The year is 1917 and Maximilian Lindlar is feeling annoyed. He had decided to sue Herbert Sinclair, editor of The Piano Maker, and its printers, King and Jarrott, for damages for an alleged libel contained in an issue of the paper.

Lindlar, born in Dusseldorf, left Germany at an early age, and had lived in Britain for forty years. A naturalised Englishman, denaturalised in Germany, he was a freeman of the City of London and between 1884 and 1912 he had been in the service of Edwin Bechstein, of Johanns Strasse, piano makers of Berlin.

The Bechstein business was founded in Berlin in 1853, developing a full range of pianos that met the requirements of professional pianists, musical institutions, and private music lovers alike. In London, its distribution was centred at Bechstein Hall in Wigmore Street, with upwards of one thousand grand and upright pianos displayed in different showrooms, with over one hundred musicians engaged for teaching purposes, and over four hundred concerts held every year.

While under the employment of Bechstein, Lindlar became involved with two British companies, Arthur Wilson and Peck Ltd of Sheffield, and Hopkinson Successors Ltd of Leeds, two retailers with monopolies for selling pianos in their respective cities.

In 1915, the total capital of Arthur Wilson and Peck was £20,000; Edwin Bechstein holding £10,250 of shares and Max Lindlar possessing £1,500. Lindlar’s brother, William Ludwig, a director, was the second highest shareholder with £2,562.

When war against Germany broke out in 1914, Bechstein’s holdings had allegedly been transferred to British shareholders, but this turned out not to be the case.

Lindlar had taken offence that Sinclair had published a scathing article and had dragged up comments made by him in preceding years.

“It is a national impossibility for an Englishman to produce a piano with each note perfectly balanced in tone. He has no true ear. His piano sounds all right to him, he does not know.”

Sinclair also published comments that Lindlar had made about the war.

“I do not think that England will be able to hold out financially to the end as Germany is very strong and well organised.”

What irked Lindlar most was a story in a newspaper that claimed he was attempting to drive British officers out of London’s German Athenaeum Club.

Such was the controversy over Arthur Wilson Peck and Co’s German influence that it was discussed in Parliament and subject to investigation by the Board of Trade in 1916.

Lindlar won his case and was awarded one farthing in damages, but Arthur Wilson Peck and Co suffered, its name ‘MUD in large letters’ according to one journal while others continued to call it a ‘German’ company. Soon afterwards, Edwin Bechstein’s shares were sold to a British businessman and the Lindlar brothers held a dinner at Sheffield’s Grand Hotel to announce that their interests had also been sold and were retiring from the business.

Afterwards, it was business as usual for Arthur Wilson and Peck Ltd, a Sheffield company that grew out of Victorian enthusiasm for the piano.

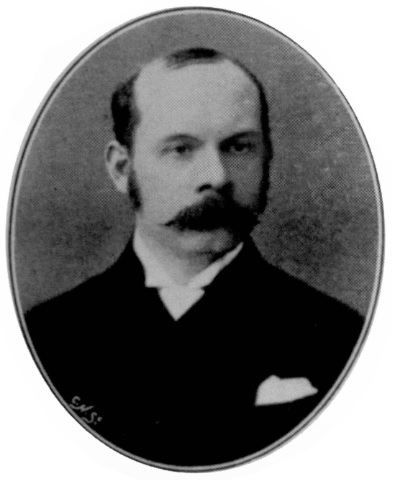

The company was created after Max Lindlar had masterminded the merger of two successful Sheffield piano sellers, Arthur Wilson, and John Peck, in 1892.

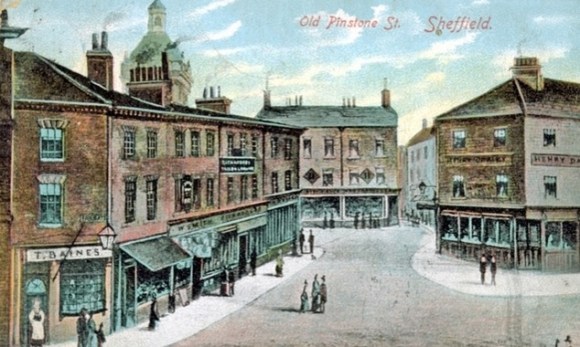

Arthur Wilson had started out as a piano shop at the corner of York Street before moving to Fargate and West Street, while John Peck, a piano tuner, had a business at the County Piano Saloon on Church Street (situated in the Gladstone Building).

The story behind Arthur Wilson is a strange one because the name was a pseudonym created to disguise the identity of the shop’s real owner.

He was Henry Charles Brooklyn Mushet (1845-1923) from Belgrove House, Cheltenham, the son of Robert Forester Mushet, the inventor of ‘Mushet’ steel, a self-hardening steel, who came to Sheffield with his brother Edward in 1871 to supervise the manufacture of ‘Mushet’ steel at Samuel Osborne and Co, Clyde Steel Works, on The Wicker. A music lover, he set up Arthur Wilson as a side line in 1878 and became an agency for Bechstein Pianos, where he met Max Lindlar.

John Peck (1841-1922) was born in Blyth, near Worksop, and was also regarded as the “father of the city’s fiddlers,’ his skills as a violinist surpassing those of the ‘stars’ who visited Sheffield and a man who went on to become a successful conductor.

