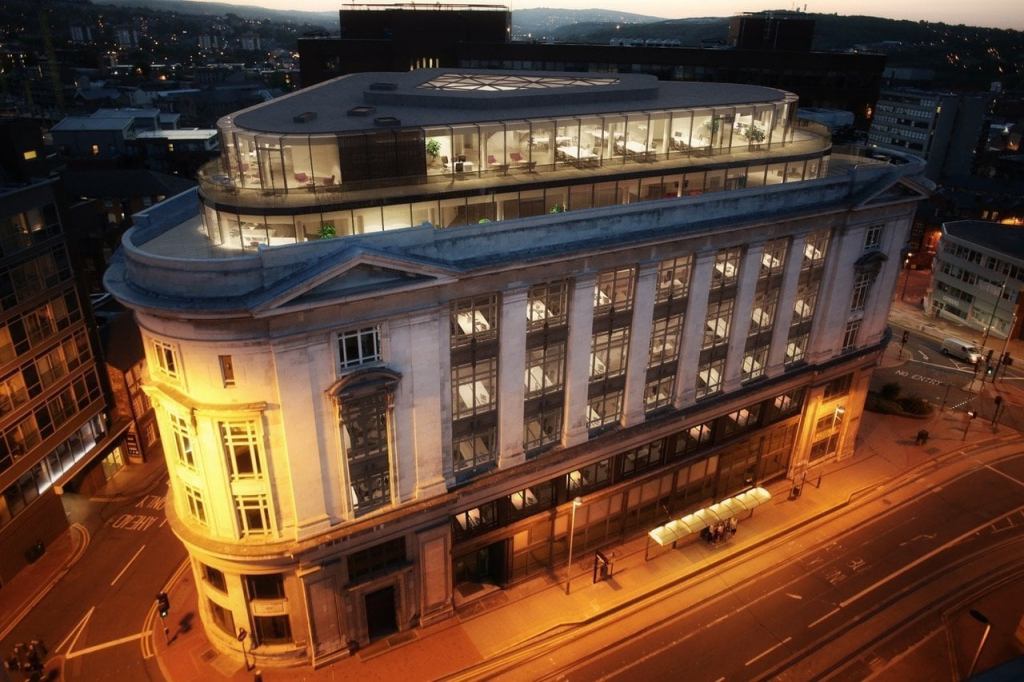

Let’s not dwell too much on the recent history of the Stone House pub on Church Street. Famous in the seventies and eighties as the must-go-to bar on a Saturday night, and memorable for the courtyard that gave you the impression that you were standing underneath a star-filled sky.

The courtyard disappeared in the 1980s after the building of Orchard Square, the Stone House refurbished as a trendy establishment that lasted until 2005.

It was bought by the owners of Orchard Square, London & Associated Properties, for £2.5million, space given for the expansion of T.K. Maxx, and the older, listed part, left empty.

It’s a sad time for this Grade II-listed building, seemingly unloved, and not likely to attract a new tenant soon.

There is some confusion as to the date when the Stone House was built.

A band inscribed across the front states “1795, White & Sons, late Thomas Aldam.” But, the two-storey building we see today dates from the 1840s.

Over the doors, round-arched panels are inscribed with “The Stone House” and “Private Lodgings.”

Thomas Aldam, an importer of wines and spirits, moved here in the 1840s, continuing until his death in 1858.

The business was taken over by Dunkelspiehl Brothers & Company in 1867, trading from the site until the late 1870s.

The business transferred to J.B. White and Sons; an old Chesterfield company that had been established in 1795 (hence the date seen on the building today).

The name of the Stone House first appeared in 1913 following the acquisition of J.B. White and another Sheffield wine merchant, William Favell and Company, by brewer Duncan Gilmour and Company.

The two companies became White Favell and Company, wines and spirits merchants and cigar importers, operating in the front of the building. More importantly, the rest of the building became the Stone House public house.

White Favell and Company was later run by J. Lomax Cockayne, the managing partner in what became White, Favell and Cockayne.

Duncan Gilmour and Company was taken over by Leeds-based Tetleys in 1954, the wines and spirits business gradually being phased out and part of its old windowed frontage bricked up.

An illustrious past for the building, now waiting for a new lease of life.