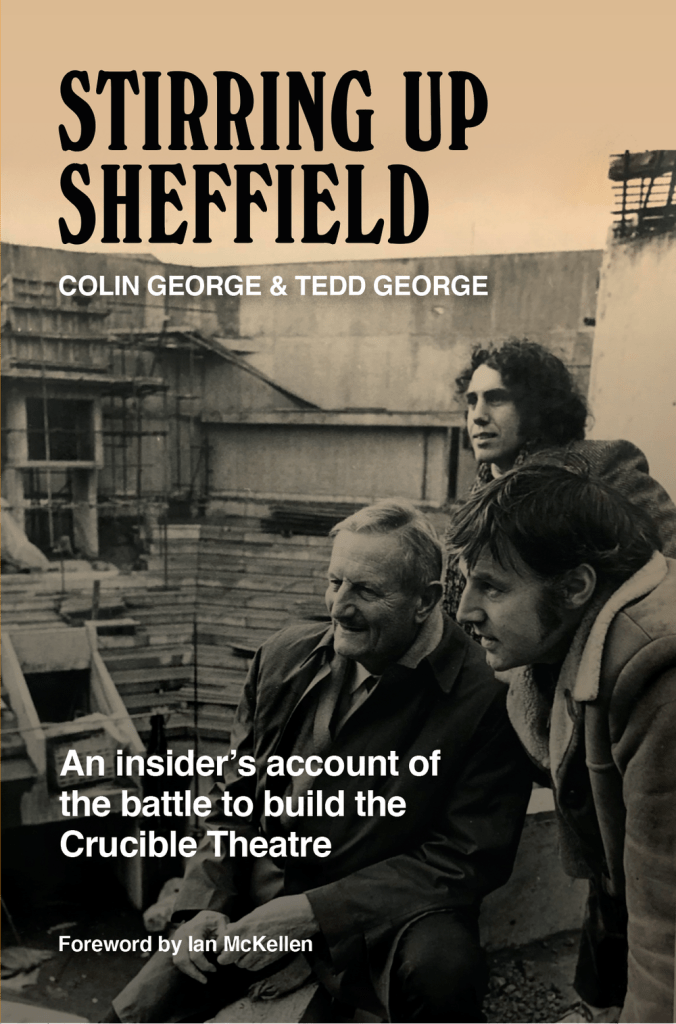

Here’s a book that will become a collectors item, and a must for those who appreciate Sheffield’s recent history. ‘Stirring Up Sheffield,’ a substantial book, is written by the Crucible Theatre’s first Artistic Director, Colin George, and his son, Tedd George, and will be published by Wordville Press on 9 November 2021.

This is the extraordinary story of a group of visionaries who came together to build the revolutionary thrust stage theatre. The radical design they proposed for the auditorium—which redefined the actor/audience relationship—aroused fierce opposition from Sheffield’s conservative quarters and several of the era’s theatrical luminaries. But it also galvanised a new generation of Britain’s actors, directors, designers and playwrights who launched a passionate defence of the thrust stage and its theatrical potential.

Colin George was the founding Artistic Director of the Crucible Theatre. Born in Pembroke Dock, Wales, in 1929, Colin read English at University College, Oxford, and was a founding member of the Oxford and Cambridge Players. After acting in the repertory companies of Coventry and Birmingham, Colin joined the Nottingham Playhouse in 1958 as Assistant Director to Val May. In 1962, he was appointed as Assistant Director at the Sheffield Playhouse, becoming Artistic Director in 1965. Colin played a leading role in the creation of the Crucible Theatre, which opened in November 1971, and was the Crucible’s Artistic Director from 1971 to 1974.

During his tenure Colin also established Sheffield Theatre Vanguard. This innovative scheme took theatre out of the Crucible to engage with the wider Sheffield community. Sheffield Theatres continues to build on his legacy with Sheffield People’s Theatre, a cross-generational community company which trains and nurtures the aspirations and skills of local people through special one-off projects and collaborations.

He later worked as Artistic Director of the Adelaide State Theatre Company (1976-1980), as Artistic Director of the Anglo-Chinese Chung Ying Theatre Company (1983-1985) and as Head of Drama at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts (1985-1992). Colin joined the Royal Shakespeare Company as an actor (1994-96 & 1997-99).

In 2011 Colin was invited by the Crucible’s Artistic Director, Daniel Evans, to join the Company for the 40th anniversary production of Othello. This was to be his last theatrical performance and, fittingly, it took place on the thrust stage he had created. Following Othello, Colin produced the first draft of this book, before his death in October 2016.

The introduction is by Sir Ian McKellen:

“Adventures need heroes and here its principal one is Colin George, the first artistic director of The Crucible Theatre, who in this memoir recalls in fascinating detail how, aided by others locally and internationally, a dream came true. Here, too, there are troublesome villains, who failed to share our hero’s imagination and determination.”

© 2021 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.