It was Halloween

“Oh how the candles will be lit and the wood of worm burn in a fiery dust. For on all Hallows Eve will the spirits come to play, and only the fruit of thy womb will satisfy their endless roaming.” – Solange Nicole.

Before the rains came. Autumn leaves and a gravestone. Sheffield Cathedral.

*****

In the still of an autumn night

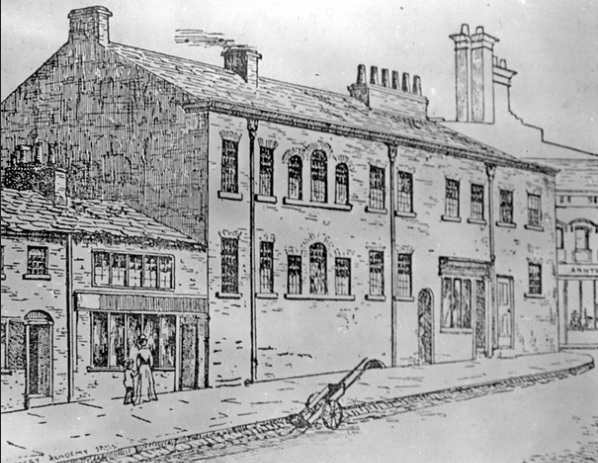

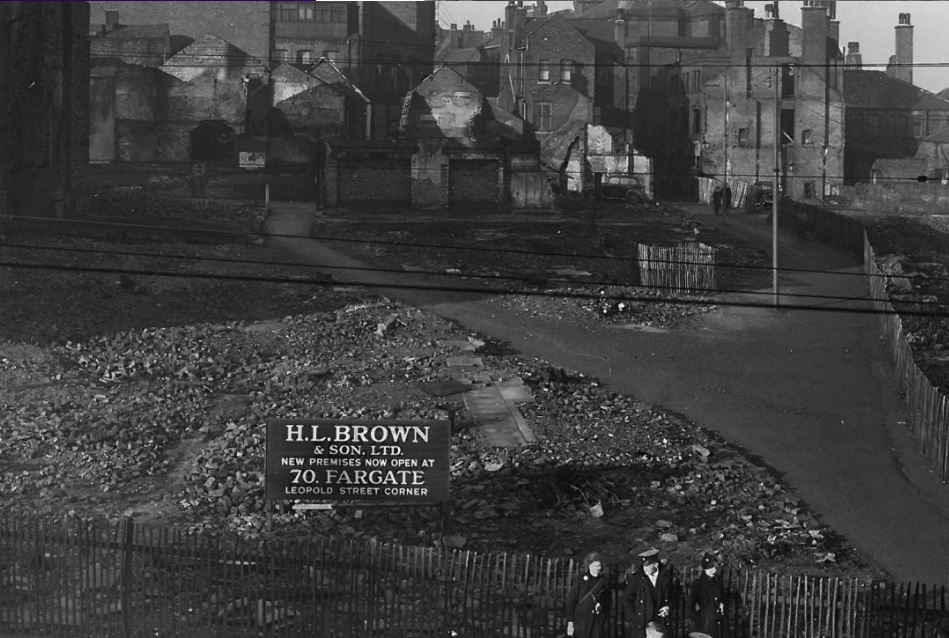

St James’ Row, beside Sheffield Cathedral. It took its name from St James’ Church that stood at the end of St James’ Street (next to where St James House now stands). The church was consecrated in 1789, but by 1945 its roof and fittings had gone, destroyed by the blitz. The shell of the building remained, awaiting the hands of an appreciative restorer, but one never came. It was eventually dismantled in 1950.

*****

It was business as usual

Listeners didn’t suspect a thing. It was business as usual. But it must have been hard for BBC Radio Sheffield presenters to take to the airwaves.

It was the second BBC local radio station to go on the air, launching in November 1967, and yesterday, they heard that Acting Director of BBC England, Jason Horton, was going to “grow local impact in all parts of the country.”

In other words, the BBC are cutting jobs on local radio stations in England, as part of its strategy to become a ‘modern, digital-led’ broadcaster.

Local shows will only survive on weekday mornings and lunchtimes (6am till 2pm) whilst the rest of the output, apart from evening and weekend sport, will be shared either regionally or nationally.

A possible 139 posts will be at risk because of the changes, and a voluntary redundancy drive is being launched. So, who will go? Toby Foster? Paulette Edwards? Howard Pressman?

There will be six regions going forward, covering North West/North East, Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, Midlands, London and East, South, and South West.

It means that outside the eight hours of local programming, the station effectively becomes the radio equivalent of TV’s Look North – BBC Radio North anyone?

*****

Orchard Square and its mega-canopy

In 1987, Orchard Square was ground-breaking, and provided an exciting addition to Sheffield’s shopping scene. And yet, I always got the feeling that people were reluctant to leave Fargate and try something different.

Thirty five years later, Orchard Square finds itself at midpoint.

Nobody could have predicted the internet, a pandemic, and the fact that our shops became stale and generic. And for a long time, we made a mess of the city centre. Like the rest of town, Orchard Square suffered from shop closures and empty units.

