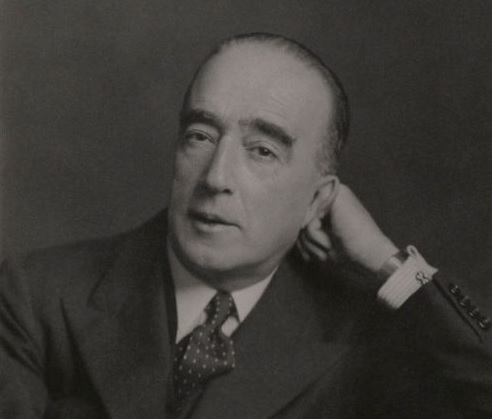

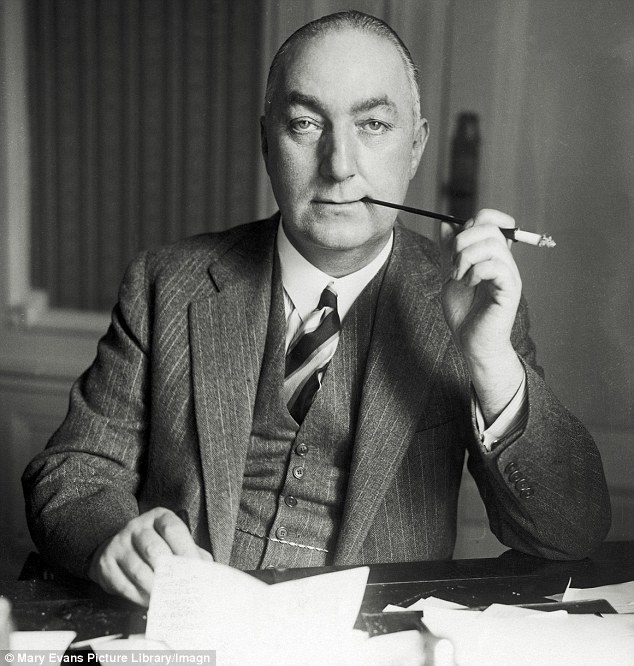

Reading a biography of Edgar Wallace is an exhausting experience. He was the author of over 170 books, translated into more than thirty languages. More films were made from his books than any other twentieth-century writer, and in the 1920s a quarter of all books read in England were written by him.

He was said to sleep just a few hours every night. The rest of the time was spent dictating novels, plays (many of which were performed at Sheffield’s Theatre Royal and Lyceum), newspaper articles, and racing tips. His secretaries typed out finished copy and sent them off to publishers.

Edgar Wallace, the illegitimate son of a travelling actress, rose from poverty in Victorian England to become the most popular author in the world and a global celebrity of his age. He scooped the signing of the Boer War peace treaty when working as a war correspondent, before achieving success as a film director and playwright. At the height of his success, he was earning a vast fortune, but the money went out as fast as it came in. Famous for his thrillers, with their fantastic plots, in many ways Wallace did not write his most exciting story: he lived it.

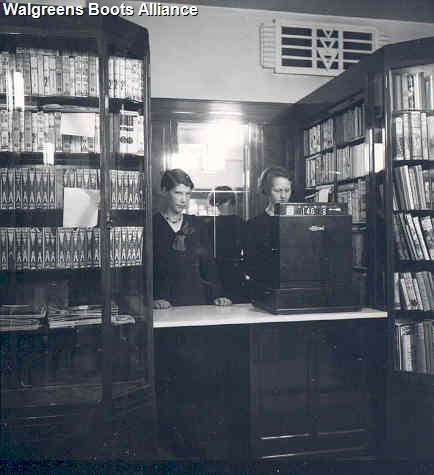

In the 1930s, Joseph P. Lamb, the Sheffield city librarian, analysed borrowing trends and decided that people wanted the same type of books – they ‘read along mass lines,’ he once said, and people were irritated when ‘their’ books were out on loan. As a result of this, books by populist authors like Edgar Wallace were purchased in fifties of each title.

