office, and several other rooms, all of which could be thrown together ‘en suite’ if desired.

The foundations were in Shude Hill, a great depth below the level of the new street; and the two storeys down there provided storage space.

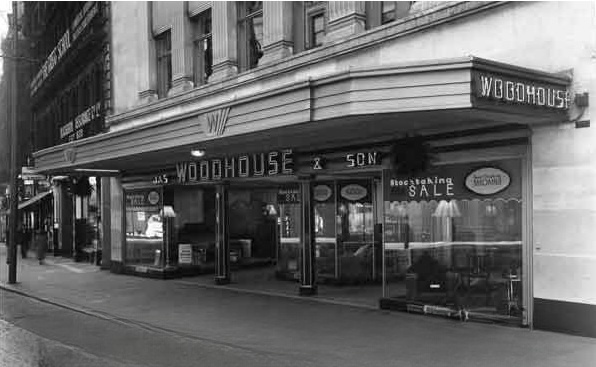

By 1890, the company had extended its premises northwards along Shude Hill, with a contrasting red-brick warehouse, and in 1938 a white Portland stone extension to the offices was built on the west side of the Commercial Street building. In the characteristic art deco style of the time, it has carvings by Philip Lindsey Clark, and is no longer connected to the original building.

The 1948 Gas Act brought together over one thousand privately owned and municipal gas companies and created twelve area gas Boards, and these offices and showroom were used by East Midlands Gas. It lasted until 1972 when the British Gas Corporation was created and moved elsewhere.

It attracted no buyers, was listed by English Heritage (now Historic England), but despite this, was identified for demolition. It survived a 1977 inquiry and was sold to a local businessman who had plans to convert it to a hotel and conference centre, which never materialised but in the 1980s, the ground floor was converted to ‘Turn Ups’ nightclub and ‘Bloomers’

The Shude Hill warehouse wing became Tower Cash & Carry. And in 1990 the building was acquired by Canadian Business Parks of Bedfordshire with plans for restoration.

The building adopted its new name, Canada House, but notwithstanding regeneration of the city, the company hit financial difficulties and the building was never developed.

Vacancy led to dereliction through rainwater ingress caused by the stripping of lead from the roof by vandals, and the theft of period fireplaces.

The council served an urgent works notice to effect repairs to the building’s owner in 1996, and ownership was subsequently secured by English Partnerships, the government’s regeneration agency.

It was most recently used as a head office by owner Panache Lingerie, with a Chinese buffet on the ground floor. It is now occupied by just one commercial tenant, who occupy the first floor of the Shude Hill wing only.

However, the future looks the brightest it’s been for many years because plans have been lodged to convert it into a new music hub.

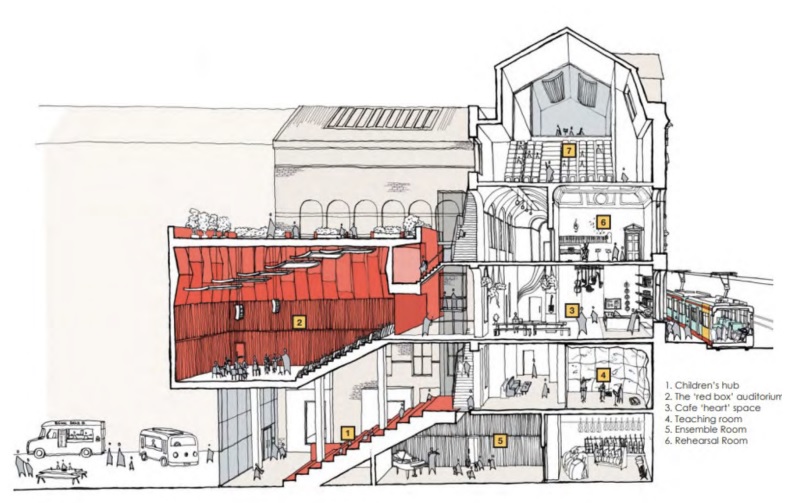

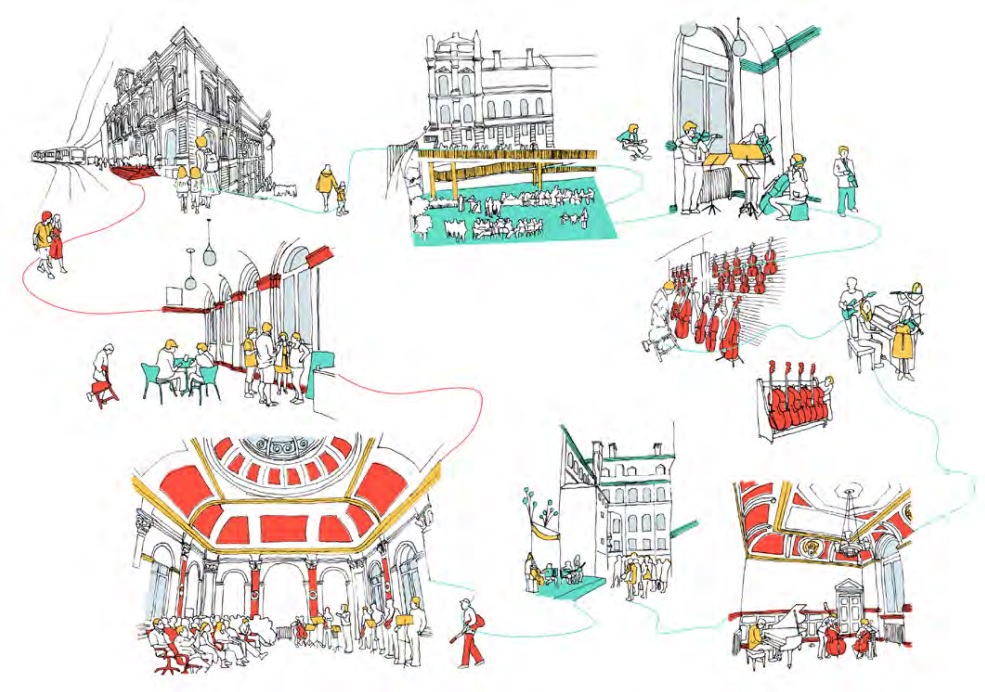

The proposed ‘Harmony Works’ development, from Sheffield Music Academy and Sheffield Music Hub, aims to create a home for music education in the region.

Planning permission is sought for the refurbishment, change of use and extension of the Grade II* listed building.

The proposed development would include a performance space for an audience of 300, two rehearsal rooms accommodating 80 musicians, 15 smaller ensemble rehearsal rooms, 20 individual practice rooms and a substantial instrument store.

Plans also include office space, a café, breakout spaces and ancillary accommodation.

©2022 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.