For hundreds of years there have been rumours of secret tunnels that existed between Sheffield Castle, going towards the Parish Church (now Sheffield Cathedral), and heading out to Manor Lodge and the Old Queen’s Head at Pond Hill.

After an underground tunnel was found underneath Angel Street in the 1890s, dismissed as an old sewer, interest in the stories waned.

However, excitement resurfaced in 1920, when discoveries were made at Skye Edge as a result of a coal strike.

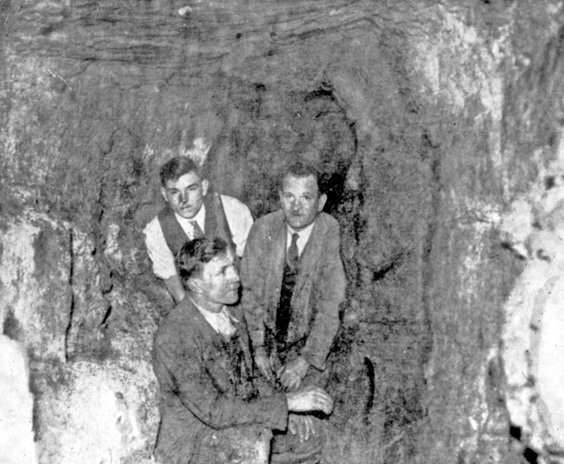

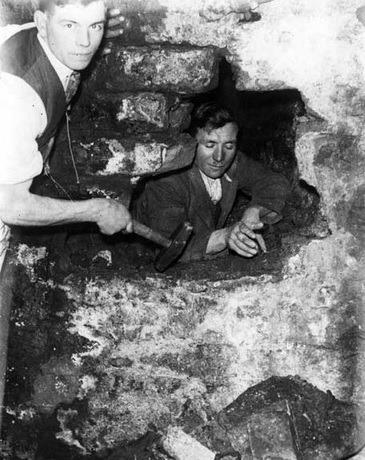

In order to keep engines running in a nearby brickworks, several men were digging coal from an outcrop on Sky Edge quarry, when they unearthed what appeared to be a subterranean passage cut out of the solid ironstone.

Sky Edge was amid many historical associations – the old Manor Lodge to which Mary Queen of Scots was held captive – was less than a mile away.

It was possible to penetrate for about 100 yards with a naked light, but further on the tunnel appeared to show signs of caving in, and the presence of foul gases made it unwise for the men to carry on.

The main passage had an arched roof, 6ft high, and the floor was on a seam of coal, 3ft thick.

In the light of similar discoveries made at the time, in River Lane, near Pond Street, and at High Street, the discovery raised the possibility that the tunnel at Sky Edge was part of a subterranean passageway which at one time connected Sheffield Castle at Waingate (where the unfortunate Queen was also imprisoned).

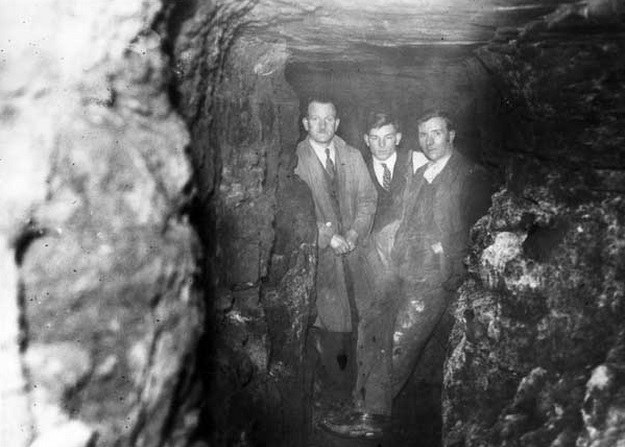

Four years later, Sheffield Corporation workmen laying sewers near Manor Lodge unearthed another tunnel, at a depth of nearly 10ft deep, although it ended in a heap of dirt and stones.

The tunnel ran across the road towards Manor Woods. Explorations revealed that in the direction of the Castle the passage was only about ten yards long, apparently demolished at an earlier stage. But in the opposite direction it was possible to walk about 50 yards.

At the time, it was thought that it had some connection with a tunnel found at Handsworth two years previous.

In some places the roof of the tunnel had shifted slightly, thought to have been caused by ploughing operations above, where coping stones had previously been unearthed.

A reporter from the Sheffield Daily Telegraph was invited into the tunnel.

“All sounds from the outside world are cut off, and the thought that people long since dead had trodden the same path was decidedly eerie. The floor, walls, and roof are all made of stone, some of the blocks on the floor being of quite considerable size and thickness.”

