The hoardings are up, contractors are in, and Nos. 30-42 Pinstone Street (as well as Palatine Chambers), are about to be resurrected as part of a Victorian frontage to a brand-new Radisson Blu Hotel. The old facades will remain, but everything behind it, including Barker’s Pool House, on Burgess Street, will be demolished and rebuilt.

Until the 18th century, Pinstone Lane (as it was called) crossed fields and rough grazing land. As Sheffield grew, it became a twisting, close, and sinister-looking passage. In 1875, Sheffield started a street widening programme, and Pinstone Lane was transformed into a 60ft wide thoroughfare to match the magnificence of the proposed new Town Hall.

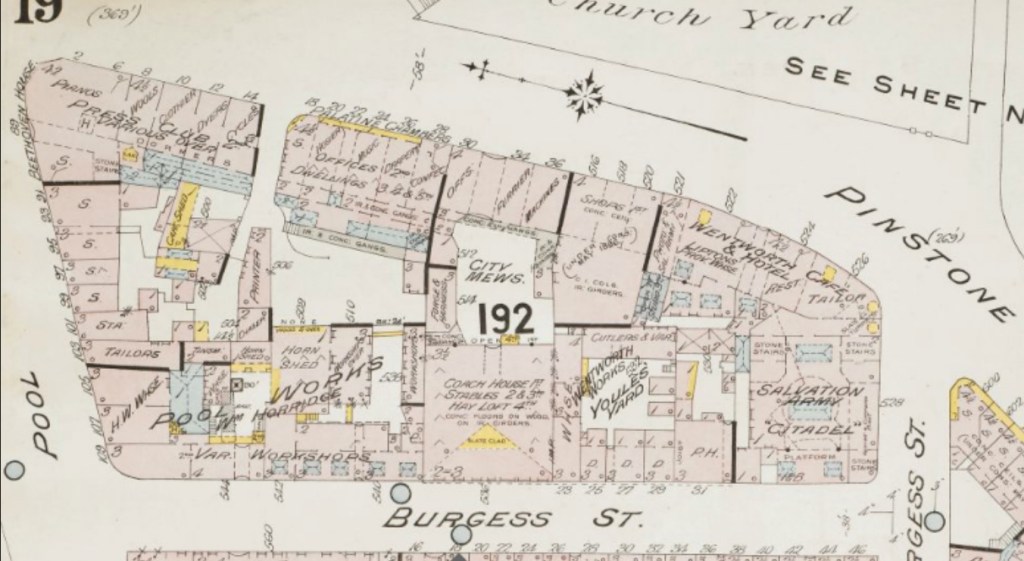

In 1892, Reuben Thompson, of Glossop Road, an established operator of horse-drawn omnibuses, cabs, and funeral director, gave up his lease on premises at Union Street, and purchased a plot of vacant land opposite St. Paul’s Church (now Peace Gardens) from the Improvement Committee, along with adjoining property at the back towards Burgess Street.

