This afternoon (Sunday 29 September), a group of people will meet in a Sheffield city centre bar. There will be reunions, memories shared, but the event will have an air of sadness.. Friends and former work colleagues will see each other for perhaps the last time.

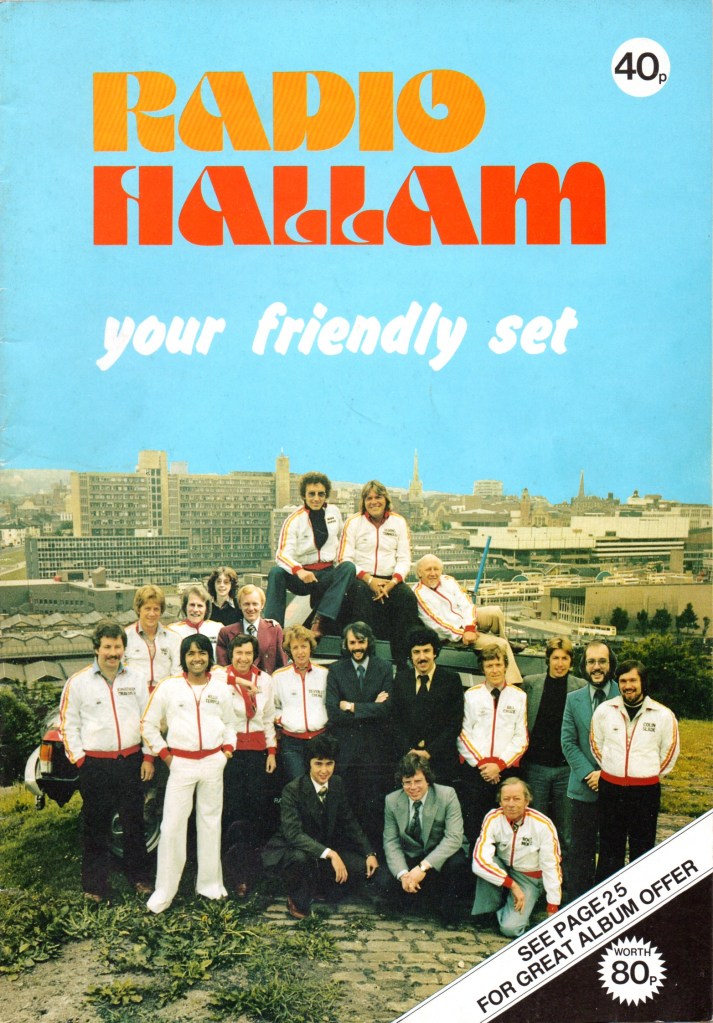

If things go to plan, one of those attending will be 85-year-old Keith Skues, the man responsible for giving us Radio Hallam, one of the UK’s pioneer commercial radio stations. It started broadcasting on 1 October 1974, and this coming Tuesday will be the fiftieth anniversary of its launch.

The irony is that its present owners, Bauer Media, chose its Golden Anniversary year to kill the name off – it is now Hits Radio South Yorkshire – but the spirit of the radio station, and its ability to be local, had disappeared many years ago.

Until the early 1970s, the BBC had the legal monopoly on radio broadcasting in the UK. Except for Radio Luxembourg, and for a time in the 1960s, the offshore ‘pirate’ broadcasters, UK listeners had limited choice. Edward Heath’s Conservative government changed that and allowed the introduction of commercial radio to compete with BBC local radio services.