But I’m firmly on the side of those that say city centre regeneration will be worth it afterwards. But as I’ve said before, I’m also one of those that hates the slow progress of planning and development.

The future of Orchard Square is going to be leisure, entertainment, and city living.

In January, its owners, London Associated Properties, said it planned to create an events space as well as 13 flats from empty shops.

And now it has submitted a planning application to install a massive canopy in the centre of the square to provide weather protection so markets and events can be held all year. It would be suspended on wires and ‘demountable’ to stop it creating ‘more shade than is desirable.’

The application also includes plans to install more than a dozen awnings above shops to ‘add colour and visual interest’ and ‘provide protection.’

It seems likely that the scheme will get the go-ahead, with Sheffield City Council earmarking £750K of public money from the Future High Streets Fund towards it.

*****

I like colour and light

This is Lightbox, student accommodation on Earl Street, and typical of the things I see at night.

I’m a nightwalker and enjoy seeing Sheffield city centre when most of you are in bed. The use of colour and light makes everything more mysterious and interesting.

But things are changing.

The significant increase in our energy bills means lights are being switched off across the city.

And who can blame anyone for doing so?

But it will make everything seem rather drab.

*****

Soaring into autumn darkness

Is everybody in bed, or are most of these apartments empty? And those rumpled vertical blinds really annoy me.

Velocity Tower should have been 30-storeys high, but construction halted on the 21st floor. When the developer went into administration it was eventually sold to Dubai-based Select Group which also agreed a deal to build the £6.5m Ibis Hotel next door.

*****

A Victorian renaissance

The Montgomery Theatre on Surrey Street is set to receive funding as part of the Future High Streets Fund.

The owners are set to receive £495K to support them in redeveloping the 136-year-old building. The money would go towards making all public areas accessible for the first time as well as changes to the interior design and layout. The upper floors of the building will also be opened.

The grant will help support and expand The Montgomery’s vision of becoming Yorkshire’s leading arts centre for children and young people.

Built in Domestic Gothic-style at a cost of £15,000 in 1884-1886, the Montgomery Hall, as it was called, was designed by Sheffield architect Charles John Innocent (1839-1901) and constructed by George Longden and Son.

The Future High Streets Fund supports landowners to utilise unused space by opening the upper floors of their building and make improvements to frontages on Fargate, High Street and connecting routes such as Surrey Street and Chapel Walk.

Earlier this week, we looked at plans to cover Orchard Square with a huge canopy, and the conversion of the upper floors into eight new apartments. If approved, the scheme is set to receive £990K of funding.

Sheffield City Council’s Finance Sub-Committee will meet next week to discuss both proposals.

*****

Castlegate plans move forward

At last, positive news about Castlegate, once home to Sheffield Castle and Castle Market.

You may remember that Sheffield City Council secured £18m funding from the Levelling Up Fund to develop the derelict site, and it will go to public consultation from next week.

The council hopes to create a new public space which focuses on heritage, culture, and sustainability. It would see the Castle site transformed with new ‘grey to green’ planting, footpaths, a community events space, a de-culverted River Sheaf, and other infrastructure needed to unlock future development.

A ‘Concept Plan’ vision can be seen at the Moor Market between 8-11 November, as well as scheduled presentations at 18 Exchange Street and a Zoom session.

Visitors will be able to comment at Moor Market and an online survey will be available from November 7.

A planning application is due in early 2023, with construction starting in summer and finishing in spring 2024.

However, the Council has estimated that ‘high level’ costs of the proposed changes included in the Concept Plan means the Levelling Up Fund may not be enough to cover all the costs.

*****

“Oh,my poor head.”

I walked into the night to see what I could find. The only person I saw was a drunken young lad staggering somewhere. “It’s the Harley,” he slurred, as I took a photograph.

I remembered Dr Marriott Hall who married Sarah Firth in 1866. She was the daughter of Mark Firth, the steel magnate, who gave them a new house and surgery at this corner on Glossop Road.

And then, I thought of Dr Hall riding his horse along Endcliffe Vale Road in 1878. The horse threw him off and the doctor’s head struck a kerbstone.

“Oh, my poor head,” he complained, and suffered a slow agonising death.

Lastly, I thought of students. Drinking, dancing, and shouting.

*****

Harry Styles was singing

The Gothic Revival church of St Silas lit up like a beacon. It’s a far cry from the cold and gloomy day of February 1869 when the Archbishop of York consecrated this new church in front of a full congregation.

It cost £8K, a gift from Henry Wilson of Sharrow, and the work of John Brightmore Mitchell-Withers.

His Grace read the 24th Psalm, but on this autumn night all I can hear from inside is Harry Styles singing Late Night Talking, which seems appropriate and inappropriate at the same time.

The church closed at the Millennium and is now student accommodation.

*****

And finally… look what happened in 1929

Sheffield City Hall is getting into early festive spirit.

When it was constructed between 1929-1932, the foundations were sunk to a depth of 30ft. The earth that was removed was taken to build a new dirt track for motor-cycle racing, and this became Owlerton Stadium.

*****

©2022 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.