We forget about Attercliffe, and so it is inevitable that we forget its lost buildings.

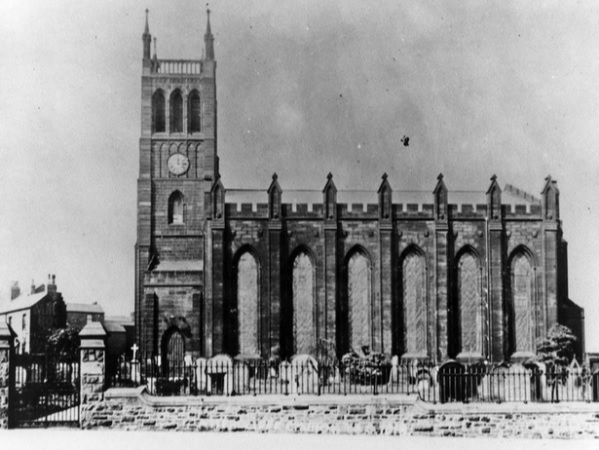

One example is Attercliffe Parish Church, also known as Christ Church Attercliffe, once a grand place of worship, badly damaged in the Sheffield Blitz of 1940 and later demolished.

And we might be forgiven for not knowing where it stood, but its site is plain to see.

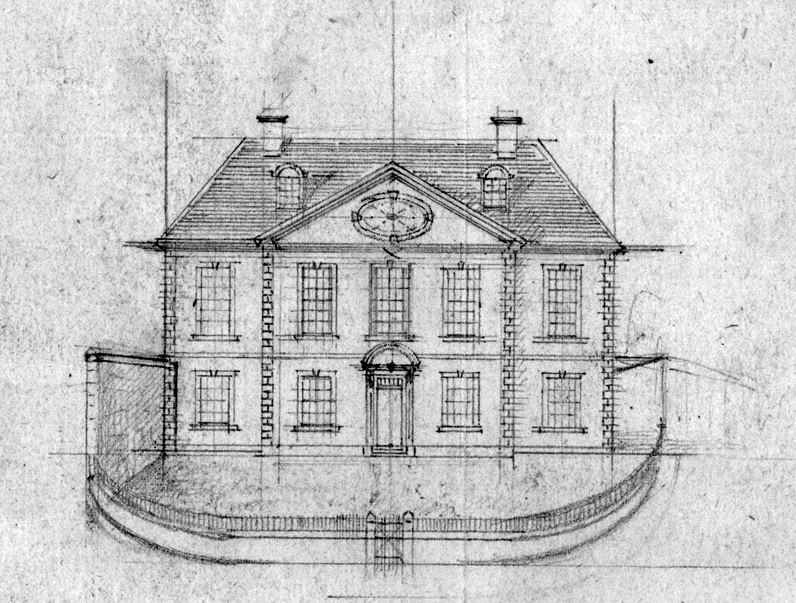

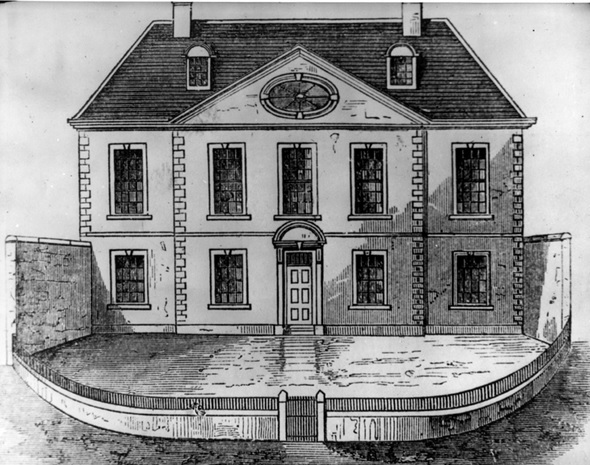

We can turn to Pawson and Brailsford’s Illustrated Guide to Sheffield (1868) for details: –