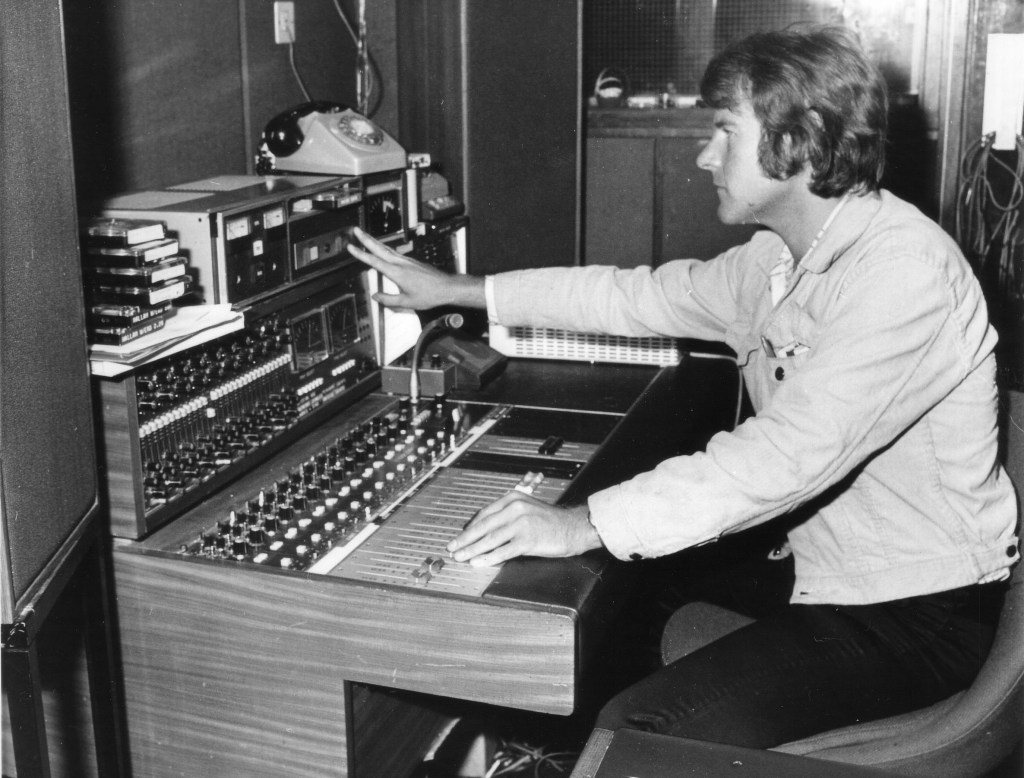

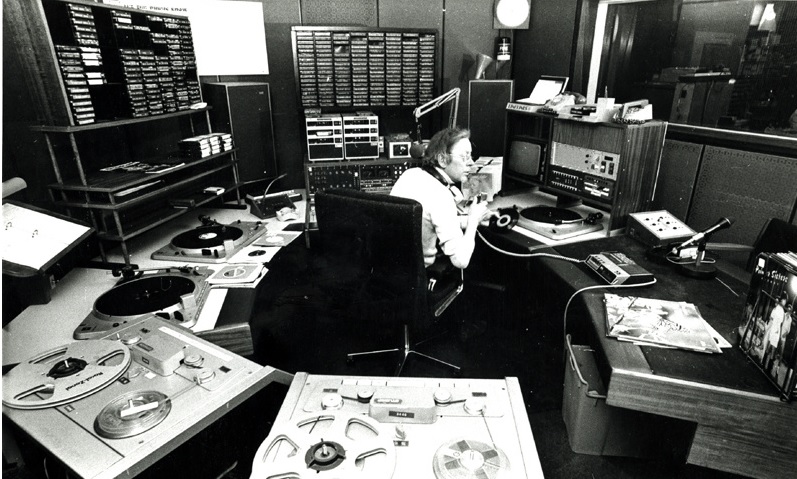

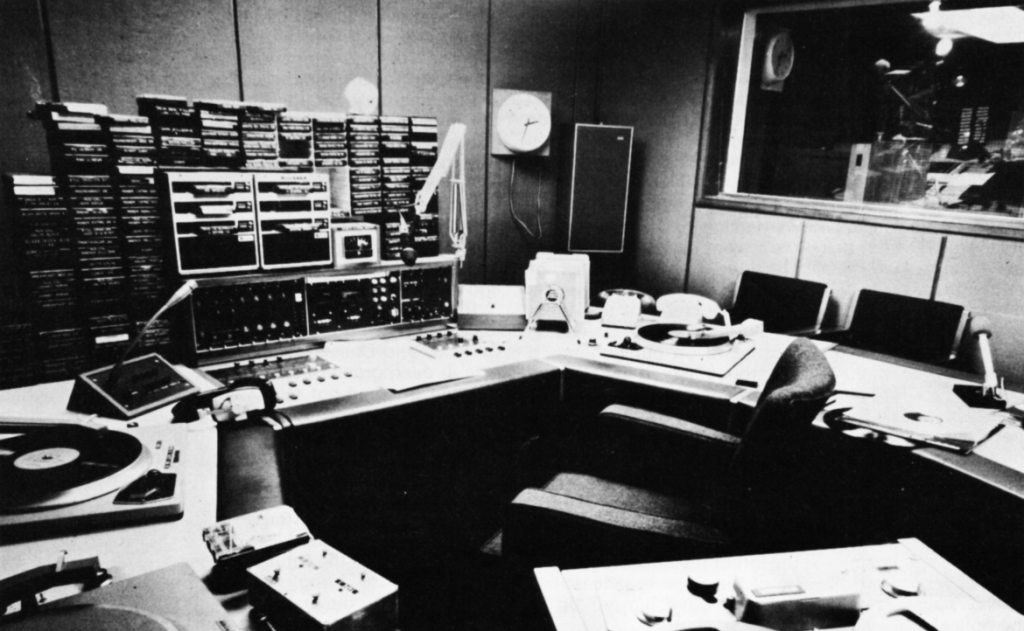

In October 1973, London Broadcasting Company (LBC) started broadcasting, closely followed by Capital Radio, and household names like Radio Clyde, BRMB, Piccadilly Radio, Metro Radio, and Swansea Sound. A year later came the launch of Radio Hallam from studios on the upper floors of the Sheffield Newspapers building at Hartshead with its strapline – ‘It’s nice to have a radio station as a friend.’

It beat off one other consortium for the franchise, but there was a merger after the licence had been issued. The Managing Director was Bill McDonald who at one time had worked for A.C. Nielsen rolling out overnight ratings for TV across the USA. He spent some years in New York in the early 1960s with a background in newspaper and commercial radio advertising but returned to England and the newspaper business and used his expertise to attract Radio Hallam shareholders including the S&E Co-op, B&C Co-op, Sheffield Newspapers, Trident Television (owners of Yorkshire Television), the Automobile Association, Kenning Motor Group and trade unions – USDAW and GMWU. The start-up cost for the station was £300,000 (about £3.9M today).

