I need you to use your imagination.

We are on Barnsley Road, heading towards Fir Vale, an area adjacent to Page Hall, where a large Slovakian Roma community lives. Page Hall has attracted national attention for all the wrong reasons. It has an unwanted reputation for crime and disorder.

But before we reach Fir Vale, and the sprawl of the Northern General Hospital, we come to a set of traffic lights, at the junction with Norwood Road. On the corner, we can see an abandoned and boarded-up former care home. Steel-mesh barriers surround it, and graffiti covers most parts. It won’t be long before someone sets it on fire, and it will be gone.

We carry on down Barnsley Road and turn left into Crabtree Close. We park the car and retrace our steps to a patch of scrubland where a sign welcomes you to Crabtree Ponds Local Nature Reserve.

Slipping through the trees, we descend a rough path, and at the bottom is a most unexpected sight. A beautiful expanse of water, with carefully made walkways around it, surrounded by tall trees and thick vegetation. All you can hear are birds singing, and the distant hum of traffic.

A man with a big dog sits on a bench. He is drinking from a cheap bottle of wine. He is drunk, but he doesn’t care that we have disturbed him. “Reyt, pal,” he calls, and sits back to enjoy the last of the day’s sun. We walk past him, along wooden planks suspended above water, and climb the steep hillside, back towards that decaying care home. Nearby, an ambulance wails its way to the hospital.

But imagine we could go back in time.

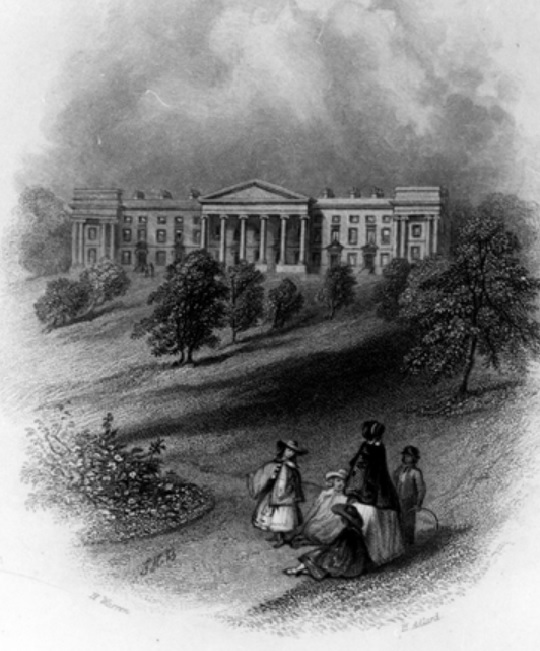

We are in the mid-1800s. Like today, the birds are singing, but the only traffic is a horse and cart gently clattering along the other side of a huge stone wall. We have walked around the ornamental pond, admired the fountain at the centre, and said good evening to a beautiful Victorian lady taking the summer air.

We climb the neat, terraced gardens, up exquisitely carved steps, absorb the sweet fragrances, and walk across the manicured lawn towards the big house. It looks splendid as the sun slips behind its sloping eaves, and shadows fall across the decorative gardens. It will soon be night.

We sit on a garden bench and look across the valley, to the meandering stream below, the ponds with their delicate fish, and the trees and fields that stretch over to Wincobank Hill.

Let us hope that this landscape remains as it is forever.

***

In 1884, a newspaper reported that Crabtree Lodge was a pleasantly-situated residence, in a district of Sheffield which had grown very rapidly. Pitsmoor had lost its rural charm, but this big house remained at the corner of Crabtree Lane.

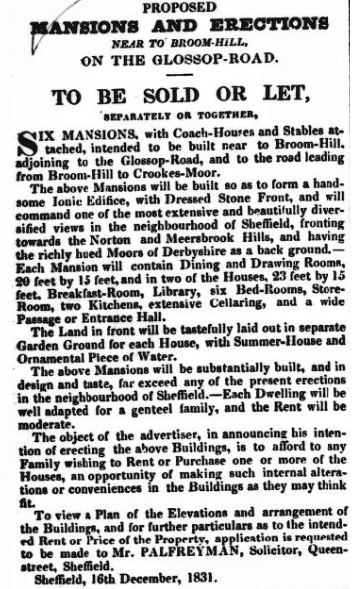

It was a mansion in the picturesque old English style built in the nineteenth century, allegedly for a Mr Rotherham.

