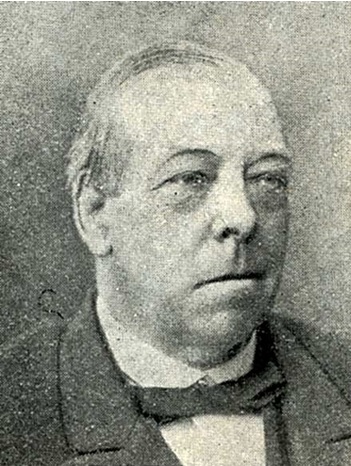

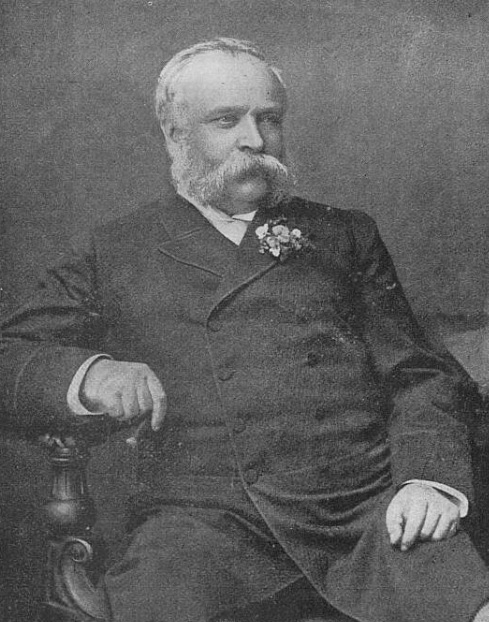

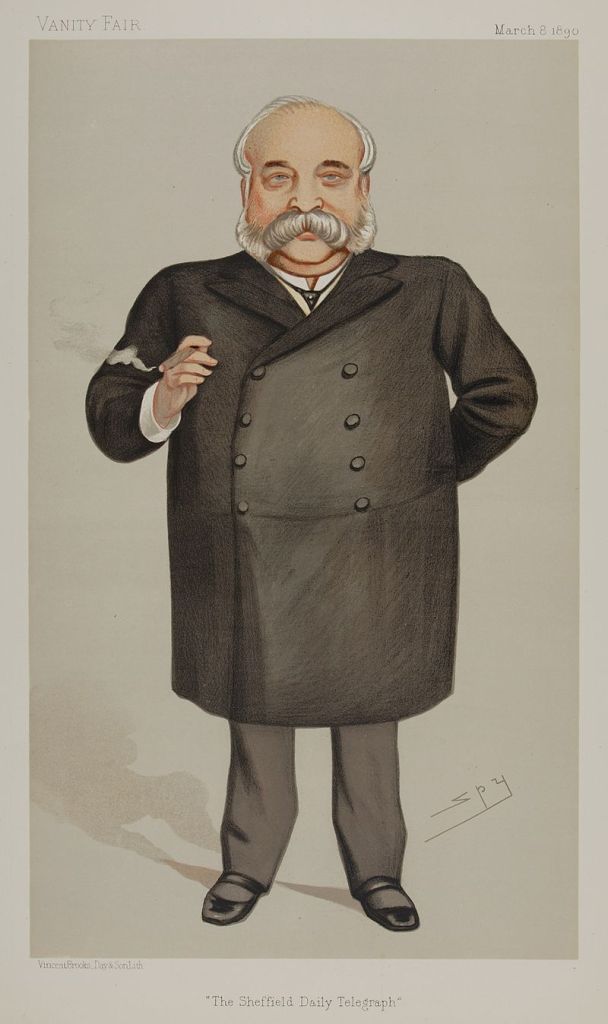

In 1894, The Sketch magazine said that when the romance of journalism was written a very large chapter would have to be devoted to Sir William Christopher Leng, editor and proprietor of the Sheffield Daily Telegraph. “Although there are probably thousands who have never heard his name.”

William Leng was born in Hull in 1825 and started out as a wholesale chemist. He contributed anonymously to local newspapers in Hull – overloading on steamers, the growth of ultramodernism among British Catholics, and parodies in prose and verse on leading writers of the day. He also wrote for the Hull Free Press, featuring sketches of local celebrities, portraying their virtues, foibles, failings, and distinguishing features.

His brother, John (later Sir John Leng, proprietor of the Dundee Advertiser) entered journalism and persuaded William to join his newspaper as leader writer and reviewer.