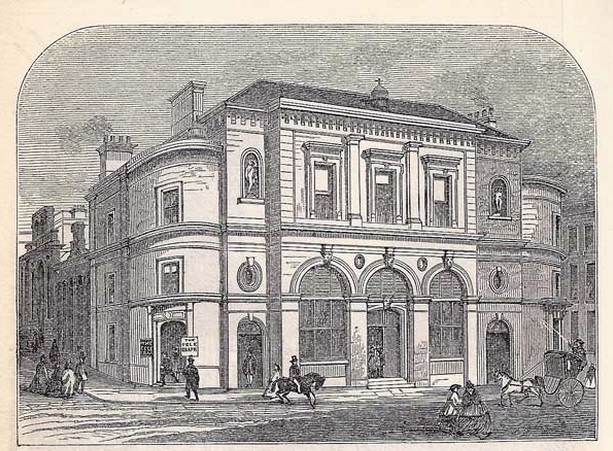

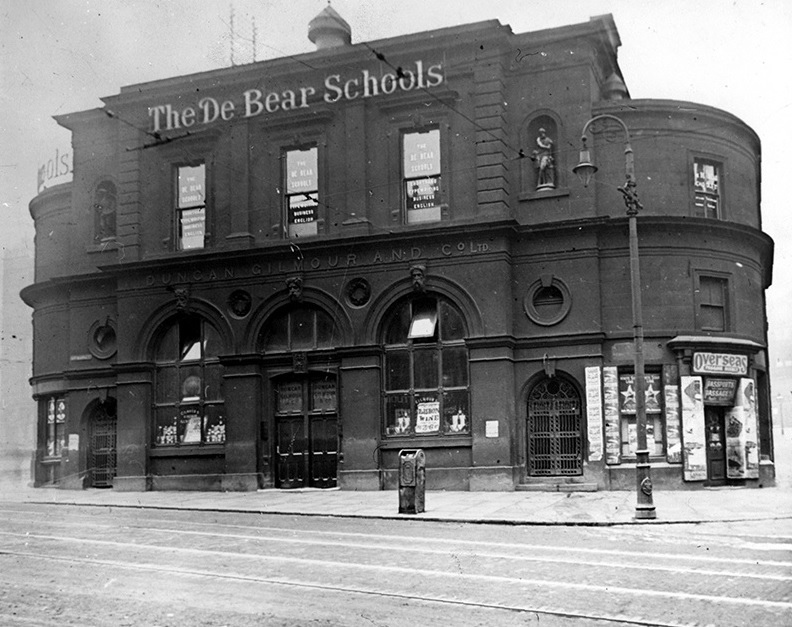

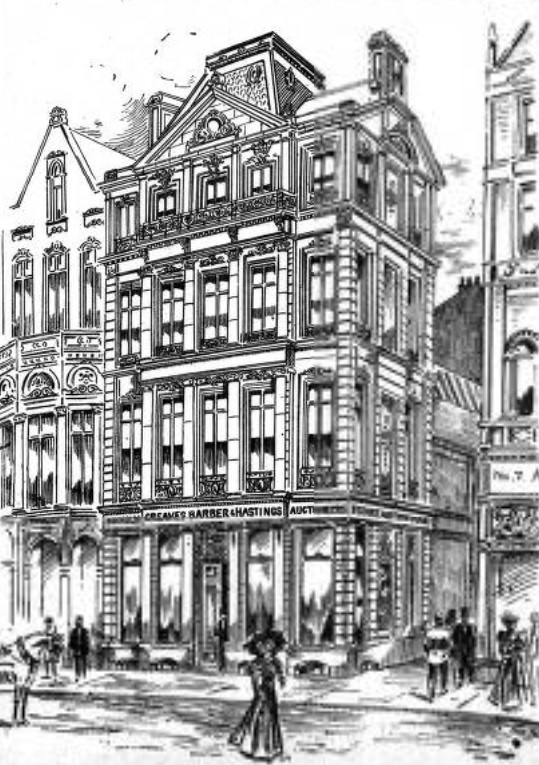

The Salvation Army had already started building its Citadel on Cross Burgess Street as well as three large business premises at its corner with Pinstone Street. Thompson bought the land alongside this, and employed Flockton, Gibbs, and Flockton to design a red brick building, with handsome stone dressings, comprising ground floor shops, and offices and flats above.

In 1895, he purchased an additional plot of land to build three additional shops. This extended the length of the original building and incorporated an entrance tunnel from Pinstone Street through to stabling and carriage sheds behind, the carriages lifted from floor to floor by a hoist.

It extended the range to fifteen bays, and across the top of the building ran an enormous sign – ‘Reuben Thompson’s City Mews – and was completed in time for the opening of the new Town Hall.

This is the building we still see, although the advent of the motor car, and high petrol prices during the 1930s, saw Reuben Thompson Ltd vacate a property that had become far too big. It consolidated on Glossop Road and Queen’s Road and focused on its funeral business.

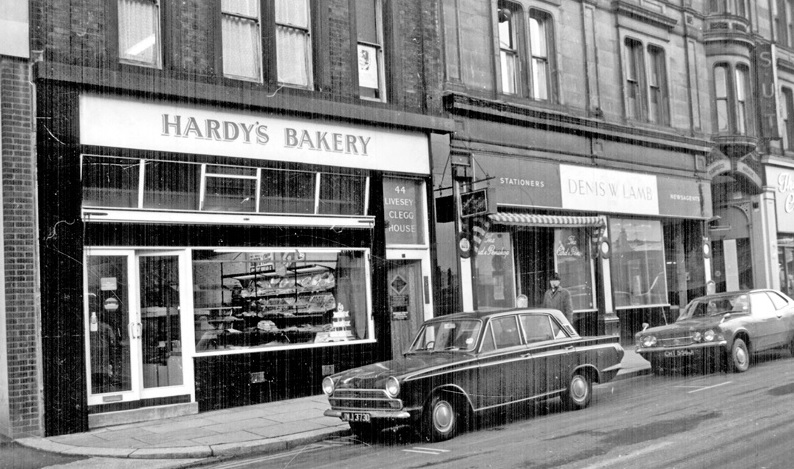

Those of a certain age will be familiar with the shops that have occupied this prime location on one of Sheffield’s most prestigious streets.

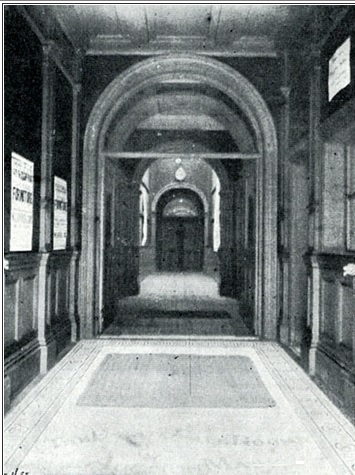

The Pinstone Street entrance to City Mews, where horses and carriages once passed, was filled-in, and later lost in the frontage of Mac Market (later to become International, Gateway, Somerfield, Co-op, Budgens, and finally, as a temporary home for WH Smiths).

The construction of Barker’s Pool House on Burgess Street in 1969-1970 (on the site of the former stabling and carriage-houses) linked both properties and altered much of the original Pinstone Street interiors. These too will be lost in the latest stage of the Heart of the City II redevelopment.

© 2021 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.