Let’s talk about West Street, a haven for bars, restaurants and takeaways, a road that has changed considerably since the 1990s.

However, a look back in history suggests that there were attempts during the 1920s to make West Street one of the city’s main shopping thoroughfares.

In 1929, the Sheffield Daily Telegraph made the following observation: –

“West Street seems intent upon coming into line with other busy shopping centres in the city, and of acquiring the same prestige. Many new shop premises have opened, and recently the removal of a length of hoarding revealed an array of smart, single-fronted shops.

“Such signs are distinctly encouraging, for although many roads radiate from the hub of Sheffield – High Street and Fargate – yet, West Street, with its width and fine approach, appears to be the natural outlet and extension of the shopping centre of the city.

“There are other reasons why the street should continue to develop. It is the main approach to many important public buildings, such as the Royal Hospital, the Edgar Allen Institute, Jessop Hospital, Children’s Hospital, the Applied Science Department of the University in St. George’s Square, Weston Park, Mappin Art Gallery, Western Bank Buildings of the University, and Glossop Road Baths.

“Hundreds of persons daily pass and repass along West Street, on their way to and from these buildings, and motorists going to Derbyshire also make great use of this route out of the city.

“Despite the fact that West Street is served by an excellent service of Corporation tramcars and motor-buses which run to a number of outlying residential districts, it has to be admitted that the road has not, hitherto, enjoyed the prosperity that would appear to be its right.

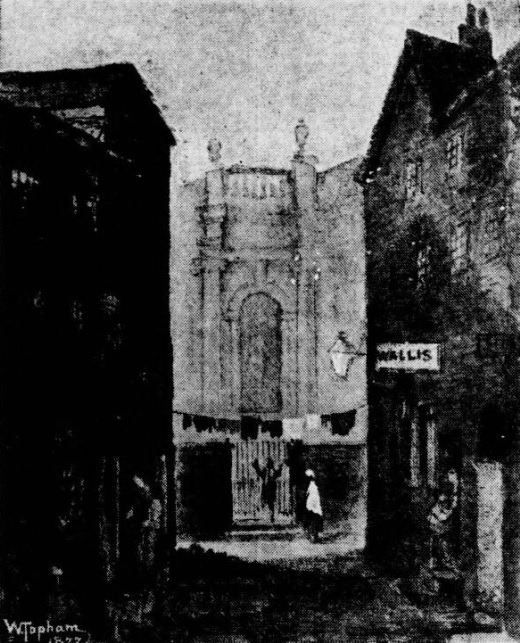

“It should always be borne in mind that West Street has been developed by private enterprise, Sheffield Corporation do not now possess a single square yard in this street, but there was a period when they owned a considerable area of freehold land there.

“When this was in their possession, the Corporation did not do anything to encourage traders by building new shops, and otherwise improving the amenities of the highway, but simply erected hoardings around the land, making it an unsightly blot in the neighbourhood.”

An interesting look at the past that also throws up some noteworthy observations.

Take, for instance, the fact that all premises built had to be three storeys, or over, and conform with the adjacent property.

Gone were the days of narrow, mean streets, with high crooked houses, each one with a dark and dismal “basement,” and of low, badly lit shops, with small window space. In their place were wide, low windows and a spaciousness about the new properties.

And we also discover that Sheffield Corporation, at one time, considered building a square in West Street, about 5,200 square yards in size, the plan later abandoned as being too costly.

The shopping centre that was promised never really materialised, although there were several specialist and prestige shops. But West Street did eventually thrive.

As the decades rolled on, the University of Sheffield expanded, with West Street becoming the gateway between the city centre and campus buildings. It soon became obvious that the street’s traditional public houses would become popular with students – once described as the “West Street Run” – a turn of events that eventually created the trendy bars that we see today.

And, of course, city living became popular again, particularly along West Street, with numerous new-build apartments, alas creating conflict between those living in them, and the businesses that brought prosperity in the first place.