Fifty years may seem like ancient history to some. But to others, fifty years is well within living memory. In 1972, The Guardian published a special report on Sheffield.

A city on the brink of change,” was how city-based writer, G.R. Adams, described Sheffield, but has it really altered half a century later?

Let’s go back in time to see what the writer said: –

“Before this article was published, I was believed to be a true son of Sheffield. I could appear knowledgeable about goits, leats, ingots, and lady buffers. I would examine cutlery with discreet ostentation in foreign dining rooms. I had cultivated a modest paranoia about Leeds and took no interest in the affairs of Manchester or Birmingham. But now I must confess that I was not born in Sheffield, not even in Yorkshire, but in Sussex. I can therefore look at Sheffield with some detachment.

“The truth is that nothing very much has ever happened in this city. There have been no great confrontations between kings and princes, no epoch-making political drama; no great painting, literature, or music has ever been inspired in this neck of the woods. The city only rose to prominence during the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century. While great events were happening elsewhere, Sheffield was producing the iron and steel sinews which made those events possible – the expansion of railways, bridges, harbours, and industrial machinery. Two World Wars were fought with iron ships, steel tanks, and armaments. Statesmen who took part in the great debates of history looked over their shoulders to Sheffield for the means to carry out their grand designs.”

A fair assessment, but ‘great music’ did emerge from Sheffield. Off the back of Thatcher’s Britain, the 1980s created an explosion of talent – Cabaret Voltaire, Human League, ABC, Heaven 17, Deff Leppard – and the days of Jarvis Cocker, Pulp, and the Arctic Monkeys, came later. These musicians inspired a generation like me.

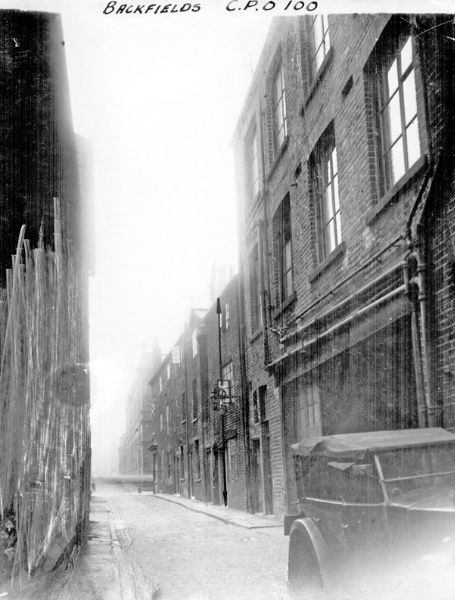

“The foundation of this fame lies in the industrial Don Valley,” wrote Adams. “Attercliffe is still an appalling place of mean-spirited houses of grey slate on blackened brick and open back yard privies. All are crowded around and overshadowed by the black hulks of dying industrial buildings. Many of the houses have been pulled down but enough remain to house many of the immigrant families and those below the poverty line. The road to Wigan Pier ran through these terrible streets. They are the conscience of the city and while one child lives in this wasteland, no councillor or citizen can sleep at peace.

“This is the spur of the great rehousing programmes that the city has undertaken. Between the wars, the extensive Manor, and Firth Park estates were built. At that time, they were sufficiently better than Attercliffe to be acceptable as an improvement, but now they are joyless graveyards of houses which will require replacement to higher standards.”

What can we say about Attercliffe? Since the article was written, the houses disappeared, and so did industry. The World Student Games in 1991 promised the great revival. Much was bulldozed, and Sheffield Arena and Don Valley Stadium were built, but even the latter wouldn’t survive. Ever since, Attercliffe has remained a lost cause, a sorry link between the city centre and Meadowhall, and a down-at-heel suburb that laments the golden days. And, while the people have returned to the city’s other old residential districts, it could be that after all this time, Attercliffe might finally become Sheffield’s next regeneration model.

In the interim, the Manor estate attracted unwanted publicity, the subject of a miserable TV documentary, but it eventually went the same way as Attercliffe. Widespread clearance and swathes of empty land appeared, but new builds have slowly brought the area back to life. Alas, Firth Park remained much the same, and is probably still suffering.

Back in 1972, Park Hill came under scrutiny, but even the writer could not have anticipated that the flats complex would be listed before suffering its unglamorous decline. Had it not been listed, it might not have risen, phoenix-like, into a citadel for young professionals, and still in the process of emerging from its slumber.

