The next time you settle into a seat at one of our multiplex cinemas, take a moment to consider that there are still traces of Sheffield’s original cinema.

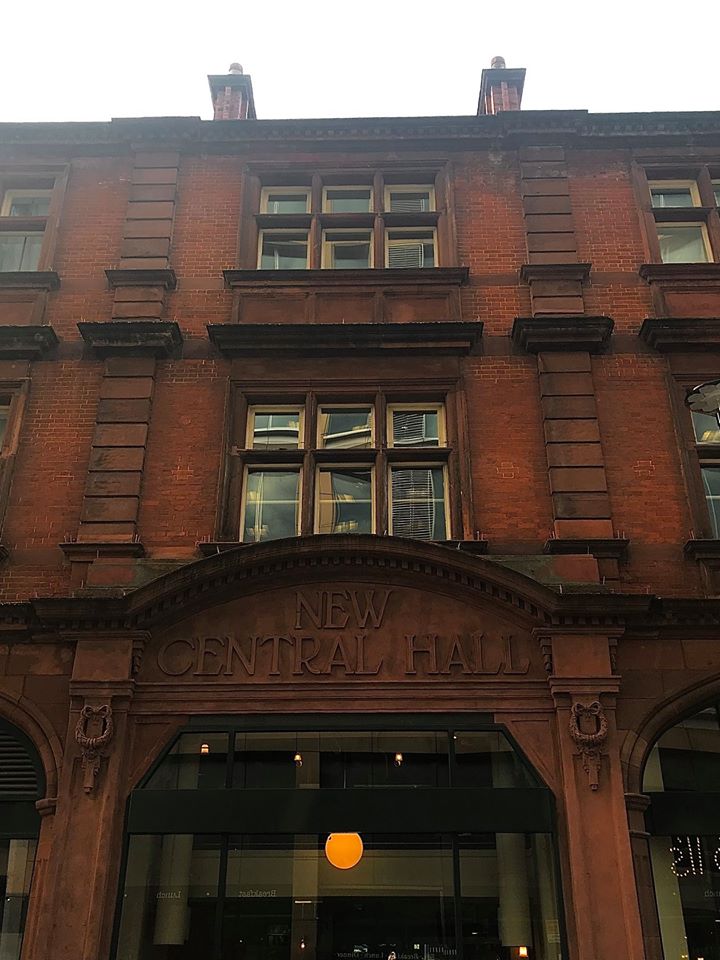

Head down to Norfolk Street, and look at part of Brown’s Brasserie and Bar. Above one of the plate glass windows is the name New Central Hall, the remains of a former decorative arched entrance.

This part of the building, just around the corner from St. Paul’s Parade, was built in 1899 by architect John Dodsley Webster as the Central Hall for the Sheffield Workmen’s Mission, established by Pastor A.S.O. Birch in 1880 at the old Circus on Tudor Street. (The building was constructed by James Fidler, contractor, of Savile Street).

The cost, exclusive of land, was about £4,000, made possible by a £3,500 loan from Mr F.E. Smith, “trusting those who will attend the hall to repay him when they can.”

The Central Hall had a frontage of 46 feet, the ground and first floors devoted to the main hall, which contained a gallery, and seating accommodation for 500 people. The second floor was occupied by five classrooms and an office, while the basement was taken up by a large kitchen and store-rooms.

It had been designed as a place of public worship; the Mission having previously held services at the Montgomery Hall on Surrey Street and opened in December 1899.

However, no sooner had it opened when, somewhat unexplainable, the Workmen’s Mission left and taken up residence at the Albert Hall in Barker’s Pool.

It was left to John Dodsley Webster to advertise the Central Hall as being available to buy or let on lease, “suitable for conversion to offices, flats or business premises.”

It wasn’t until November 1904 that we find evidence that the building was in use again.

Nelsons Ltd, “The Pensions Tea Men,” advertised that it was opening its drapery, ready made clothing and boot and shoe departments at Central Hall. It was another short-lived scheme, because in March 1905, the shop had gone into liquidation.

Nonetheless, there was somebody waiting in the wings who saw Central Hall as a long-term answer to a conundrum.

Henry Jasper Redfern (1871-1928) is almost forgotten now, but he packed a lot into a relatively short life. Here was a man who had made a fortune with a long list of business successes – “optician, refractionist, manufacturer of optical, photographic and scientific instruments, photographer, expert in animated photography and Rontgen rays, electrician and public entertainment.”

Born in Sheffield, Redfern trained as an optician, opened a business on Surrey Street, and later added a photography shop nearby.

However, he was more famous in the realms of cinematography, a subject he studied in its early stages, and became a pioneer in exhibiting moving pictures.

Alongside his daily routine, he toured the country with “Jasper Redfern’s world-renowned animated pictures and grand vaudeville entertainment” show.

Redfern decided that a permanent venue was required, and Central Hall provided a convenient solution.

In July 1905, New Central Hall opened to great flourish with the showing of the “Royal visit to Sheffield in its entirety,” shown twice nightly, along with a complete programme of live variety entertainment.

In the following months, there were screenings of more moving pictures, with titles like “Winter Pastimes in Norway” and “North Sea Fishing”, as well as resident acts, such as the two French conjuring midgets and songs by Madame McMullen and Lawrence Sidney.

New Central Hall attracted big houses twice a night, much to the dismay of Smith and Sievewright, clothiers, which occupied the shop next door, and took Redfern to court complaining that the queue of waiting patrons was detrimental to their business.

But, by 1912, the cinema was in financial difficulties, although its company secretary, Norris H. Deakin, found backing to improve amenities, increasing the size of the stage and adding a proscenium arch, and increasing seating capacity to 700.

Jasper Redfern & Company Ltd was wound up and replaced with the New Central Hall Company in early 1913, with Deakin as managing director. At what stage Jasper Redfern left is uncertain, but he emerged elsewhere in the country, his life story worthy of a separate post.

The tenancy of New Central Hall quickly passed to yet another company, Tivoli (Sheffield) Ltd, and the cinema reopened in January 1914 as the Tivoli, newly decorated and improved, with variety acts stopped a year later.

The Tivoli was a success but suffered a disastrous fire during the night in November 1927. Four fire engines raced to the scene, one using a new £3,000 ladder, and attempted to put out flames coming from the roof. However, parts of the roof were destroyed, the balcony was a charred mass, and the ground floor was a mass of burning woodwork.

The cinema was rebuilt and opened in July 1928 as the New Tivoli, completely refurbished with carpets by T. & J. Roberts of Moorhead, theatre furnishings by L.B. Lockwood & Co, Bradford, and lighting effects provided by J. Brown & Company, of Fulwood Road.

In the following decade, a Western Electric sound system was installed and because of a penchant for screening cowboy films, the New Tivoli was popularly known as “The Ranch.”

The curtain finally fell on the cinema on 12 December 1940, the result of Blitz fire damage. It was never rebuilt, the cinema area adapted for offices, restaurant and shop.

All that remains of the original Central Hall is its frontage, and the only nostalgic reminder of its cinema days being the stone-carved sign.