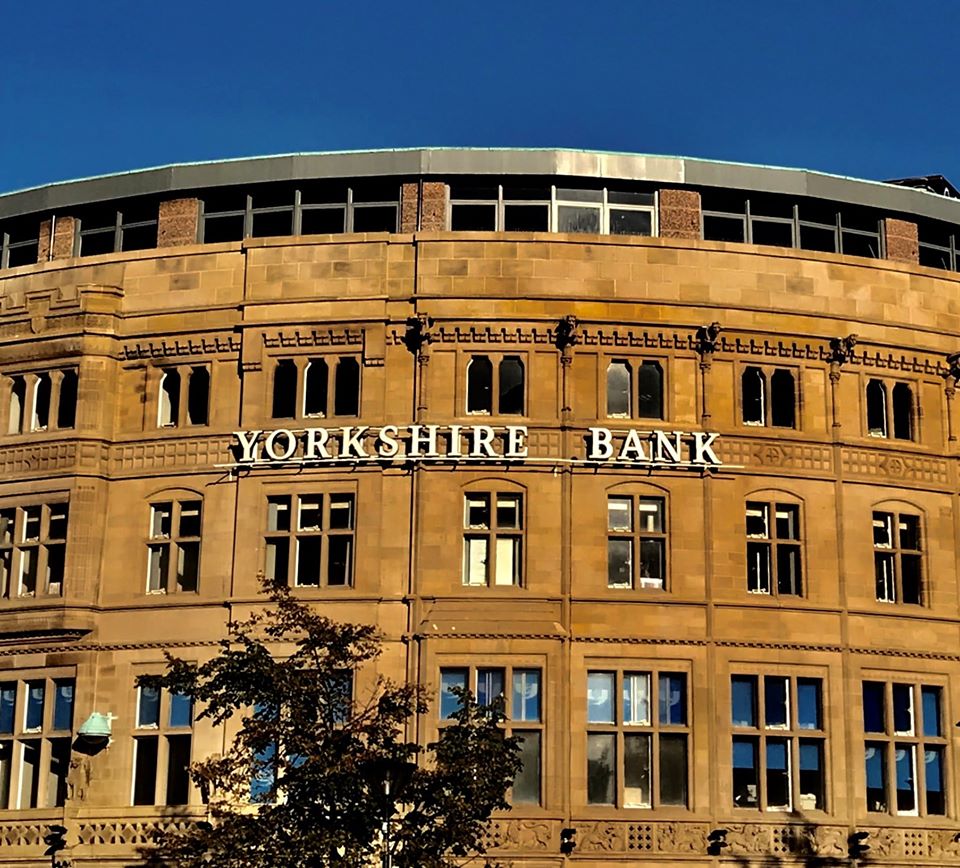

This is one of the most imposing buildings in Sheffield city centre. The Yorkshire Bank building, in late-Gothic design, with five-storeys and a long curved Holmfirth stone front, stands at the top of Fargate, nudging around the corner into Surrey Street.

With it comes a long history and a few surprises as to its former use.

In the 1880s, when a plot became available at the side of the Montgomery Hall on (New) Surrey Street, the directors of the Yorkshire Penny Savings Bank bought the land to erect a new bank.

It turned to Leeds-based architects Henry Perkin and George Bertram Bulmer who were asked to create a brilliant show of Victorian entrepreneurship.

The corner stones were laid on 18 January 1888 by builders Armitage and Hodgson of Leeds and was completed in the summer of 1889.

The Yorkshire Penny Savings Bank occupied two floors – at ground level was the large banking hall, fitted out in polished wainscot oak with a mosaic-tiled floor, the basement contained the strong-room.

Lord Lascelles, the president of the bank, officially opened it on 25 July 1889.

The remainder of the building was used as a restaurant and first-class hotel, leased by Sheffield Café Company, formed in 1877 as part of a growing movement of temperance houses throughout the country. No drink allowed here.

The Albany Hotel opened in September 1889 with electric light throughout, a restaurant, billiard room, coffee and smoking rooms, private dining rooms as well as 40 bedrooms above.

By the 1920s, the Sheffield Café Company, with multiple cafes and restaurants across the city, was struggling financially and ceased trading in 1922.

Their assets were bought by Sheffield Refreshment Houses, which operated the hotel until the 1950s.

With grander hotels nearby and with dated facilities the Albany Hotel closed in 1958.

The Yorkshire Penny Savings Bank became Yorkshire Bank in 1959 and the old hotel was converted into offices – known as Yorkshire Bank Chambers – after 1965.

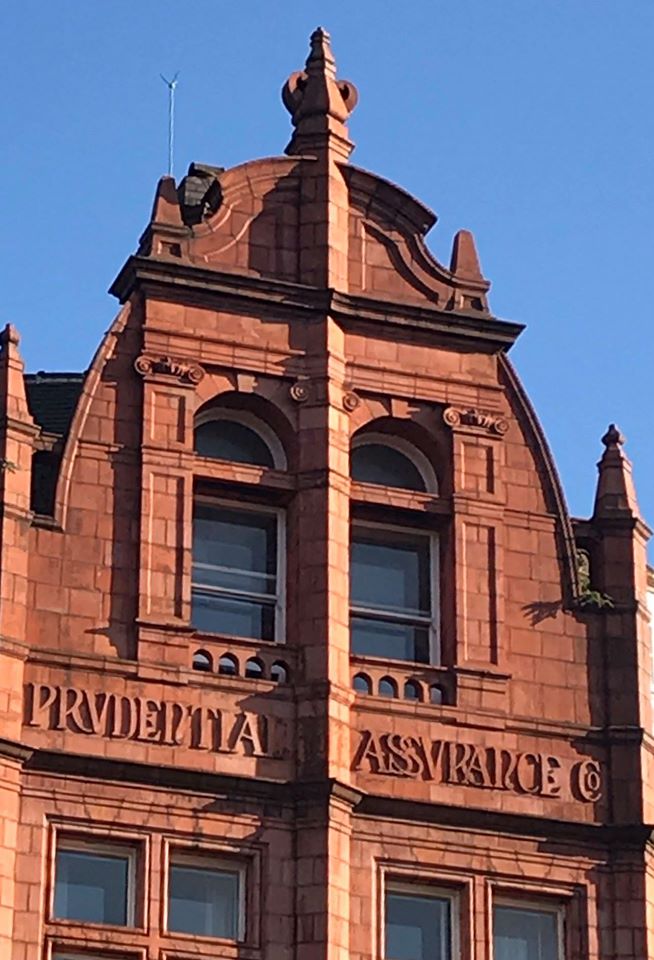

The interiors have long altered but the external appearance remains much the same, with carved winged lions, medieval figures, shields and gargoyles on the outside of the building. Gabled dormers, lofty chimneys and a crenelated parapet were sacrificed during the 1960s.