With Max Lindlar’s connection to Bechstein Pianos it was decided to form Arthur Wilson, Peck and Co Ltd in 1892. With capital worth £20,000, Lindlar became chairman and John Peck joined as a director, but Mushet decided to step down from the business. Other notable appointments were William Cole, another piano dealer, who served as Managing Director for the first year and C.D. Leng, son of newspaper publisher William Christopher Leng, and a partner in the Sheffield Telegraph.

The first task for the new company was to close its three shops on West Street, Fargate, and Church Street, and consolidate its business in premises vacated by Hepworth Tailor’s at the corner of Pinstone Street and Barker’s Pool. It had cost £470 to set up the company and convert the building into ‘Beethoven House’.

Within months, Max had been joined by his brother, William Ludwig Lindlar, who had intended to follow in the footsteps of their father, the landscape painter J.W. Lindlar. Instead, he assumed musical and commercial work, and would eventually become vice-president of the Music Trades Association of Great Britain. He became managing director in 1894 and was responsible for organising important concerts in Sheffield and Nottingham, where the company had established a second store.

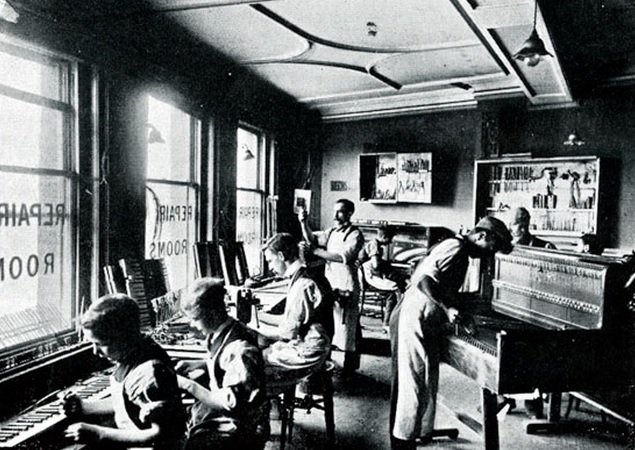

They were described as pianoforte, harmonium and American organ merchants, tuners, and repairers, as well as sole agents for Bechstein pianos. Within the Pinstone Street building it also had a concert hall used for concerts and recitals.

In 1905, Wilson Peck moved to the opposite corner of Barker’s Pool in the former premises of Appleyards and Johnson, cabinet makers. It was described as ‘the best equipped premises outside London’ and the replacement Beethoven House is the building that most of us still remember.

Wilson Peck were famous for selling musical instruments, sheet music, hosting concerts, and selling ‘new’ phonographic records. On its upper floors it had rooms that could be used for tutors to teach music. In later years it developed a thriving business selling concert tickets for the City Hall and other venues across the country. Wilson Peck ended up with Sheffield’s oldest record department (memorable for its soundproofed listening booths) with sales of records accounting for a sizeable proportion of its business.

Shares in the business changed hands following the departure of the Lindlar brothers and at one stage its chairman was B. J. Readman, who also happened to be chairman of John Brinsmead & Sons, one of England’s premier piano makers. Additional branches soon followed on London Road and Ecclesall Road.

A 1956 advert claims the shop to be ‘the place to go for everything musical: Pianos, Television, Radio, Radiograms, Records, Concert Tickets, etc.’

Wilson Peck was held in high esteem, and it is hard to determine when its decline began. Two World Wars didn’t help a niche market, and the Victorian ideal of making music at home, when pianos were a common sight, had disappeared by the early twentieth century, having a devastating effect on sales of musical instruments and sheet music.

By the 1970s, the directors at Wilson Peck had diversified into property investment culminating in several subsidiary companies and ownership of buildings across the UK. Originally known as the Wilson Peck Group, it changed its name in the 1980s to Sheafbank Properrty Trust, subsequently becoming UK Estates.

The retailing demise came in the 1980s when Sheffield City Hall decided to take its ticket sales in-house, and the emergence of national record chains (HMV, Virgin Records, Our Price etc.) eroded into Wilson Peck’s earnings.

In 1988, the company vacated Beethoven House, and H.L. Brown, jewellers, moved in. Wilson and Peck downsized to premises on Rockingham Gate but that proved short lived. I’m led to believe that Wilson Peck ended up in ‘an end-of-terrace’ corner shop on Abbeydale Road that closed in 2001.

NOTE: –

During the Parliamentary discussion about Arthur Wilson, Peck and Co in 1916, it was said that they also owned a business called Hilton and Company. There is no trace of this business, not helped because Wilson and Peck didn’t retain its archives.

However, there is a post from 2015 on the UK Piano Page whereby somebody said that they had bought an old upright piano: –

“The piano has ‘Hilton & Co’ written in gold writing in the centre of the key cover, also it has ‘Wilson Peck, Fargate, Sheffield’ written on it on the right hand side of the key cover.”

There was a Yorkshire piano company called Hilton and Hilton, but this piano appears not to have been manufactured by them.

Was Hilton and Co a brief attempt by Arthur Wilson, Peck and Co to sell its own manufactured pianos? Somebody, somewhere, might have the answer.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.