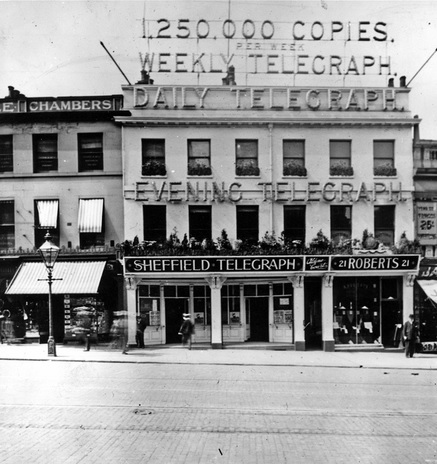

Photograph by Google

The next time you are able walk into McDonalds or HMV, on High Street, be aware that you are walking into history. Before you go inside, take a moment and look above, and you will find that these popular ground floor premises are part of an elaborate building.

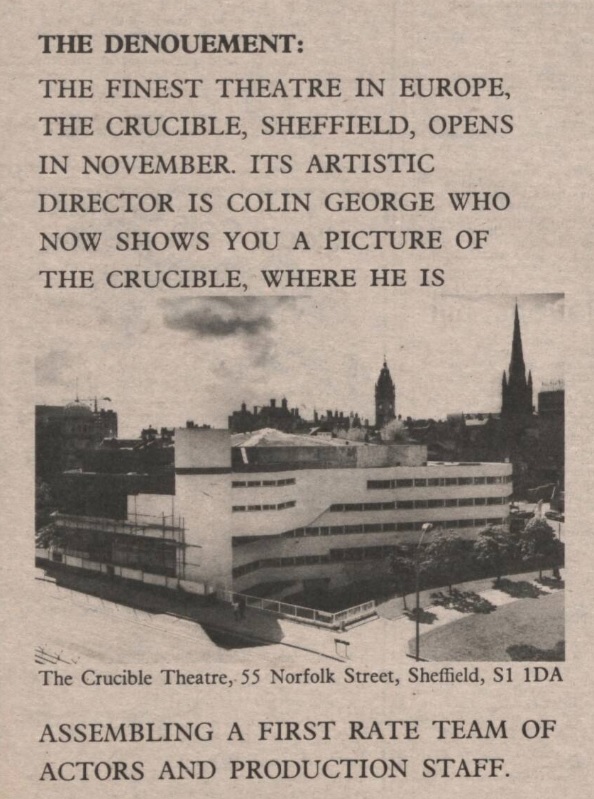

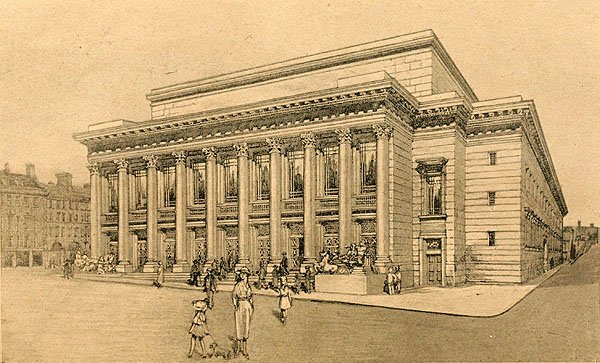

This is the Foster’s Building, built in French domestic Gothic style by Sheffield architects Flockton and Gibbs in 1896.

The origin of the Foster’s Building goes back to the Anglo-French Wars of the sixteenth century, and the entrepreneurship of William Foster, draper, tailor and outfitter, who opened a shop on High Street in 1769.

At the time that William Foster opened his business, High Street was a narrow thoroughfare, described by some as resembling a village street.

When peace was concluded with France, the British Government advertised for sale a vast stock of old uniforms and equipment, which had been given up by troops on disbandment.

William Foster took a coach to London and bought up large quantities of soldiers’ jackets and belts. These were brought to Sheffield and stacked in large crates and baskets outside his shop.

It was said that there was hardly a grinder or cabman in Sheffield who did not buy one of the jackets, not particularly concerned about appearance, but appreciating something cheap.

Being extremely durable they were suited to both trades, and a credible record suggests that the old workshops looked as though a regiment of soldiers was at work, for every grinding wheel had a red-jacketed attendant.

The army belts were of excellent leather, so the record runs, and were largely used by craftsmen for buffing and similar purposes.

Foster was afflicted with an obscure disease, the chief symptom of which was that he frequently fell asleep.

“Mr Foster fell asleep while seated on the hampers of soldiers’ clothes. These used to stand on the edge of the pavement, and there Mr Foster sold the contents, so long as he could keep awake,” said an old humourist.

According to George Leighton in Reminiscences of Old Sheffield (1876) there were other amusing consequences of Foster’s illness.

“I went once to him, as a boy, to be measured for a jacket. Standing behind him, he made me hold my arm horizontally, with the elbow bent, and I thought he seemed a very long time in measuring it. A person on the other side of the street, at York Street corner, was watching the operation, and, seeing him laughing, I looked round, and found that the old man had fallen fast asleep.”