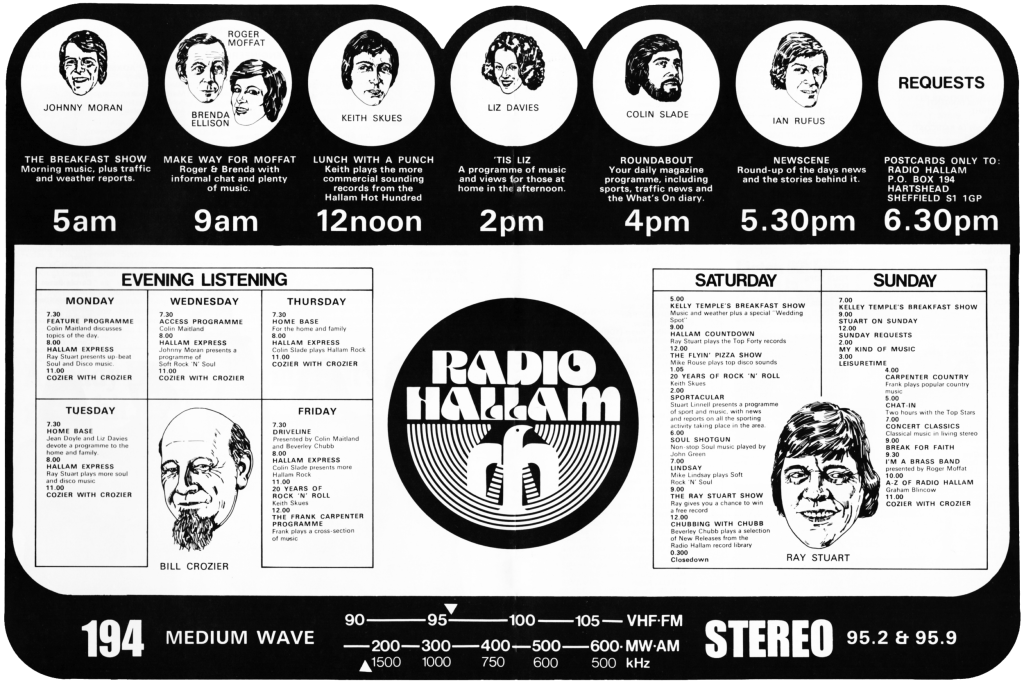

From the start, Radio Hallam’s strength was the ‘rebel’ disc jockeys it took from the BBC – Keith Skues as Programme Controller, Roger Moffat, Bill Crozier, and Johnny Moran, briefly joined later by Bruce Wyndham – and the emphasis was on professionalism. There had been another BBC staffer, Peter Donaldson, who was to have presented the afternoon magazine programme ‘Roundabout’ but got cold feet and left before the station launched. (Yes, it was THE Peter Donaldson, who became a BBC Radio Four icon).

“Whilst in London I formally approached Roger Moffat (returning a favour as it turns out), Johnny Moran, and Bill Crozier, and to my amazement they all agreed to leap into the unknown and come with me to Sheffield,” said Skues. “All the time I was holding auditions for local broadcasters. We received applications from over 700 hopeful Disc Jockeys, but I could only take three, all of whom had worked with BBC local radio.”

After only a few months, a dipstick survey suggested that Hallam had 25 percent of the audience, placing it second after Radio 2 with 26 percent and ahead of Radio 1 (24 percent) and BBC Radio Sheffield (19 percent).

“Ours is a complete mixture. We are going for anybody from 18 to 40 -olds, and we get lots of requests from 70 and 80-year-olds.”” said Keith Skues at the time.

The schedule was an easy listening mixture of hit 40 and middle-of-the-road pop during the day, heavier rock and jazz for students in the evening, with minority interest programmes slotted in at the weekend.

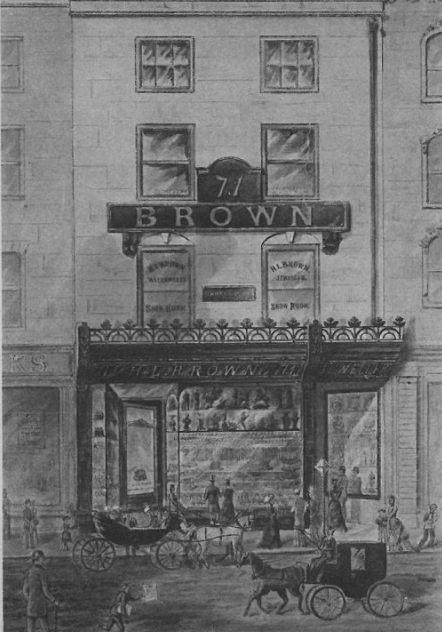

The Top 40 singles were based on local record shop returns (remember Bradleys?); another 40 LPs were chosen by seven disc jockeys and there were twenty new releases on the playlist. The first record after the news was always from the top ten; the second was between number 11 and 40; the third was a climber (new release); the fourth was an oldie (anything from five to fifteen years); the fifth was again between 11 and 40: and the sixth was an album track. The cycle was then repeated. And Skues said that it got very high ratings. “Where Hallam does seem to score is that we don’t do a lot of chat – there are no requests, no name checks even during the format hours.” Neither were there any phone-ins, although the idea had been considered.

