Grosvenor House, home to HSBC, one of the first buildings to be completed in Sheffield’s Heart of the City 2 development. Prior to this, the site was occupied by a 1960s concrete block, topped by the Grosvenor House Hotel.

But let’s imagine that we can peel back time, to when this would have been wild moorland. The year was 1682 and a small house was built here. For whom, we shall never know, but it was extended over the next hundred years, and marked the edge of Sheffield town. Beyond the house was Sheffield Moor, a barren stretch of land, reputedly dangerous to cross, that stretched from the town boundary until it reached a small hamlet called Little Sheffield.

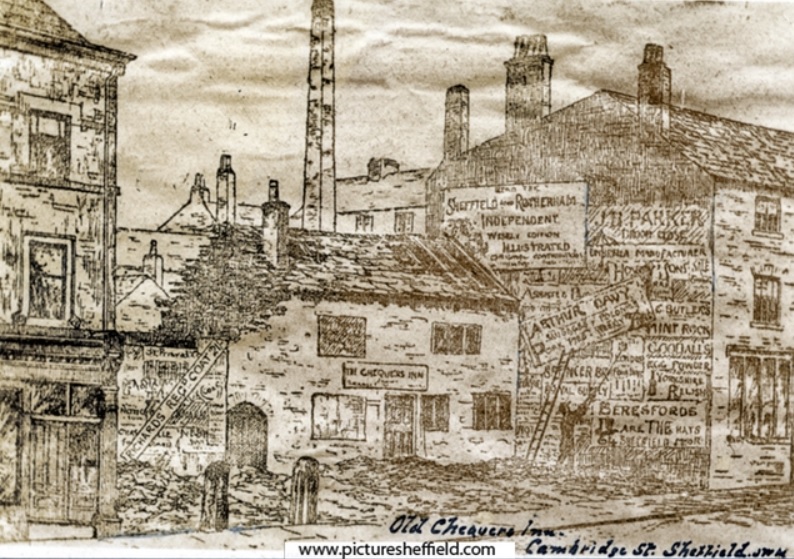

The likelihood is that somebody saw a business opportunity because by the early 1800s the house had been converted into an inn and stood on Coalpit Lane (renamed Cambridge Street in the 1860s).

“It was originally the last house in Sheffield, where the weary traveller, journeying between London and the immediate towns, could refresh themselves in the ‘qualifying flagon’ of home-brewed ale.”

In front of the inn stood two posts that held stocks in which evildoers were fastened and exposed to the jeers of passers-by. It was a frequent sentence inflicted on anyone found tippling during the hours of Divine service on Sundays or playing pitch-and-toss. The victims in the stocks were seated, and their ankles held fast.

Sheffield was well supplied with stocks. At one time, stocks and a pillory stood by the Town Hall which at that time was situated where the entrance to East Parade is now. There were also stocks at Attercliffe, Bridgehouses, and Fulwood.

It was a puzzle as to why there were stocks outside the Chequers Inn, especially as it was so close to the Sheffield stocks. This side of Coalpit Lane was actually outside the town boundary and the start of Ecclesall, and it was likely that the Sheffield constable (to save the rates) handed over a vagabond to the Ecclesall constable, and this was the ideal spot for him to be placed until released by the Ecclesall official and then he would be transferred from one place to another until his birthplace was found, and who would be compelled to keep him.

The Chequers Inn, also briefly known as the Old Cow, was in the Alsop and Barker family generation after generation, when it was purchased by James Padley, whose sons (one was the Borough Accountant) sold the property to Daniel Henry Quigley Coupe.

D.H. Coupe came from Worksop as a young man and had many ‘irons in the fire’, starting out as a labouring carter before buying the business of his employer Mr Milner. He grew the business until he owned 82 horses and carts before branching out into the coal trade at Midland Station. After he sold his coal business, he moved into the brewing industry and was sole partner in D.H. Coupe and Co, of the Albion Brewery, Ecclesall Road. He was the largest cottage property owner in Sheffield and paid more rates than any other man in the town.

By the time he bought the Chequers Inn, Sheffield had rapidly expanded, and it no longer backed onto the countryside. Not only that, but the inn was in a poor state of repair. In 1860, slates and stone slabs had fallen off the roof, followed directly by the roof itself. Chequers Yard, behind the inn, was a coal yard, and contained notorious lodging houses, home to vagrants in a hopeless state of destitution and disease.

D. H. Coupe’s plans for the Chequers Inn was to demolish it and erect a new hotel on its site while retaining its old sign, one of its quarterings being the coat of arms of the old Lord of the Manor. However, he died in 1883 and the executors did not see their way to carry out the project, hence it remained in dilapidated condition.

The area bordering old Sheffield Moor had become known as Moorhead, and when the town started its street improvements programme, the Chequers Inn owed its survival because it stood just above the point where New Pinstone Street cut through Coalpit Lane (Cambridge Street). The demolition of properties around it brought the Chequers into daylight again and a ‘somewhat out-at-elbows appearance’, and the inrush of light had proved so dazzling that the windows were boarded up and accentuated the poor condition of the public house. The uninhabited appearance meant that its days were numbered, and a report from this time stated that one of the old stock stones had fallen. It was a far cry from the days when writers had referred to the smart Chequers Inn with its grass plot facing the street, but in its last days that grassy plot had been used as a skittle alley.

T and J Roberts, milliners, had built a grand new shop at the corner of Cambridge Street and New Pinstone Street in 1882 and they purchased the Chequers Inn to construct a Cambridge Street extension in 1888.

Workmen who demolished the Chequers Inn came upon a stone lintel which bore coloured checks – blue, red, etc. – bright as the day it was painted. The sign had been papered over and above the lintel was the name of ‘Alsop’. Other stones laid bare had the date ‘1682’ carved into them. There is some mystery as to what happened to the old stones that had supported the stocks. Charlesworth Brothers, who built Roberts extension, stated that they had been used intact in the foundations of it, but a letter to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph claimed that a passer-by had bought them with the intention of presenting them to Sheffield for display in one of its parks.

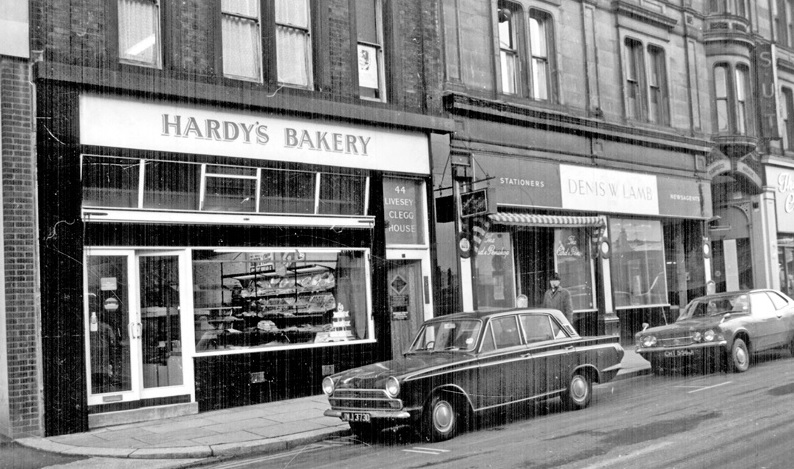

Alas, the Chequers Inn disappeared and was quickly forgotten. T and J Roberts closed its shop in 1937 and the building survived until replaced by the 1960s concrete construction that was in turn demolished as part of the recent Heart of the City redevelopment.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.