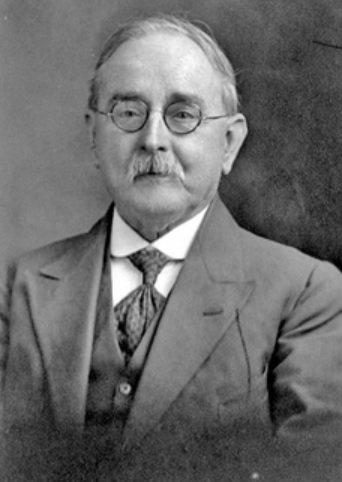

It later became home to Charles Atkinson, J.P. (1800-1879), chief partner in the firm of Marriott and Atkinson, Fitzalan Works, Attercliffe, one time Mayor, and Master Cutler. He had started as a travelling salesman for George Marriott and took his daughter as his first wife.

In 1875, he published a pamphlet called ‘Sheffield as it was; Sheffield as it is; Sheffield as it should be; by an old Grammar School boy of 1808.’

“I have endeavoured to show what Sheffield was 60 years ago, and what it is now. With all its increase of population and wealth, and yet without a good street as a leading thoroughfare, the centre of town a complete blot; the public buildings scarcely reaching to mediocrity and situated as they are in bye streets. While its merchants and manufacturers have made advancement in the race of improvement, the town itself remains much the same as it was in the days of Chaucer.”

On his death in 1880, the house and its contents were put up for sale and described thus: –

“The house contains a spacious entrance hall, noble dining room, excellent drawing rooms, library, and boudoir, loft corridors, good bedrooms, pantries, kitchens, larders, and every convenience. There is a four-stall stable with coach-house, and coachman’s room over. A small conservatory, with mushroom beds and potting sheds. The grounds of over 2 acres are tastefully laid out, being terraced up to the house, with an ornamental lake below, having a fountain in the centre. There is also a well-stocked and productive kitchen garden. There is also three acres of pastureland. It is held under two leases from the Duke of Norfolk.”

It was acquired in 1881 by Edward Tozer (1820-1890), a partner in the firm of Steel, Peech and Tozer, steel manufacturers, another Mayor of Sheffield, and twice Master Cutler of Hallamshire.

He was a rags-to-riches story, born in comparative poverty, and rising to become a partner in one of Sheffield’s best-known firms. He was born at Clifton, near Bristol, the son of a brewer, who came to Sheffield. Following his father’s death, he was brought up by his mother who opened a school in Victoria Street.

At the age of eleven, Tozer started work with Sanderson Brothers on West Street and remained to become Managing Director. He eventually left to and joined Henry Steel, T. Hampton, and William Peech in the management of the Phoenix Bessemer Works

It was during Tozer’s time that tragedy occurred at Crabtree Lodge.

In 1886, his youngest daughter, Margaret, aged 19, suffering from ‘religious mania’, went to an upstairs room and committed suicide by swallowing a bottle of sulphuric acid.

Edward Tozer died, aged 70, in 1890, and Crabtree Lodge passed to Francis Markham Tindall, head of Thomas Marrian and Co, Burton Weir Brewery, Attercliffe, who died in 1902.

It is not without doubt that by now the city had encroached upon Crabtree Lodge and it spent years being offered for sale or to rent. In 1907, it was briefly home to Ernest Adames, a district manager of an assurance company, but appears empty until World War One.

In 1916, the Y.W.C.A. secured the lease as a hostel for the recreation and rest of women and girls coming to Sheffield and engaged in munition work.

“The house is going to be so nice when it is finished,” said Miss Goldie, the warden.

“The house has been unoccupied for some time, and the grounds have suffered in consequence, yet such imperfections as a break in the stone balustrade which surrounds the delightful terrace only seems to give an air of romance and makes the house appear older than it probably is.

“The large dining hall with panelled dado, surmounted with green duresco and dark oak ceiling, is considered one of the finest rooms in Sheffield, and here the girls will sit at tables laid for six and look out from a large lattice-paned window over a stretch of country blocked on the horizon by Wincobank Hill.”

After the war, Crabtree Lodge, referred to as The Hostel, was managed by a committee of ladies, although still affiliated to the Y.W.C.A., and lasted until 1927. It was advertised as a private hotel or boarding house but survived as a place for meetings and functions with garden fetes regularly taking place in the grounds. It was later converted into flats, and there is a suggestion that the grounds may also have been used as a T.A. Centre.

We might consider the area to be called Burngreave now, and the lodge was eventually demolished, the site used as the Norbury Home for Elderly People.

But its gardens and ponds remained and today form Crabtree Ponds, a large area of standing water abundant with aquatic life such as rudd, roach, perch, crucian carp, sticklebacks and even eels. Bats fly from nearby Roe Woods to feed on the ponds.

©2022 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.