The recent post about WH Smith created a lot of interest, and this got me thinking about another Sheffield building associated with the company. Not as a shop, but as wholesale premises.

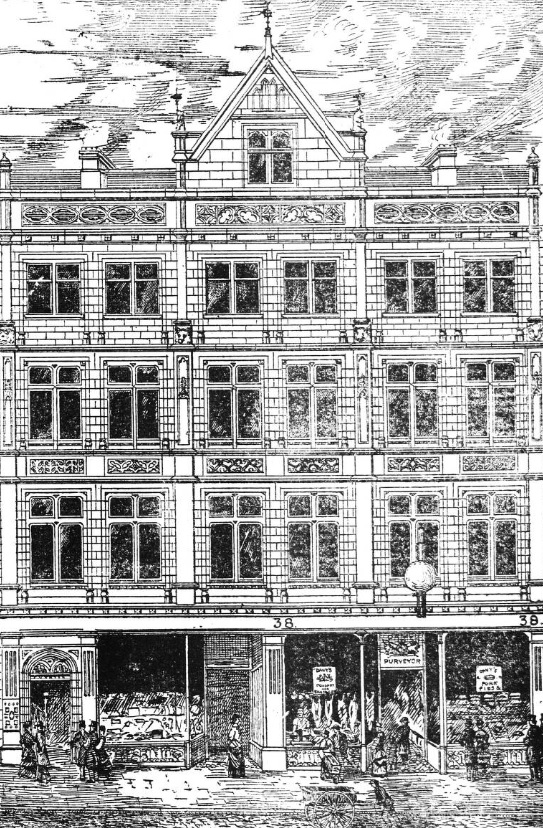

I’m referring to Hambleden House, at Exchange Place, often ignored by historians, that was built 102 years ago, and a fine example of an Art Deco building. These days it goes by the name of Exchange Place Studios, run by Yorkshire Artspace, and provides workspace for more than eighty artists and makers in 60 studio spaces.

In 1922, W.H. Smith erected this building on part of the site of the old Alexandra Theatre and was seen as an extension to the street improvement scheme around Exchange Street.

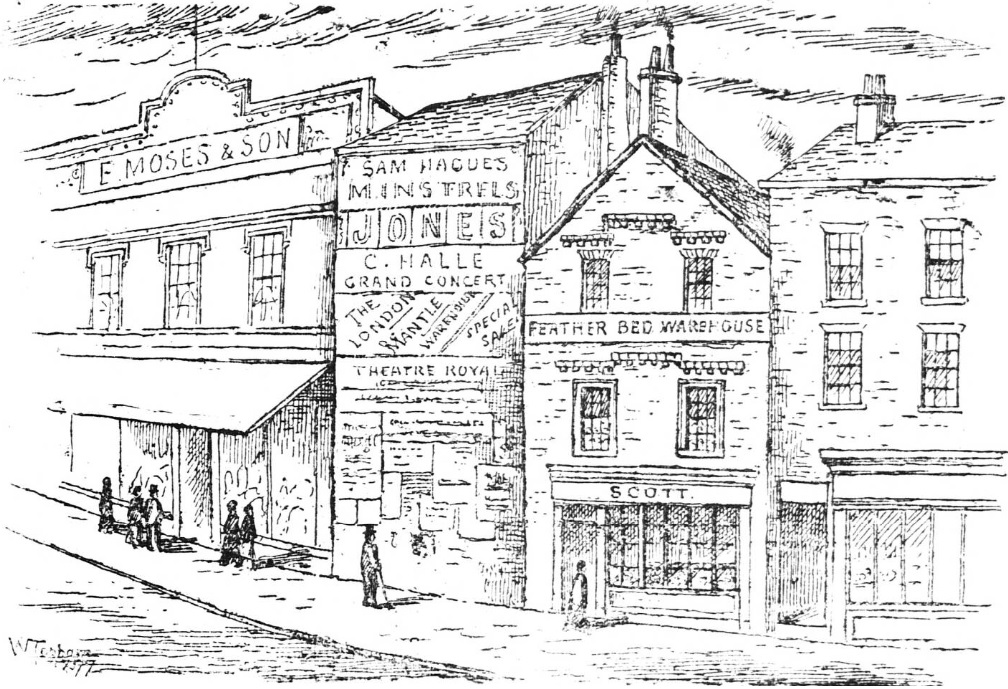

Since 1902, W.H. Smith had operated its wholesale business from York Street, but the growth of the business meant larger premises were required. The chosen site was ideal because of its proximity to the Victoria and Midland railway stations.