BBC Radio Sheffield nicknamed it as the ‘pop and prattle station,’ but the former BBC presenters impressed with their individual personalities.

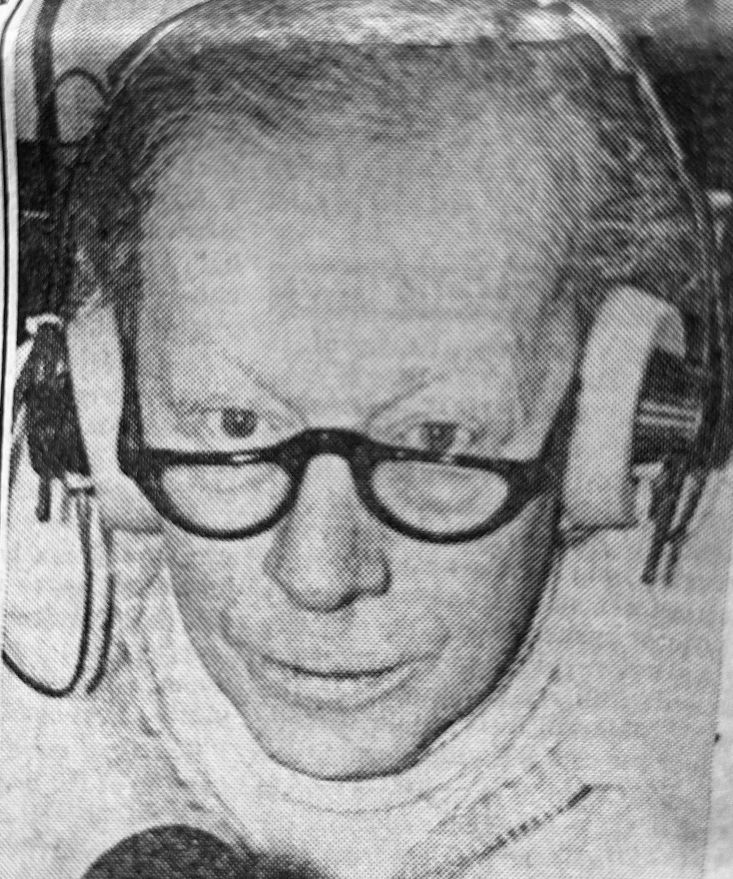

Keith ‘Cardboard Shoes’ Skues (Lunch with a Punch) was determined to get into radio from a young age. Roger Moffat let him attend live broadcasts of Make Way for Music with the Northern Variety Orchestra in Manchester, and recommended the Forces Broadcasting Service as a possible route into the profession. Skues took that advice a few years later when he was called up for his National Service and posted to British Forces Network (BFN) in Cologne. He returned to the UK in 1964 to join pirate station Radio Atlanta which then merged with Radio Caroline. He joined Radio Luxembourg for the CBS Record Show and presented on Radio London until 1967 and the introduction of the Marine Broadcasting Offences Act. He was at the start of Radio 1 and remained with the BBC until leaving to set up Radio Hallam.