“Park Hill is a city within a city and dominates the Sheaf Valley like a castle above a moat. A second generation of families no longer remember the bitter controversy of its birth and the endless social surveys. Banks of trees and grass now cover the scars of the railway slopes and cuttings. Few grandparents now recall the previous squalor and degradation, where the Mooney gang dominated the sordid streets with razor and terror and Charlie Peace crept out at night.”

Those grandparents are long-dead, and their grandchildren are now grandparents themselves, and probably live in the suburbs watching the unrelenting spread of Sheffield’s two universities.

“On the hill, some of the best buildings in the city have been commissioned by the university. They still remain largely unrelated to each other, but the recently completed spacious underpass beneath a major road linking two parts of the campus is an imaginative solution.

“In the valley, the metamorphosis is taking the place of the Polytechnic from the chrysalis of the old Technical College. The span and complexity of its spreading wings are being watched with awe.”

The University of Sheffield advanced towards the city centre, absorbing houses, factories, churches, as well as the Jessops Hospital for Women, and almost the entire area around it. It grew to become one of Sheffield’s biggest employers, creating space-age buildings, and made the city appear incredibly cosmopolitan.

Now it is the turn of Sheffield Hallam University, the former Polytechnic, with aspirations to flatten and recreate former manufacturing areas and provide a welcoming gateway to the city.

“The new Crucible Theatre is an exciting building with its foyers painted so costly gay. It could be a place of real artistic achievement if the city will support it.”

The city didn’t support it, at least not in the beginning, but far from being the ‘white elephant,’ it was saved by snooker and then by the very thing it was built for – drama, musicals, shows, and pantomimes. The Crucible’s been joined by the Lyceum Theatre, empty and redundant in 1972, and is regarded by critics as the best producing-house outside London. Its foyers painted so costly ‘gay’ resonate with its recent multi-million pound success story – Everybody’s Talking About Jamie – doing good business in the West End and made into an Amazon film. Try explaining Amazon to our seventies’ forebears.

“There are many fine buildings of power and character in the city but few of real grace and elegance. There is no building or civic space which can make the heart gasp or the spirit sing.”

And this has been the case ever since, but times are quickly changing, and nobody could ever have anticipated, nor waited for, the long-overdue Heart of the City redevelopment.

“But now the city is facing new challenge to its skills. There is no more land left within its past boundaries to meet the new housing, industrial, and social needs of a rising population. The major expansion of the city has been channelled into Mosborough to the south-east. Here it is planned to increase the local population by 50,000 within 15 years. It is a bold and ambitious plan, based on a series of townships of 5,000 each, linked by a grid network of roads fed from a new expressway to the heart of the city. The problems of implementing this explosive growth may have been underestimated by both the local authority and the private sector. There is concern that neither the ambitious programme nor the high environmental target standards may be reached.”

It was about this time that my parents considered buying a new house at Mosborough. I was young and the thought of moving miles away from the city sent a shiver through me. But Mosborough wasn’t that far away, and the move never happened, at least not until the 1980s. By this time, previously unknown names emerged, and wrapped themselves into city history – Owlthorpe, Waterthorpe, Westfield, Holbrook, and Sothall – becoming extensions to existing suburbs like Hackenthorpe, Beighton and Halfway. And along came Crystal Peaks, Drakehouse, and, of course, Supertram.

G.R. Adams failed to mention in 1972 that there was a flaw to this masterplan. Much of this district was farmland, the border between the West Riding of Yorkshire and Derbyshire, to the south of Hackenthorpe, where most of the townships were planned. All was not lost, because those parts of Derbyshire soon found themselves in a new county.

“Local government reform will create a new South Yorkshire metropolitan county with four constituent districts of Barnsley, Doncaster, Rotherham, and Sheffield. Each of these proud cities (sic) faces similar problems of industrial waste and neglect, substandard housing, and declining industry. Sheffield as the largest centre will have considerable influence. Yet while preoccupied with Mosborough to the south-east, it must offer cooperation and coordination to the north and may have to divert resources.

“The whole of South Yorkshire is increasingly dominant by the large, nationalised undertakings for coal, steel, rail, gas, and electricity, and larger but fewer organisations concerned with major heavy engineering. The power of decision is moving away from South Yorkshire and the control of its destiny is slipping into other hands.

