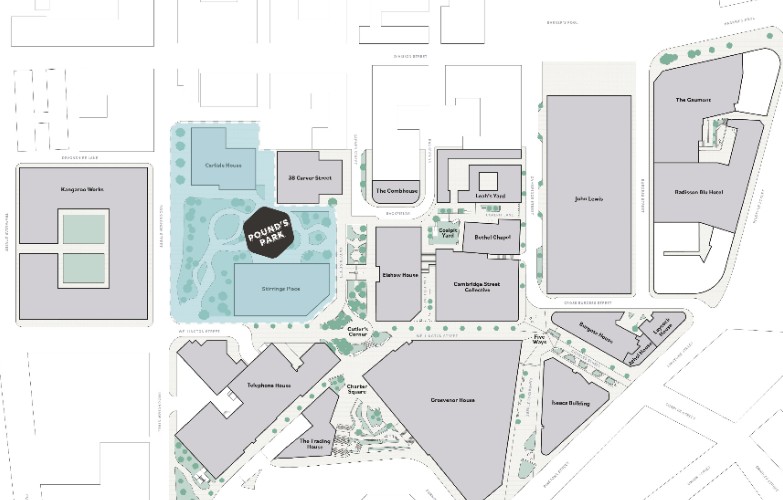

We recently looked at St. Matthew’s Church on Carver Street that was built in 1854-1855. Next door is an equally important building that is known today as The Art House, a trading name of St Matthew’s House, a charity set up in 2011 to support people with mental health issues and allow them to engage with the creative arts.

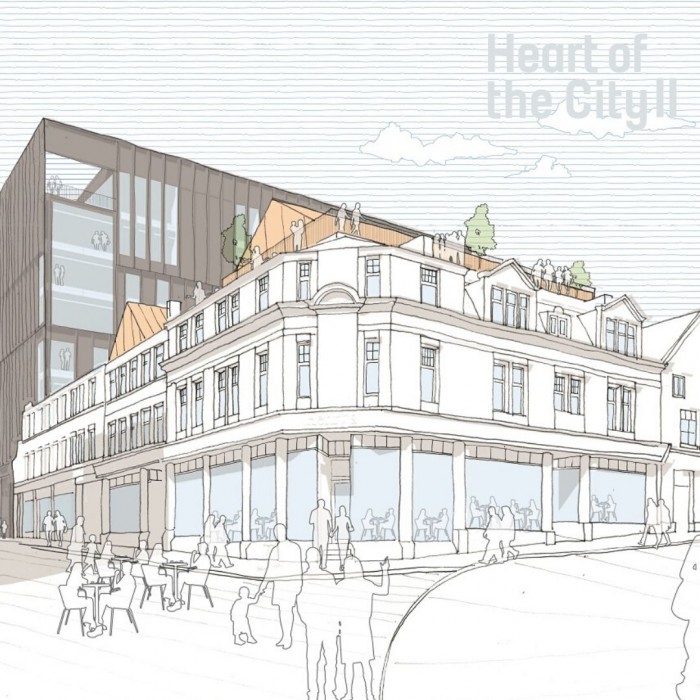

It was originally called Clergy House, built in Tudor Gothic style in 1896 as a home and parish rooms for the Rev. George Campbell Ommanney, vicar of St Matthew’s Church between 1882 and 1936, and two assistant priests.

The old vicarage, as far away as Highfield, was sold in 1884, and for several years the vicar and his clergy lived in seedy rented accommodation at No. 71 Carver Street, close to the church.

“A vicar who is willing to make the sacrifice involved in taking up his abode in such a dingy, insalubrious district at that which contains St. Matthew’s ought at least to live in a comfortable house,” wrote the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent in 1896.

At that time, houses beyond those of the very poorest class were scarce in the central parts of Sheffield. All the large ones had been sacrificed to the demands of commerce.

The parishioners sought to remedy the situation, and Rev. Ommanney was able to secure a freehold site adjoining St. Matthew’s Church at a cost of £900. The site had been a public house – the Stag Inn – allowing the vicar to say, “it was a good thing to shut up a public house and get rid of a licence.”

The amount required to build the new Clergy House was £2000 and the vicar used money from the sale of the old vicarage as well as the interest which had accrued against it. The York Diocesan Church Extension Society subscribed £150, and the Sheffield Church Burgesses gave a similar sum. The vicar contributed £450, and two members of the congregation subscribed £100 each. To make up the balance, the vicar intended to borrow £500 from the trustees of Queen Anne’s Bounty, but further subscriptions flooded in and the crowning gift was a grant of £7000 from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. It allowed the house to be built debt free.

The architect was John Dodsley Webster, and it was built in red brick with stone facings. The basement contained the large parish room, on the ground floor were the drawing room, kitchen, and offices, while the first floor contained sitting room, study, bedroom, and bathroom. Five bedrooms occupied the top floor.

Land at the back, on Backfields, was later bought to add parochial buildings, including a Sunday School.

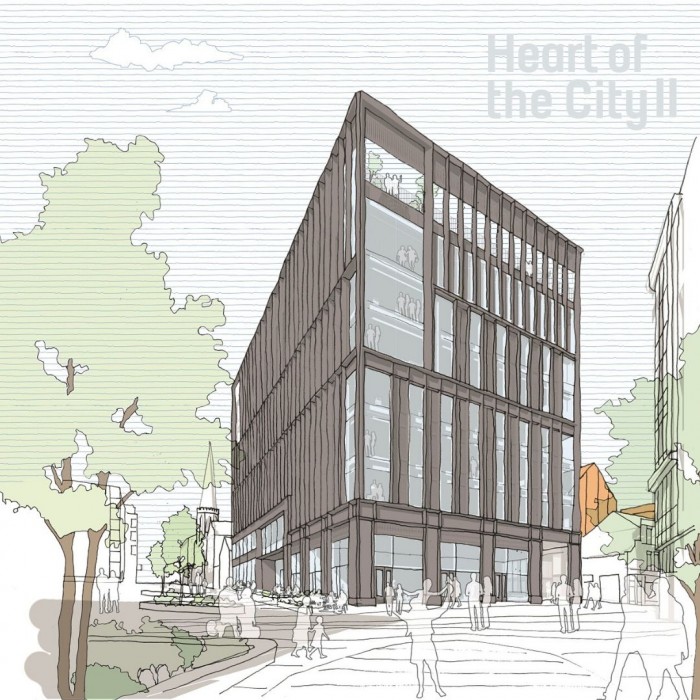

According to the Art House website, time took its toll on the building and the building deteriorated to an extent that a major refurbishment had to be undertaken. A small group of people from the congregation devised a plan to restore St. Matthew’s House to its former glory, and once again play a part in serving the needs of the local community. The Art House Charity was established in 2011 and spent four years raising the £1.5m needed to refurbish the dilapidated building. A modern extension was added to the rear in 2015.

The building is leased to the charity by St. Matthew’s Church at a peppercorn rent.

©2023 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.