He might not have been from Sheffield, but actor Keith Barron owed his success to the city. He was born in Mexborough in 1934, and left its Technical College with ambitions to be an actor, spending eight years with the Mexborough Theatre Guild.

“I had always been interested in the theatre, but my father had a wholesale provisions business and wanted me to take it over. I found it very difficult, so I used to take off and read film magazines. We had a terrible row, he sold the business, and I went into rep at the Sheffield Playhouse in 1956. I had to start at the bottom, making tea for a pound a week for nine months. It’s valuable experience, it makes you really sure that you want to do it.”

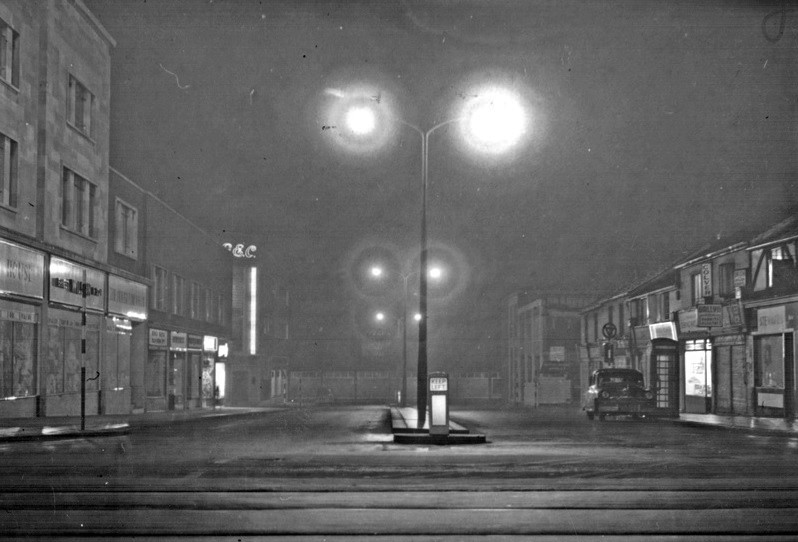

The Sheffield Repertory Company was on Townhead Street and Keith lived on Kenwood Road.

“Visitors to Sheffield Playhouse will be pleased to see Keith Barron making his professional debut in Sheffield Repertory Company’s production of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House. He has the small part of a porter. Although he has only two lines to say and his appearance does not last more than 30 seconds what little he had to do, he does well.”

His first sizeable role was as the spy in Peter Ustinov’s Romanoff and Juliet, and starred in dozens of productions over the next few years, including amongst many, The Winter’s Tale, Frost at Midnight, Graham Greene’s The Potting Shed, A Touch of the Sun, Toast and Marmalade and a Boiled Egg, An Inspector Calls, Blithe Spirit, and as the Rev. Guy Saunders in another Ustinov classic, The Banbury Nose.

In 1959, 25-year-old Keith was described by a newspaper “as a modest, aspiring young man, and standing on the brink of success.”

“There is perhaps, no more impressive moment in a theatre when an audience is moved to spontaneous applause by the sheer power of a player’s acting. This is happening every night at Sheffield Playhouse with Keith Barron in The Ring of Truth,” said The Stage in 1960.

Keith was also amongst Sheffield Playhouse actors chosen to record An Inspector Calls for BBC radio for its Saturday Night Theatre slot.

His departure from Sheffield Playhouse in 1961 was regarded as a serious loss. “A sound young actor with a compelling sense of rhetoric: he has held many audiences enthralled by his command of rapid dialogue accompanied by quick stage movements. He is definitely a live theatre actor, but like too many he is going into television.”

Keith never gave up on the stage, joined the Bristol Vic, and didn’t want to go to London but television was the future.

He appeared as Detective Sergeant John Swift in The Odd Man (1962-65) and the policing spin-off It’s Dark Outside. His first sitcom success was in The Further Adventures of Lucky Jim (1967) and later in No Strings (1974). He deftly switched from comedy to drama, from the title character in Vote, Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton (1965) and as David, in Duty Free (1984-86) about two couples on a package holiday in Marbella and attracted seventeen million viewers.

His other TV roles were prolific, and included Room at the Bottom, Haggard, Prince Regent, The Good Guys, Telford’s Change, Stay with Me till Morning, Take Me Home, Doctor Who, Coronation Street, DCI Banks, All Night Long, Where the Heart Is, Kay Mellor’s The Chase, and Dead Man Weds. And he was in Countdown’s Dictionary Corner on numerous occasions.

Keith died in November 2017, survived by his wife, Mary Pickard, a former stage designer, whom he met in Sheffield and married in 1959, and a son, Jamie, also an actor.

© 2021 David Poole. All Rights Reserved