“While there are great financial advantages in the whole area being designated an intermediate area, it is a blow to the independent spirit of Sheffield that it can no longer stand alone upon its own excellence.

“Perhaps the most difficult task for the city is to avoid being misled by its own pride and to recognise its own deficiencies. It must create a major change in its industrial future and encourage a rich creative diversity in its life and leisure.”

And while there will be critics of Sheffield’s progress over fifty years, it could be said that the city did re-invent itself. With little heavy industry remaining, the emphasis has switched towards leisure, service industries, and something that could never have been envisaged, a digital future.

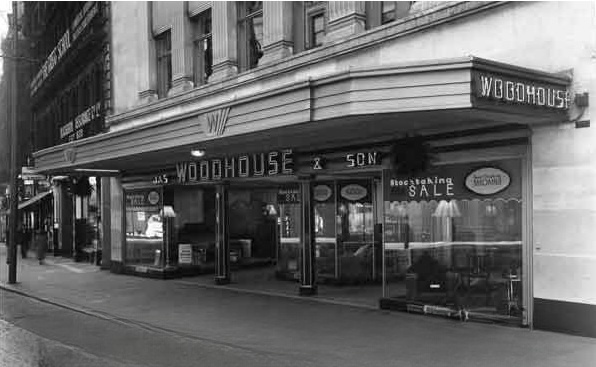

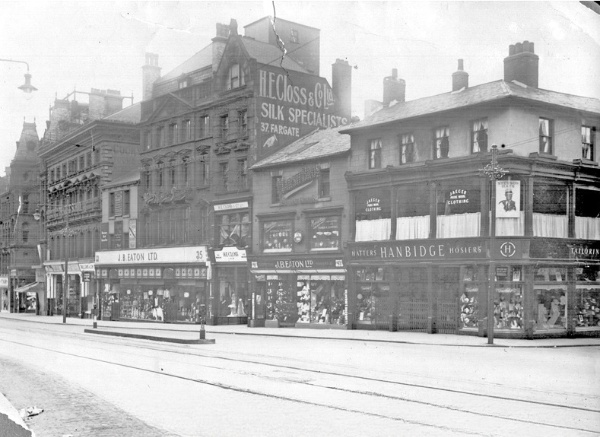

As we reflect on our city of long ago, we must touch on the astonishing decline of the city centre.

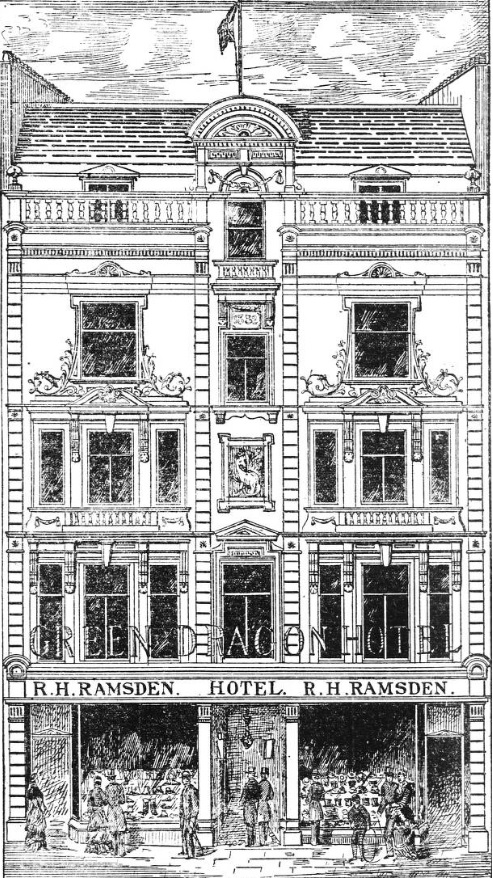

Nobody anticipated that Sheffield, with a city centre full of shops and people, would fall victim to Meadowhall and the internet. Who could have anticipated a city without Cole Brothers, Walsh’s, Cockayne’s, and Paulden’s (which would become Debenhams a year later)?

Sheffield is still changing, perhaps quicker than most other cities, and the two stages of the Heart of the City redevelopment, might be the much-needed catalyst to reinvent the city centre’s future.