Our final instalment about hidden tunnels underneath Sheffield takes us to 1936, when Frank H. Brindley investigated a tunnel found by workmen underneath the offices of the Telegraph and Star newspaper at Hartshead.

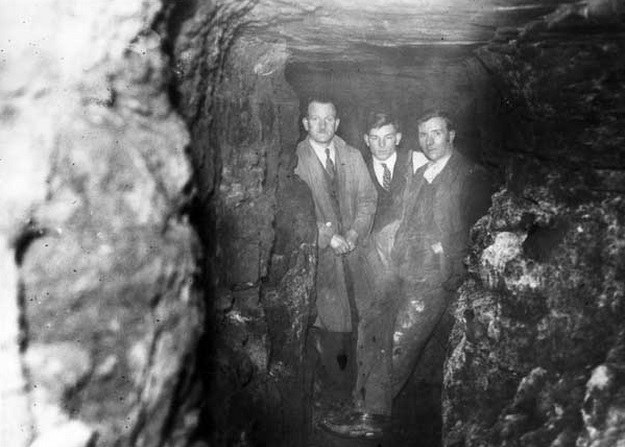

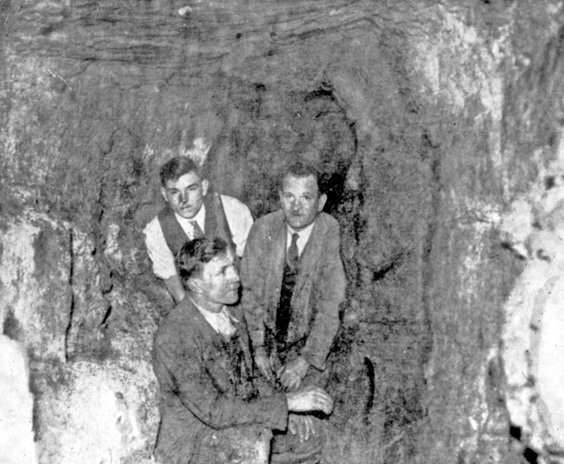

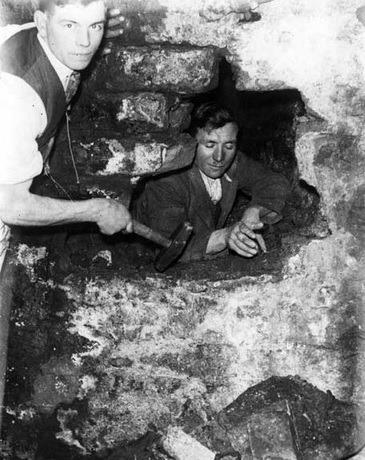

Brindley explored the opening using two skilled masons. The floor was described as well-worn as from long usage, and bone dry, without any trace of rubbish.

“The tunnel was cut from solid rock, about six foot in height and five to six feet wide. Its first direction was east, taking a line towards Castle Hill.

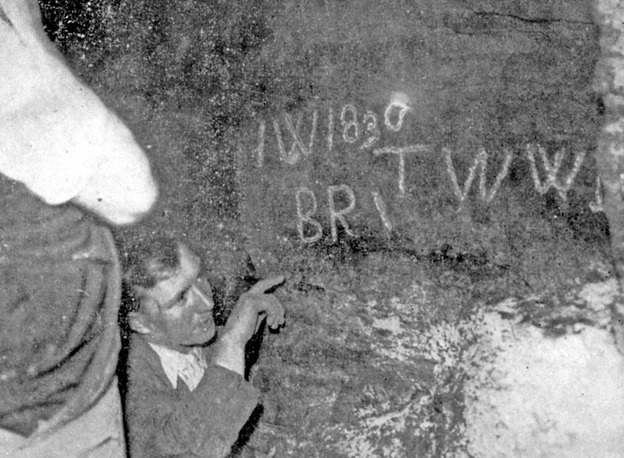

“It turned slightly south and then resumed its eastern direction, and when 50 foot from the entrance hall, we found the first trace of others having found this mystery tunnel before.

“On one of the rock walls were the following letters ‘I.W. 1830’ then just below ‘B.R.’, a dash and then ‘T.W.W.B.'”

Exploring further, they passed beyond High Street and after rounding several bends found the tunnel ended abruptly at a brick wall, probably the foundations of a building in King Street.

If the wall hadn’t been built, they would have been able to walk underneath the buildings of King Street and entered what was once Sheffield Castle at a point where the markets were then situated.

Pictures and an interview were published in the Yorkshire Telegraph and Star in 1936, providing clear proof of their existence.

Brindley concluded that this was the missing tunnel from Sheffield Castle to the Parish Church (now Sheffield Cathedral), and was undoubtedly the one that had been uncovered in 1896, when Cockayne’s were excavating for a new store on Angel Street, which had then been dismissed as a sewer.

Mr Brindley was in the headlines again at the start of World War Two, when he placed details of underground passageways at the disposal of Sheffield’s Air Raid Precautions (ARP) authorities.

He explained that over the years, tunnels had repeatedly been found cut in the sandstone. Some appeared to have been old colliery workings, but many couldn’t be explained, while many appeared to radiate from the site of Sheffield Castle and were probably connected to mansions in the neighbourhood.

Brindley also shed further light on the 80ft shaft he’d found at Hartshead, that headed towards High Street.

The shaft had led to another tunnel running under Fargate, towards Norfolk Row. Unfortunately, explorations had come to an end when one of the investigating party was overcome by fumes only 50ft from the bottom of the shaft.

This time, Mr Brindley elaborated that the tunnel was part of a network that also connected Sheffield Castle with Manor Lodge.

It’s hard to believe now, but the hillside in Pond Street was said to be honeycombed with coal workings, but Brindley claimed that there were two other “mystery” tunnels found.

One section running from a cellar at the Old Queen’s Head Hotel, he said, was found when Pond Street Bus Station was being built during the 1930s, and the other was found near the top of Seymour Street (wherever that might have been). Beginning in an old cellar it ran beneath the site of the Royal Theatre, towards the Town Hall, where it was lost.

As far as I am aware, this was the last occasion that these tunnels were explored, probably sealed up but still hidden underneath the city centre.

We’ll end these posts as we began by saying that – “One day soon, Sheffield Castle might give up some of its secrets.”