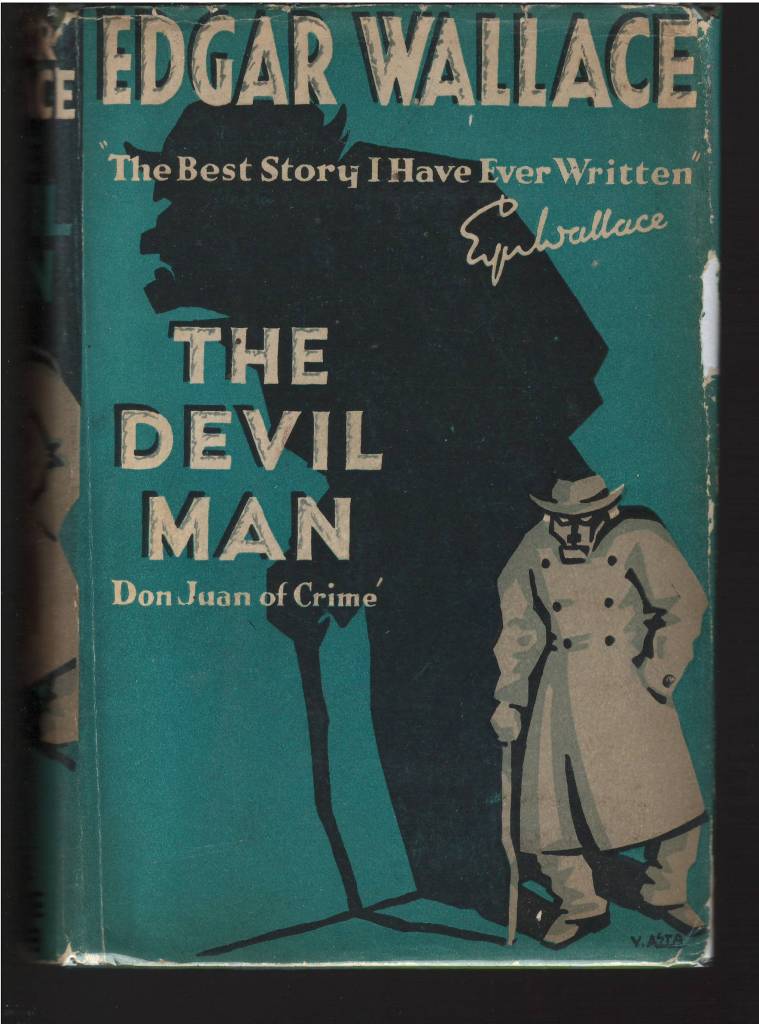

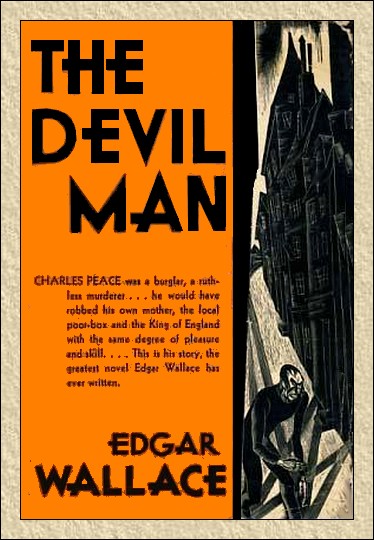

In 1931, Edgar Wallace published ‘The Devil Man,’ with definitive links to Sheffield.

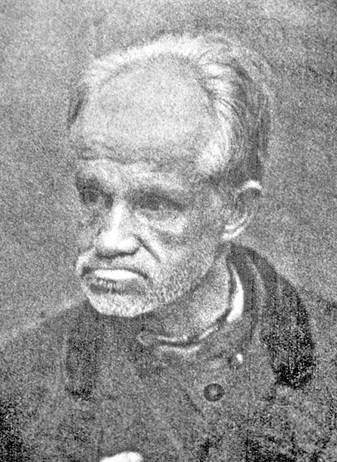

The book focused on Sheffield’s favourite criminal Charles Peace. According to the Sheffield Daily Independent it held the reader throughout. ‘The bad little man is as fascinating in Mr Wallace’s pages as he was supposed to be to women during his lifetime.’