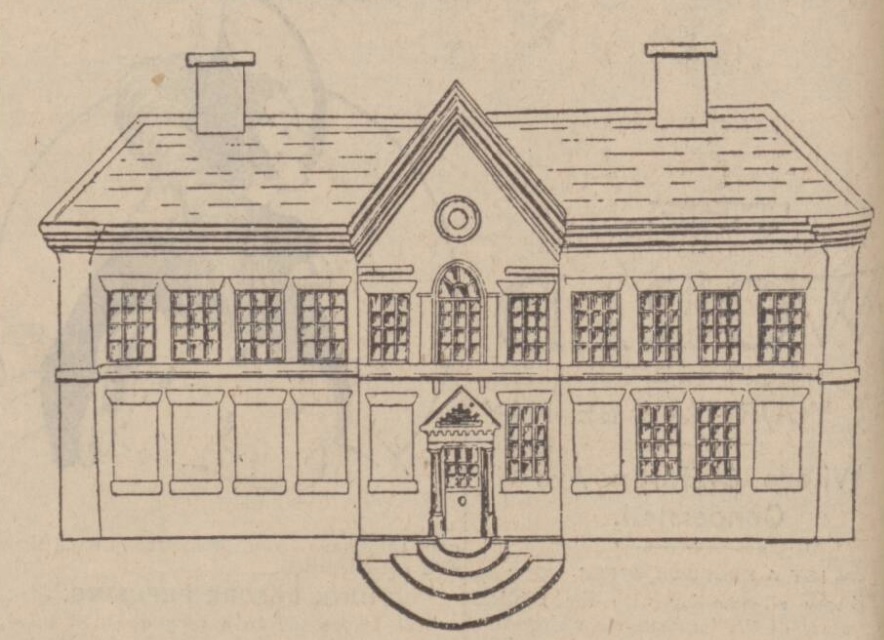

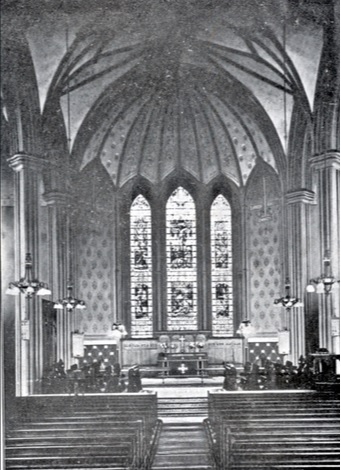

“There is a handsome church at Attercliffe, which is about two miles from the centre of town, on the Doncaster Road. Formerly Attercliffe was a detached village, but now it is practically a busy manufacturing suburb of Sheffield. It was opened in 1826, having been built by means of a Parliamentary grant, at the cost of £14,000. It is a Gothic building, with lancet windows and a handsome groined roof. It will accommodate from 1,100 to 1,200 persons.”

The old chapel-of-ease of the Township of Attercliffe-cum-Darnall, dating from the 17th century, had been replaced by the new church.

Attercliffe, at that time, was a comparatively small place, and largely consisted of lanes and fields, and the new church was one of four churches built in Sheffield out of what was known as the ‘Million Fund.’

The nucleus of the building fund consisted of a grant from an indemnity paid to England by Austria after the Battle of Waterloo.

The first stone was laid by the 12th Duke of Norfolk assisted by the 4th Earl Fitzwilliam in October 1822 and took four years to build. It was consecrated by the Archbishop Vernon Harcourt of York in 1826.

Early directories referred to the church as standing near the bold cliff which overhangs the Don.

“Time was when Attercliffe was a place of sylvan beauty and picturesque repose, of pleasant pastures and stately houses on the banks of a River Don whose waters were clear and transparent.”

“In the church, there are galleries on the sides and at the west end; which, with the pews in the body of the church, contain two thousand sittings. Some of the windows of the church are ornamented with painted glass, containing the arms of Fitzwilliam and Surrey, Gell, Milner, Staniforth, and Blackburn.”