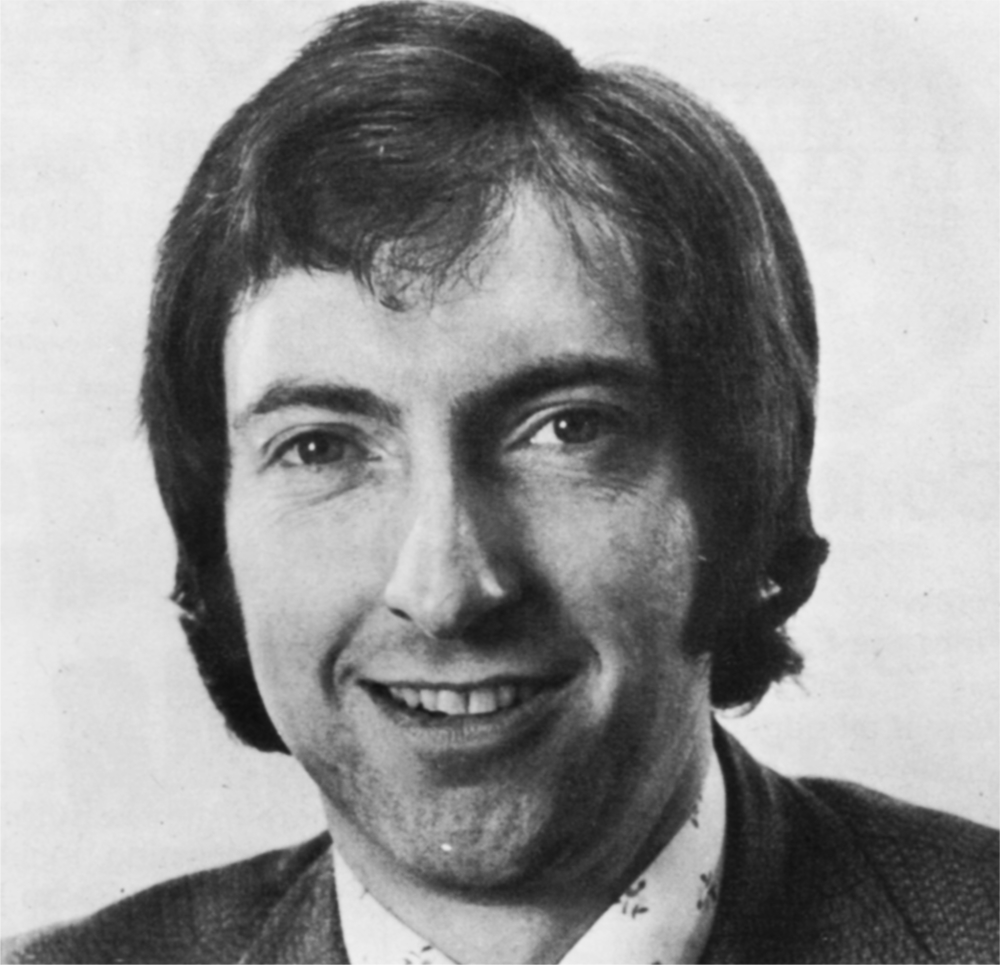

Roger Moffat (what a bloody awful place Sheffield is) gave the station an air of irreverence: playing a blank tape after failing to interview a pop prima donna, telling the early morning disc jockey who phoned him with a live alarm call, ‘I don’t want a railway station as a friend’; deviating from the playlist, purporting to be the station’s Royal Correspondent, an obsession with ‘Royal Hackenthorpe’ and upsetting everyone whether they were a bus driver or Elvis Presley fan. He’d been sacked by the BBC three times, but was a storyteller, such a consummate one that while you never knew if it was true, it didn’t really matter.