“The building itself fulfils the great essentials of good architecture and practical application, and undoubtedly declares its purpose in the scheme of things. The Doultonware facings are particularly suitable for a manufacturing city like Sheffield, and the general quality of the design of the front is most pleasing. With the iron panels in between, the whole effect strikes a modern note in construction.”

The Sheffield Daily telegraph described it as ‘simple and well-proportioned, bearing the distinctive characteristics of other W.H. Smith buildings which were to be found all over the country.’

This wasn’t surprising because the man who had the greatest influence over its design was F.C. Bayliss, superintending architect at W.H. Smith, and Marshall and Tweedy, all fellows of the Society of Architects. Its construction was completed by D. O’Neill and Son of Solly Street, which had been responsible for many large and important buildings in Sheffield.

The transfer between York Street and Exchange Place had to be executed so as not to disrupt the distribution of newspapers. It required careful planning, and with the help of A.B. Beckett, of Broomhall Street, it concluded business at York Street at one o’clock on the afternoon of Saturday 30 September 1922 and was installed in the new building by 6.15 the same day.

The News Despatch Department was in the basement with each district provided for. Every customer was given a numbered box and labelled with the customer’s name. As the papers arrived in the early morning, they were dropped down a chute, counted, and the customer’s orders were made up and boxed. To minimise labour, an electric lift went from the basement to the entrance door where parcels were loaded onto drays and conveyed to customers.

The ground floor acted as a shop where newsagents were able to buy back numbers at a moment’s notice. It seems strange now that the public often went into a newsagent’s and asked for out-of-date newspapers. The Book department was also here with large stocks of literature available for shopkeepers to buy.

On the first floor was a choice collection of stationary, fancy goods, leather articles, and china, that were set out in glass cabinets provided by A. Edmonds of Birmingham for the perusal of customers. Alongside it was the sweet store.

This was a good introduction to the second floor, that housed a vast collection of British and foreign toys, all imported by W.H. Smith itself. They sourced toy makers abroad and the goods went directly to the retailer without going through a middleman and allowing them to be sold cheaper.

The various representatives were housed on the third floor with special rooms arranged so that the firm’s buyers could meet with people and deal with their samples.

On the floors above were stockrooms from where the whole despatch of stock, apart from newspapers and books, were dealt with. On arrival, goods were checked, invoiced, and packed ready for delivery by rail or road. Part of the accommodation was set aside with a comfortable tea-room where customers could buy refreshments at nominal charges.

An innovation at the time was the use of pre-cast hollow concrete floors in its construction, a saving in dead-weight of 900 tons. This was brought to the site ready cast by the Leeds firm of Concrete Ltd and presumably remain.

Much was made about the amount of light that flooded the rooms through ‘modern and efficient’ windows. Mellowes and Co, a Sheffield firm, supplied the steel sashes and casements, and the special design allowed adequate strength to provide ‘walls of daylight’ and fulfilling the requirements of ventilation and safety.

Why was it called Hambleden House?

It was named after William Frederick Danvers Smith, 2nd Viscount Hambleden (1868-1928), who had inherited the business in 1891.

W.H. Smith remained here until 1965 when it moved into part of Sheaf House, built for British Rail, next to Midland Station, where almost all its newsprint business had consolidated. Hambleden House had become too large and would subsequently be taken over by South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive from 1974.

Now thoroughly modernised, the exterior of the building looks much the same as it always did, except for the absence of a large clock that had originally been installed by A.G. Burrell and Co, of Change Alley, and once provided a service to railway passengers hurrying to catch their train.

NOTE: In September 2006, a new company, Smiths News, was created, the result of a demerger of W.H. Smith’s newpapers, magazines, books, and consumables, distribution business.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.