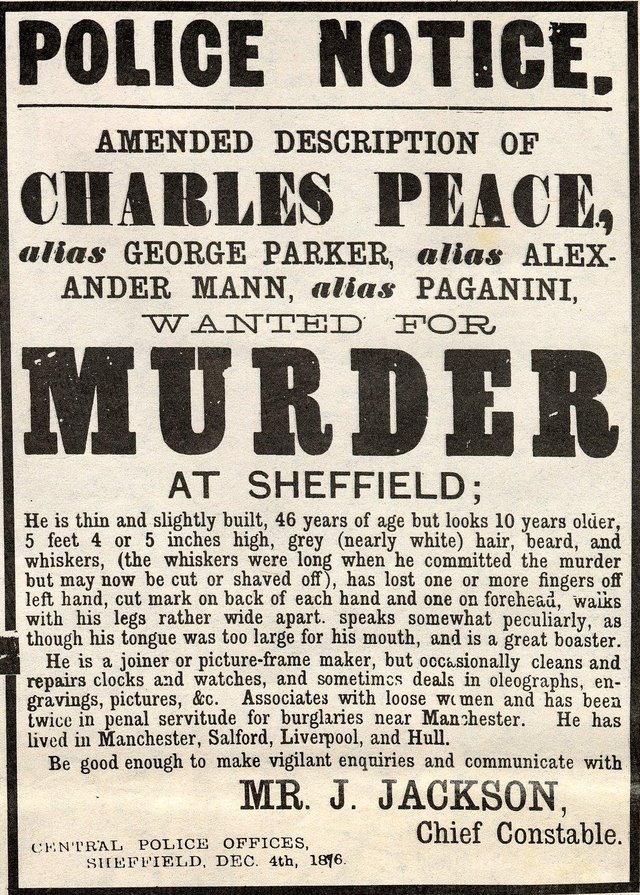

“He was a queer, incongruous figure of a man. His height could not have been more than five feet; the big, dark, deep-set eyes were the one pleasant feature in a face which was utterly repulsive. They were the eyes of an intelligent animal. The forehead was grotesquely high, running in furrows almost to where at the crown of his head, a mop of grey hair rolled back. The unshaven cheeks were cadaverous, deeply lined and hollow. He wore home-knitted mittens, and in one hand clutched an ancient violin case.”

Wallace did not mix fiction with fact, ‘he rather built an additional storey of fiction on the solid house of fact.’

Wallace raked Peace’s ugly career as it stood – his friendship with the flashy Mrs Dyson and the subsequent murder of her husband – and superimposed a strange plot regarding the secret of a new steel process – presumably stainless.

Dyson had in his possession a bottle containing some all-important crystals, and Peace is offered a large sum of money by foreigners living in Sheffield if he will steal the bottle.

This, according to Wallace, was his errand on that terrible night in Banner Cross in November 1876 when Peace shot Dyson, a former neighbour at Darnall.

Peace quarrelled with Mrs Dyson, shot her husband, secured the bottle, and then handed it to a confederate, which was the last he ever saw of it. It was in connection with this murder that, according to Wallace, Peace had previously gone to Manchester to commit a burglary and murdered a policeman.

‘The atmosphere of Sheffield in the ‘70s is deftly caught,’ said the Sheffield Daily Independent. ‘And although one feels in this book as one does in other Wallace novels – that toward the end the author has got a little bored with his subject: the story is brilliantly told.’

Wallace stated that it had taken him four years to collect the facts for the story, four months to construct the book, and four days to write it.

According to author Neil Clark, who penned ‘Stranger Than Fiction – The Life of Edgar Wallace’, ‘Sir Patrick Hastings was a guest during the weekend Wallace wrote the 70,000-word novel in just sixty hours. Hastings had difficulty in sleeping on the Friday night, and had gone to Wallace’s study where he found him dictating. He sat and watched him for two hours and was enthralled by the way Wallace worked. By nine o’clock on Monday morning, Wallace had completed his task, which earned him £4,000 in serial rights alone. He then went to bed for two days to make up for the sleep he had missed.’

A year after the novel was published, Edgar Wallace went to Hollywood to work on the RKO ‘gorilla picture’ King Kong, but his gruelling lifestyle finally caught up with him, and he died of diabetes and double pneumonia in February 1932.

In his will it was revealed that he had debts of £140,000 and almost all his possessions had to be sold. However, within two years, the royalties from Wallace’s work had cleared all the debts.

Sources: Stranger Than Fiction – The Life od Edgar Wallace, The Man Who Created King Kong, by Neil Clark (2014) and Val Hewson at The Auden Generation and After conference, Sheffield Hallam University, 17 June 2016.