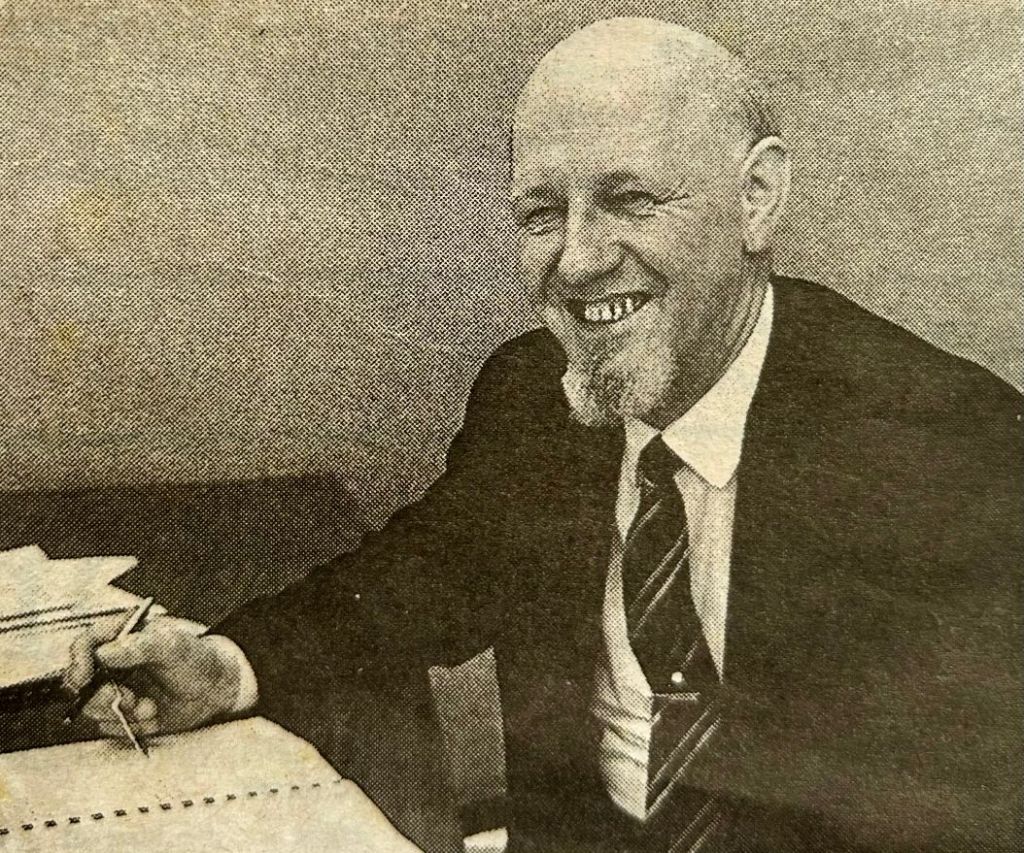

Bill Crozier started with a middle-of-the-road late night show, ‘Cozier with Crozier’ and catered “for the old and lonely.” A distinctive figure in his opera-style cloak and his goatee beard, one of his trademarks was a twittering bird, Florence the Nightingale in the background. He also presented the evening request programme as the friendly host uncle. It came naturally to him for he had been the popular Cologne end of the BFN/BBC Two-Way Family Favourites programme with Jean Metcalfe from 1958 to 1965. After BFN, Crozier switched to the BBC’s Light Programme and Radio 2 which best suited his choice of music from the forties and fifties. He was also a producer of the Jimmy Young Show.

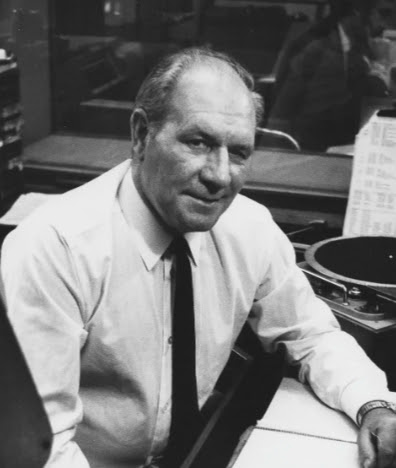

As breakfast show presenter, Johnny Moran was the first DJ heard on Hallam. His mother Phillis had emigrated from Sheffield, and now found himself in her home city via Radio Luxembourg and Radio One. Skues had re-established contact with Moran at a party given for the singer Barry White, and with his BBC career over, he’d been plying his trade for the British Forces Radio Network and was keen to make the switch. Famously, the first record he played on Hallam was Kiki Dee’s ‘I’ve Got the Music in Me’ that stuck after a couple of minutes.

Let us not forget Bruce Wyndham (because we have), a man with a theatrical background whose family had connections with the Wyndham Theatre in London. He joined the BBC in 1948 and remained until 1976 before tasting commercial radio with Radio 210 in Reading and Radio Hallam in 1978. “A lovely cheerful character who would always crack a joke at his own expense,” said Alan Biggs who had to report the death of his colleague after he’d collapsed and died at the station while preparing for a late night programme.