The churchyard closed for burials in 1856 and a cemetery leading down to the Don was opened in 1859.

In 1876, the church was closed for cleaning and redecoration.

“Below the windows the walls are tinted puce, but above they are straw-coloured, with ornamental work above the windows. The groins are picked out in stone and the roof is coloured buff. White is the groundwork of the chancel roof, but other tints are introduced.”

The church didn’t forget the men who served in World War One, and at a cost of £300 a memorial was erected in the form of oak reredos and panelling together with remembrance panels framed in oak, bearing the names of all those who answered the call of their country.

By the time of its centenary in 1926, the parish embraced around 33,000 souls, but it was a different place.

“The mere mention of Attercliffe to those who are closely acquainted with it is scarcely calculated to send them into ecstasies of delight, for the very sound reason that Attercliffe has precious little that appeals to the aesthetic sense. Attercliffe and throbbing, thriving industry are – in normal times – synonymous terms, and when the clang and clatter, the smoke and grime of heavy trades fill the air, Attercliffe, from the casual visitor’s point of view, is a place to get away from rather than to remain at.

“Looking back upon a picture of a rural landscape, with its common (now filled with shops), its thatched cottages, and its sheep grazing on the riverbanks, the individual might well exclaim: ‘All this has changed.’”

The church was in debt for years, especially after the installation of electricity, and following the departure of Rev. A. Robinson in 1930, the church revealed that its finances were “vague and confused,” and that he had left a debt of £550-£600.

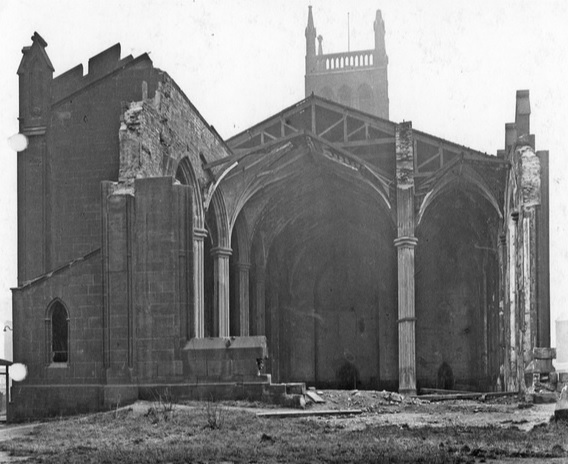

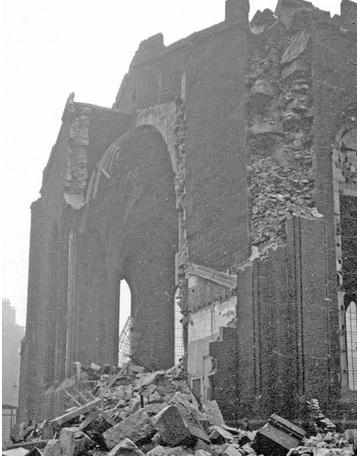

Unfortunately, the church was closed after bomb damage in 1940. Most of its contents were destroyed and Sheffield lost one of its finest churches.

The organ from the blitzed church was rebuilt and taken to St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church on Hanover Street.

The adjacent church hall became the parish church until 1950, and then functioned as a chapel in the parish of Attercliffe-cum-Carbrook until it was closed in April 1981. The new church of St Alban (Darnall) is now the parish church of Attercliffe.

In 1953, the site of the old church and its graveyard was turned into a garden, an area of pleasant green turf bordered by paths. It was opened by the Lord Mayor, Coun. Oliver S. Holmes, who said, “it was inspiration to the whole city that good will make beauty rise from the rubble of war.”

The church site and the garden of remembrance can be seen on Attercliffe Road, opposite the Don Valley Hotel. Access is available into old Attercliffe Cemetery behind and the Five Weirs Walk.

NOTE

A rare book, ‘The Church in Attercliffe,’ by Rev. Arthur Robinson, was published to celebrate the church’s centenary in 1926.

©2022 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.