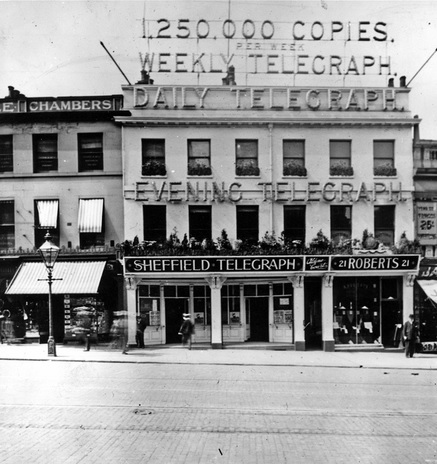

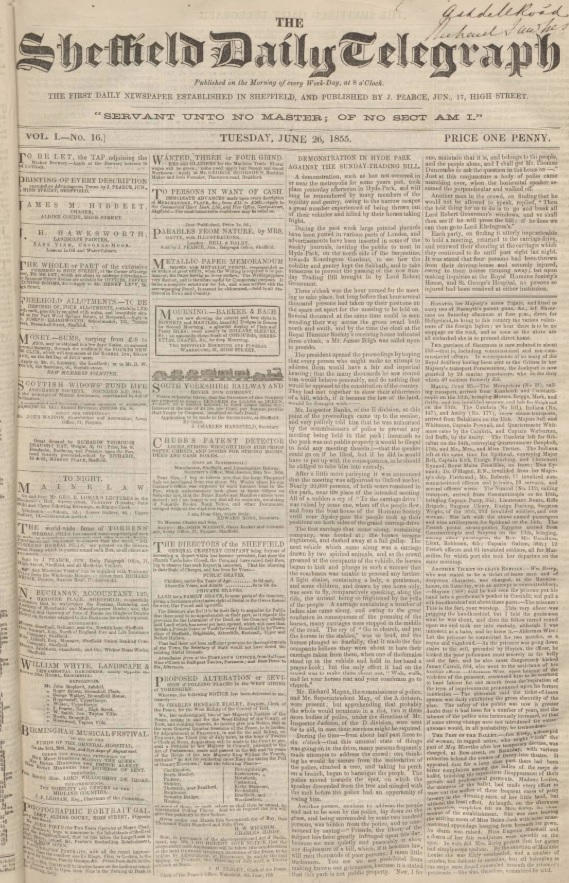

In 1864, aged 39, William entered partnership with Frederick Clifford and purchased the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, the first provincial daily newspaper, becoming its editor and changing its fortunes.

“He brought with him to Sheffield all the Imperialistic traditions of his father, all the anti-slavery feeling inherited from his mother, all his own independence of thought, all his old determinations to make his writings reflect his own beliefs, all that manly courage which led him to defy consequences if only he were faithful to the truth as it seemed to him.”

During his time as editor, he waged war on radicalism, slum housing, American Confederate sympathisers, on the tyranny of trade unionism, and supported Turkey in their conflict with Russia. His association with Samuel Plimsoll was able to revolutionise safety for sailors and prevent overloading on ships.

When he came to Sheffield, Conservatism was at its lowest ebb, but by his writings, he managed to change working class views and by the end of his tenure they held four out of five seats on the council.

At the time, Sheffield was the centre of British trade union revolt, the stronghold of William Broadhead, secretary of the Sawgrinders’ Union, and instigator of murderous trade outrages which paralysed British commerce. If a manufacturer quarrelled with his workmen, Broadhead issued an instruction, and men went forth to destroy his machinery and burn down his factory.

William Leng took up against Broadhead, who sneered at him, having already killed one Sheffield newspaper and confident he could annihilate another. However, Broadhead was unprepared for the broadside that the Sheffield Telegraph hurled at him.

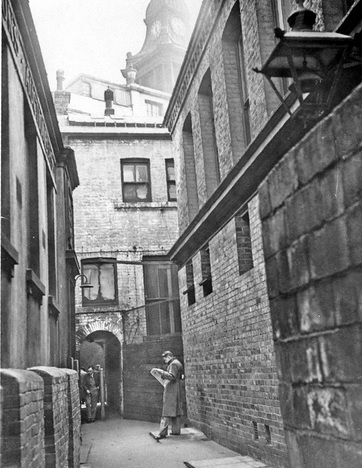

Every day William tossed his journalistic javelins into Broadhead’s camp, and every day was threatened for his boldness. He wrote his leaders with a pistol by his side and walked through the streets at night with his finger on the trigger of a revolver. For weeks he carried his life in his hands.

The ruthless arbiters of Labour had resolved to crush Broadhead, and when a Royal Commission was obtained William had to sit in open court between two policemen for fear that he should be assaulted.

The result of the Commission was a triumph for William, the manufacturers who had suffered at the hands of Broadhead subscribed 600 guineas and presented them to him, and a grateful Government rewarded him for his services by the honour of a knighthood, recommended by Lord Salisbury, in 1887.

William continued writing for the Telegraph until his death in 1902 and was buried at Ecclesall Church.

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph eventually became the Morning Telegraph, surviving as the weekly Sheffield Telegraph, and established what we now know as the Sheffield Star.