Photograph by Picture Sheffield

Photograph by Picture Sheffield

William Foster made a huge sum of money from the transaction and left his family very wealthy.

He was succeeded by his son, also William, who subsequently went into partnership with his own son, George Harvey Foster, in 1860, and renamed the business William Foster and Son, operating at 12-14 High Street.

It soon became necessary to enlarge the premises, and for this purpose, they acquired an adjoining public house, the Spread Eagle, and incorporated it into the original building.

Photograph by Stephen Richard/Geograph

And so, we come to the building that we see today.

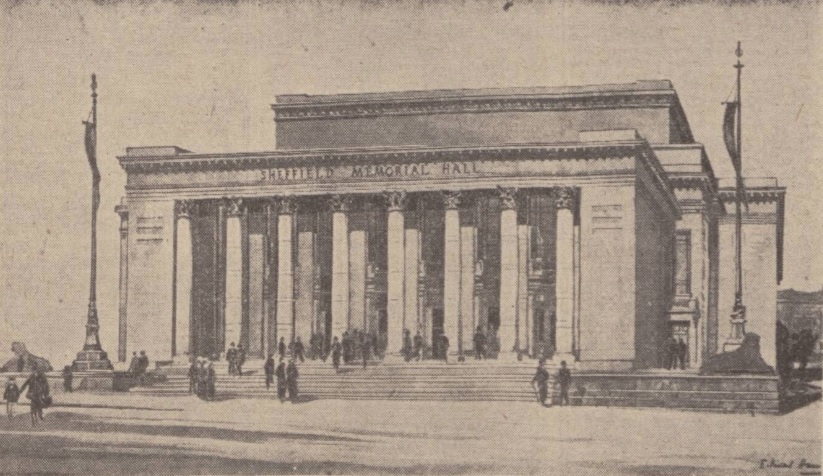

When Sheffield grew in prosperity during the late 1800s, the council considered various schemes to improve the condition of its streets. The High Street improvement scheme finally concluded in 1895, resulting in one of the city’s biggest redevelopment projects, and doubling the width of the street.

However, to allow the road widening it meant the demolition of the old properties on the south side of High Street, including buildings owned by William Foster and Son.

George Harvey Foster sold 400 yards of freehold land in High Street for £34,000 in 1893. He took £24,000 in cash for the site of the tailor’s shop, and £10,000 for adjoining land that he owned, and needed by Sheffield Corporation.

Foster died in 1894, his will confirming that he had sold the frontage of the High Street property to Sheffield Corporation for road widening, and empowering his trustees to rebuild and rearrange replacement premises.

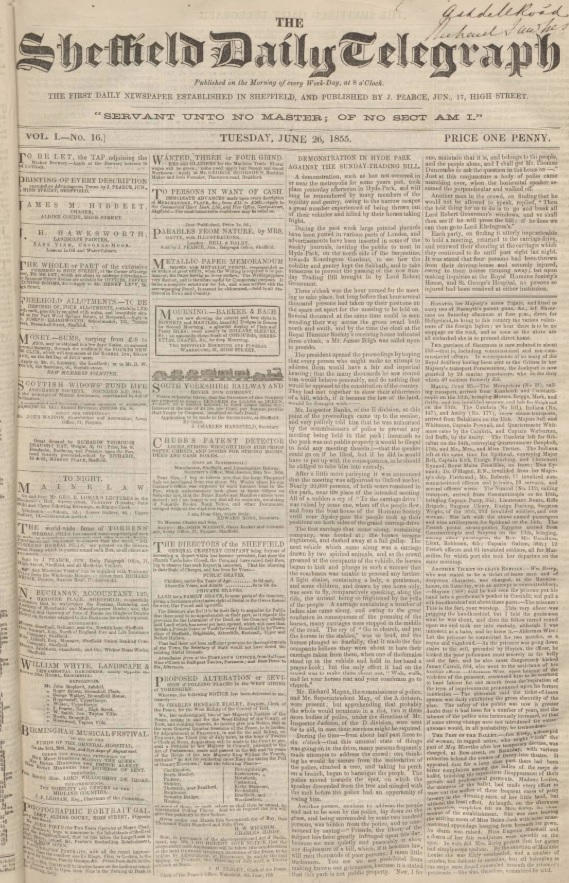

Photograph by The British Newspaper Archive

In 1895, the first plans for the new building were issued by the architects, Flockton and Gibbs, and convinced the public that this was an “ornament to the widened street.”

The chief architect for the building was Edward Mitchel Gibbs with construction work starting in 1895, undertaken by George Longden and Son, with ironwork supplied by Carter Brothers (surprisingly based in Rochdale).

The building stood on a new street line, set back about forty feet, that allowed existing shops to continue trading during construction, and be demolished afterwards.

When the Foster’s Building was completed in late 1896, it accommodated previous tenants from the old site , Foster and Son being the principal tenant, with other shops for J. Harrison, hosier, C. Tinker, boot and shoe manufacturer, E. Brown, goldsmith and Mr W. Lewis, tobacconist.

Foster and Son had two entrances, with four large windows. Their frontage was 86 feet long and 100 feet in depth and came with a large back yard, and within, contained all three of their departments – ready-made clothes, children’s and bespoke tailoring.

A balcony extended across the top of the building, while Gibbs set back the main wall of the frontage about two feet, so that the supports would not interfere with ground floor window space, and was described as being a “huge showcase”.

The Foster’s Building, on a slightly sloping site, was built in a curved line, leading towards the bottom of Fargate.

The front of the showrooms, above the shops, was ornamented with light wooden tracery, and the upper parts of the building (four floors) was of Huddersfield sandstone, richly moulded, and with a steep-pitched slate roof. It was relieved by oriel windows, ornamental gables and turrets, and dormer windows.

The whole of the upper floors was utilised as rented offices, varying in size, approached by a staircase, ten feet wide, leading from High Street, and by a passenger elevator (see note at end). Each office was fitted with “electric wiring, gas tubing and all modern conveniences.”

The corridors on each floor were eight feet wide, with mosaic-tiled floors and tiled walls up to the height of the door heads, These were well lit by windows placed at the end of each corridor, and also borrowed light from the offices.

The office entrance was marked by a lofty arch, with oriel windows over it, surmounted by a gable, with turrets, and crowned with an ornamental tower, which was to have been the water tank for the elevator, had not “technology” quickly intervened.

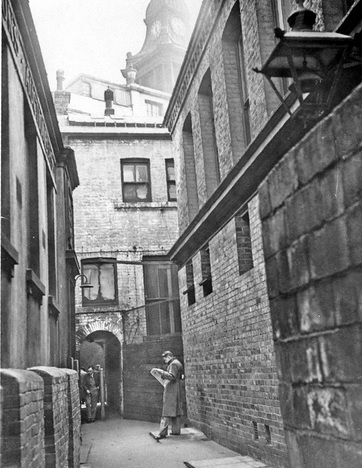

Photograph by Picture Sheffield

Foster and Son remained in the High Street until 1931, by which time they had been here for over 160 years. It was the oldest tailoring firm in the city, with other premises at Waingate and Castle Hill, and had been run by the widow of William Joseph Foster, great-grandson of its founder, since 1905.

Foster and Son consolidated trade at its other shops, and while war had been instrumental in its initial success, it effectively led to its demise after the Waingate branch was destroyed during the Sheffield Blitz.

The Foster’s Building eventually succumbed to other retailers at street level and, for a time, was known as Norwich Union Buildings. It was refurbished during the late twentieth century, presumably with much period detail lost, and before it was Grade II-listed by English Heritage (now Historic England) in 1989.

Photograph by Picture Sheffield

Photograph by Stephen Richard/Geograph

NOTE: –

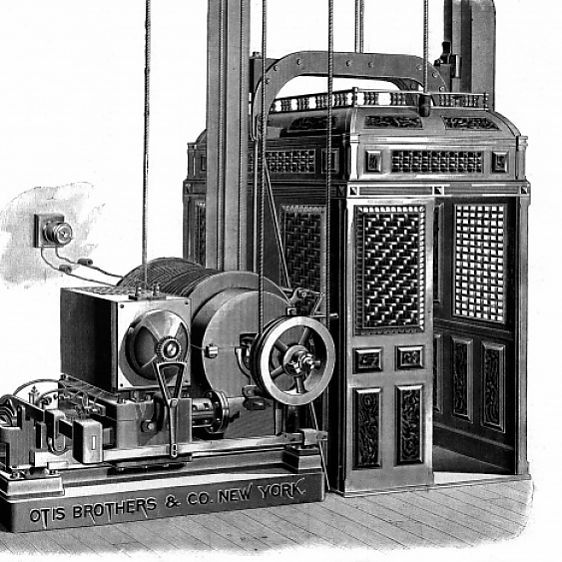

The Foster’s Building had the first American Elevator in Sheffield, built by the Otis Elevator Company, founded in Yonkers, New York in 1853 by Elisha Otis.

In 1890, Otis had entered the British market under the name of the American Elevator Company. Between 1870 and 1900, there had been a transition between hydraulic lifts to electric-powered elevators.

The Otis company advertised its new generation of elevators with the consideration that such an installation was no longer a complicated matter, and well-suited to places which could not have had one before.

The Foster’s Building had intended to have a hydraulic lift and Gibbs’ design included a small water tower on the roof for its elevator. After it was decided to install an electric-powered lift the tower remained, but instead used as a motor room for the American Elevator.

In 1897, a newspaper advertisement for potential occupiers of its offices described the lift as being able to “accomplish the journey from ground floor to fourth floor in THREE seconds.” Unlikely, even today.

Photograph by Getty Images