When Sugworth Hall, at Bradfield Dale, was on the market last year, it was offered in the region of £1.5million. Not a bad price considering the Grade II listed country house is in beautiful Sheffield countryside, and it has a long history.

According to experts, this was once a farmhouse dating to about 1535, later listed in the will and testament of Robert Hawksworth in the 1560s. Passing down the family it eventually belonged to the Gould family and was extended in the late 19th century.

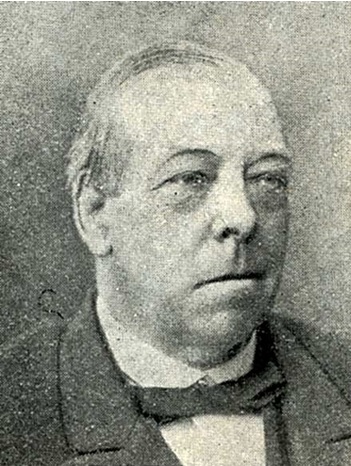

By this time, Sugworth Hall was in the possession of Charles Henry Firth, also of Riverdale House at Ranmoor, son of Thomas Firth, a steel manufacturer, whose company would eventually become Firth Brown. After he died in 1892, the house passed to his widow and eventually put up to let as a substantial family residence or shooting box.

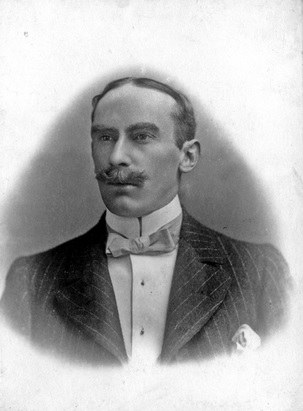

It was subsequently bought by Philip Henry Ashbury of Mushroom Lane, managing director of Philip Ashbury and Sons, Bowling Green Street, silver and electro-platers, who used it as a “delightful summer residence” until his death in 1909.

It was inherited by his son George W. Ashbury, a man who soon made headlines by accusing two of his servants of stealing beds, bedding and towels and was promptly sued for libel, his accusations costing him £15 in damages.

The house was briefly occupied by Alfred Percy Hill, of the firm of J and P Hill, engineers, and later Russian Consul for Sheffield, and by the early 1920s it was owned by Charles Boot (1874-1945), son of Henry Boot, founder of the famous Sheffield construction firm, and notable for creating Pinewood Studios.

It was Charles Boot who made significant alterations and extensions to the house, with a tower and battlements, probably the work of architect Emmanuel Vincent Harris, the man who designed Sheffield City Hall.

The work is said to have taken place around 1930, about the time Vincent Harris was working on Sheffield’s new civic building, but based on the architect’s workload, it seems more likely the alterations were made between 1926-1927.

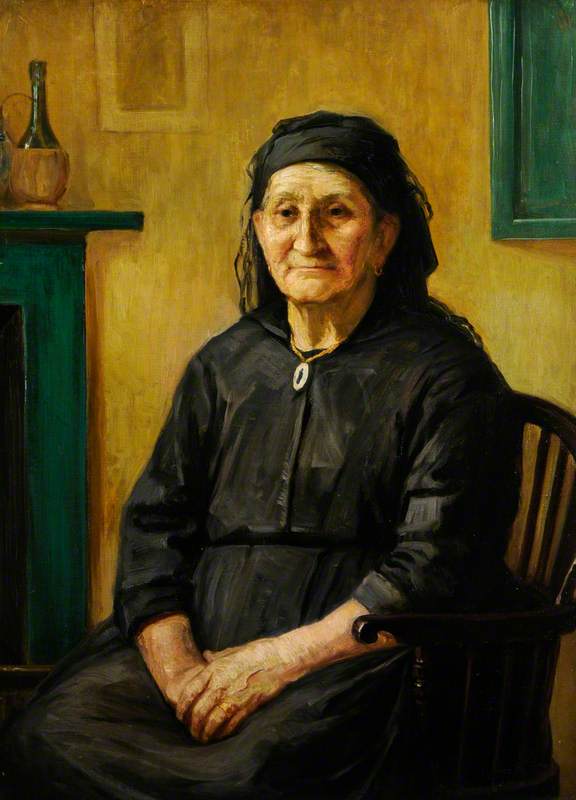

Boot’s wife, the splendidly named Bertha Boot, died at Sugworth Hall after a long illness in 1926, giving rise to speculation that an isolated tower, Boot’s Folly, built in 1927, about 330 yards to the north, was constructed so that he could see the graveyard at High Bradfield where she was buried.

Another story suggests that Boot’s Folly was built to provide work for Sugworth Hall’s workmen during the Depression, but more likely it was built as an observation tower for Boot and his guests to view surrounding countryside.

Whatever the reason, Charles Boot remarried five months later, to Kate Hebb, at St Peter’s Church in London.

Charles Boot bought Thornbridge Hall, near Bakewell, in 1930, declaring that this would be his main residence, and that Sugworth Hall would be maintained as a shooting box instead.

By 1934, Boot had sold Sugworth Hall to Brevet-Colonel William Tozer, of the Hallamshire Battalion of the York and Lancaster Regiment, the grandson of Edward Tozer, one of the founders of Steel, Peech and Tozer, steel manufacturers.

Having lived for fifteen years at Grange Cliff, Ecclesall, Tozer became Master Cutler in 1936, the ceremony highlighted by Anthony Eden, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, and later Prime Minister, coming to stay at Sugworth Hall.

The Tozer’s left Sheffield for Buckinghamshire in 1939 and since then Sugworth Hall has survived quietly in Bradfield Dale.

Boot’s Folly has fared less well. The 45 feet high tower, 20 feet square, once had a furnished wooden panelled room at the top, connected by a spiral staircase, but has sadly become ruinous over time. (The staircase allegedly removed after a cow ascended the steps and became stuck).