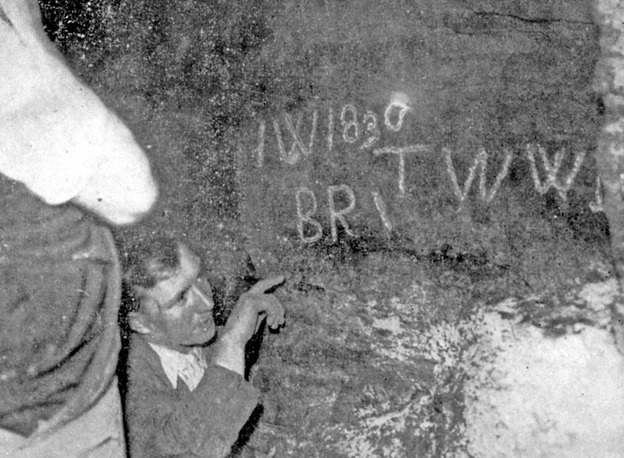

An old man at the time, told the same newspaper that he knew of the passage, as it had been opened for the Duke of Norfolk about fifty years previous.

“The tunnel was opened out in the field, and one day, I, in the company of other lads, went on a tour of exploration. We took our lamps with us and were able to walk for quite a considerable distance in the direction of the castle. At last, however, our progress was arrested by a heap of stones and earth and we were compelled to return. I remember the incident well enough because we all got a “belting” when we returned.”

Another claimed that he knew where the tunnel came out of Manor Lodge.

“One had to go down a number of steps into a cellar and from there it was possible to walk some distance along a corridor until a heap of rubbish was encountered. The cellar was within a few yards of the road, being near the large ruined tower,”

The secret tunnel to Sheffield Castle is said to have been through a small opening which was situated in a wall dividing the Lodge from the grounds of the Turret House. This had been boarded up at the time, but rusty staples suggested the fact that years before a strong door was fitted to the passage.

The secret way possibly served two ends. It could either have been used as a means of escape when the Lodge was surrounded, or to assist in the hunting of deer which once abounded in the vicinity.

The legend that Manor Lodge was connected by a subterranean passage to the Castle, the two homes of the Shrewsbury’s, was an old one. But one that suggested that Manor Lodge was connected to the Old Queen’s Head Hotel in Pond Hill had only surfaced later.

There was evidence from a few years before in Thomas Winder’s British Association Handbook and Guide to Sheffield (1910):

“We know that there was a chapel in the Manor House, from the account of the funeral of the 5th Earl, but its position is unknown. The corpse was secretly brought from the said Manor to the Castle.”

Some years before, an underground passage had been discovered, about 4ft high, during drainage excavations under Castle Hill, a passage that was never explored further.

According to that writer, the secret passage from the Manor might have ended near Castle Hill, and not the Old Queen’s Head. Furthermore, the height of the Castle Hill passage corresponded with that of the Manor – about 4ft – whilst the supposed entrance at the Old Queen’s Head was said to be half as high again.

Drainage excavations, which led to the discovery of traces of a passage were referred to in “Rambles Round Sheffield (1915). The writer mentions the Lodge-end of the supposed passage.

“The old lady (custodian at Manor Lodge) will point to the entrance to the subterranean passage which is said to have connected the Lodge with the Castle. During drainage excavations at the castle years ago, traces of a passage were found, but the workmen smashed them in before attention was directed to them. Perhaps some day efforts will be made to trace the passage.”

It was possible that there were two passages, one going from the Castle to the Manor, and the other from the Castle to the gabled structure in Pond Hill (now the Old Queen’s Head), but supposed to have been the laundry of the Castle.

With regards the Old Queen’s Head, a reporter from the Sheffield Daily Telegraph visited in March 1925 and spoke with the landlord, Mr Ellis.

“Yes, there is an old tunnel here,” he said, “which is supposed to go to the Manor Castle, but it is all stoned up, although the entrance can plainly be seen.”

Proceeding into one of the cellars, the reporter was shown the entrance which faced in the direction of Midland Railway Station and was about six feet high. It was impossible to go in, as within two feet of the wall a strong stone barricade had been erected.

“I feel quite sure that this goes to the Manor,” said Mr Ellis, “as since the work commenced up there (Manor Lodge), we have been ‘swarmed’ with rats, and, possibly, they have been driven down here.”

And finally, there was the story of a worker at Steer and Webster, cutlery manufacturers, on Castle Hill, who told his fellows in the late 1800s about the works yard where a shaft or dry well was being used to deposit rubbish, and at some distance down the shaft, on the Manor side, there was an opening, apparently a doorway, which he declared was the entrance to the secret passage to the Manor.