Aside from the BBC personalities, Radio Hallam would introduce other presenters during these golden years – Ray Stuart, Colin Slade, Kelly Temple, Brenda Ellison, Cindy Kent, Gerry Kersey, Dave Kilner, Dean Pepall, Howard Pressman and many more – and furthered the careers of future radio industry heavyweights like Ian Rufus, Stuart Linell, and Ralph Bernard.

Let’s not be mistaken for thinking that it was all about music because the early independent local radio stations had to be friends to everyone – including every music genre – and phonographic performance rules meant that they were restricted to the amount of needle time played on air. The gaps in-between were given over to talk content. Radio Hallam’s news was local, operating throughout the day, and into the night. One of its quirks was that it was at five minutes to the hour – three minutes to at weekends – allowing the station to play music when other radio stations were breaking for news.

There were feature programmes (Grapevine/Hallam Forum) and there were home-produced dramas like the five episodes of Dying for a Drink (1978) and Down to Earth – a story of coal and colliers (1979).

But things could not last.

“Roger Moffat had his ups and downs and in one of them he lost his temper with us and he went off,” said Bill McDonald. He left Hallam in December 1981, resurfacing two years later with a Saturday morning show on BBC Radio Sheffield. “This is your last chance, Moffat. Your last ditch.” According to who you believe, the programme was phased out after a few weeks, or was it two years? Regardless, he gave up the job because of ill-health. He returned to Radio Hallam one more time, to record his obituary programme that was broadcast after his death (aged 59) in 1986. His unusual last wish was fulfilled a year later when his ashes were scattered over three far flung locations. His former colleague and friend Keith Skues helped pilot a Piper Seneca to scatter the ashes over Skye, the Channel Islands… and the Sheffield suburb of Hackenthorpe.

Bill Crozier left Hallam in 1980 and returned south where he did freelance work for the BBC, but came back to Sheffield and lived at Bradway. He died in 1994, aged 69. He was replaced on the request show by Gerry Kersey who said that “He was a very gentle broadcaster who knew the art of using silence, more than anybody I know.”

Johnny Moran switched to afternoons in the mid eighties before leaving Hallam and working briefly for Magic 828 in Leeds, and then for Classic Gold in Bradford, before disappearing completely from public view. Believed to have settled in Devon and France, he died, aged 78, in September 2022.

That leaves one survivor from those ‘rebel’ BBC DJs, and this afternoon he will take centre stage amongst former colleagues

In 1986, Radio Hallam merged with two other radio stations – Viking Radio in Hull and Bradford’s Pennine Radio – to form Yorkshire and Humberside Independent Radio (later the Yorkshire Radio Network). The stations retained their local identity but shared programmes through the evening.

Keith Skues had reportedly become disillusioned after the merger and left to take up the role of programme controller for YRN’s Classic Gold service when it launched in May 1989. The takeover by Newcastle’s Metro Radio in October 1990 ended one of commercial radio’s longest partnerships, with Bill McDonald (in charge of YRN) retiring and Skues taking temporary leave as a reservist for the RAF in the Gulf War. When he returned in December he found that he had been sacked by the new owners.

With a twist of fate, Skues presented BBC Radio Sheffield’s afternoon show in 1991, and had a brief spell back on BBC Radio 2. He moved to the BBC in the Eastern Counties in 1995 presenting a weekday late night show (loved by the late John Peel), and in semi-retirement presented the Sunday late show for fifteen years until 2020.

“When I was 19 or 20 I was in the right place at the right time and, having reached 500 editions of the Sunday show, it’s perhaps the ideal opportunity to retire.”

He said recently that the proudest moment of his career had been the creation of Radio Hallam.

In 1991, the Metro Group retired Hallam’s Hartshead studios and moved everything to the unlikeliest of locations, former brewery offices at Herries Road.

Sometime before his hasty departure, Roger Moffat had a war of words in Hallam’s offices. “Moffat, you are a has been” said a young DJ. “Yes,” he replied. “But at least I HAS been.” That conversation might now refer to Radio Hallam itself.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved