One day soon, Sheffield Castle might give up some of its secrets. The castle was one of the grandest and most powerful in the north of England before it was demolished by the parliamentarians in 1648.

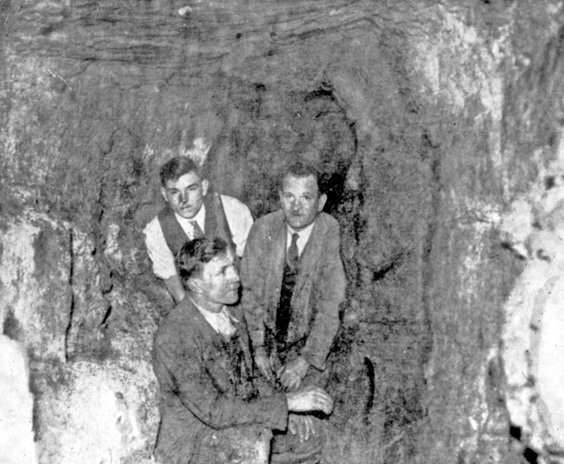

The site of the castle was built over several times, the remains discovered in the 1920s, and covered over once again. And then Castle Market was built over it in the 1960s.

It might come as a surprise now, but during the 18th and 19th centuries there was doubt as to where Sheffield Castle had stood.

Most historians guessed correctly, and from here on, Victorians liked the romantic notion of secret tunnels running underneath the town, supposedly relics from the old castle.

Different generations handed stories down, with tales of hidden tunnels running from Sheffield Castle towards Manor Lodge, the Old Queen’s Head at Pond Hill, and towards Sheffield Cathedral.

We’re no closer to the truth now, but evidence has been uncovered over the years to suggest there might have been some legitimacy to the stories.

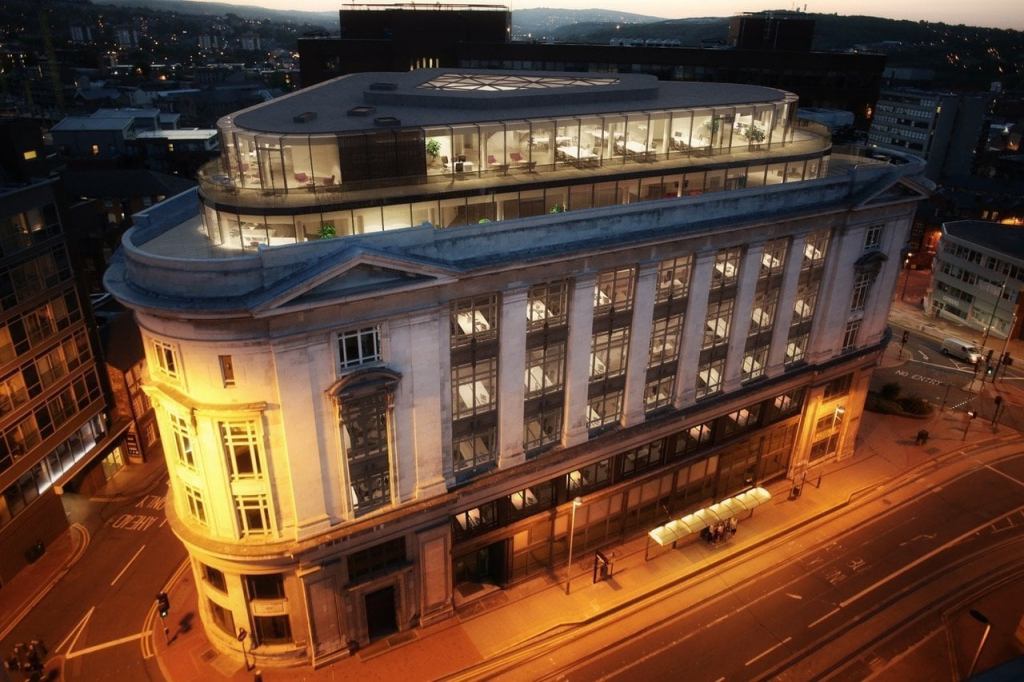

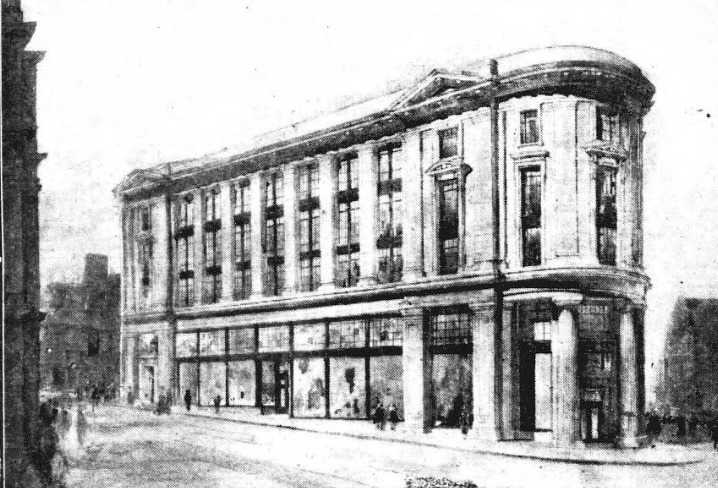

In 1896, during excavations for Cockayne’s new shop on Angel Street, a subterranean passage was discovered, arousing the interest of archaeologists and antiquarians.

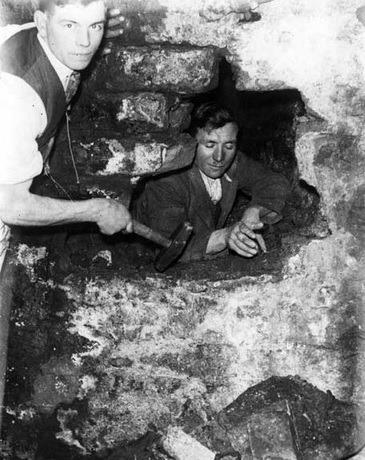

However, it wasn’t enough to excite local journalists who were invited to accompany an exploring party up the passage.

Said one. “The expedition sounded attractive, but when I found that to gain admission it was necessary to crawl through a particularly small entrance, and that on the other side the passage had a covering of a foot of water, my exploring enthusiasm was dampened.”

He took consolation with the foreman’s claims that it was merely an “unromantic sewer,” his view confirmed by the explorers.

Alas, the march of progress ended any further exploration, and the passage was duly blocked up.

And there was another story from the same year, but one that didn’t emerge until 1920, when a retired reporter sent a letter to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph.

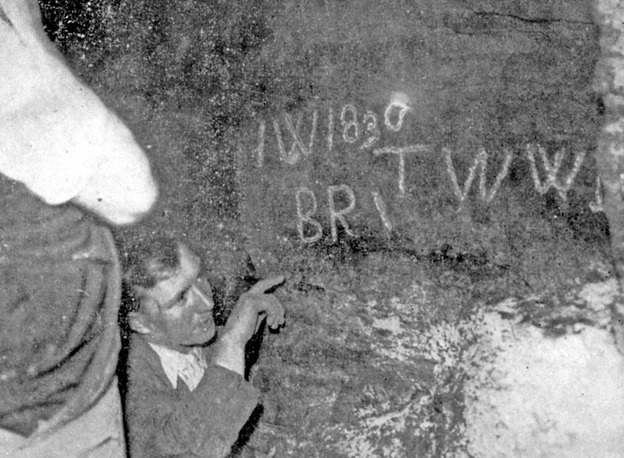

“At the bottom of High Street, at the curve which leads off towards Bank Street, some excavations were made in connection with drainage works, and at a depth of several yards, the opening in the ground cut right through an ancient subterranean way.

“I undertook an investigation with the view of establishing the correctness or incorrectness of the generally accepted theory. The foreman of the works was good enough to detail one of his men to be my guide, and with a lighted candle we began to walk along the passage towards the church. The opening in the direction of the river had been so badly disturbed during the excavations that the ingress on that side was out of the question.

“It was quite plain to see, as we advanced, that the passage had been cut through stone – it was not hard rock, but a rather soft and friable substratum. It was three feet wide, and at first, we could walk upright, but its height diminished a little, and twenty yards or so from the opening where we entered, we had to stoop to make our way along.

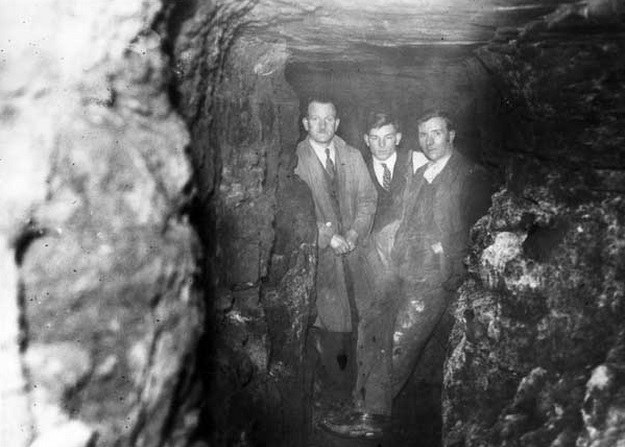

“At length we emerged into a dark cellar, with thralls all around it. The roof was of stone, but without ornamentation of any kind, and, altogether, it had the appearance of one of those underground caverns – crypts, they are commonly, but wrongly, called – in which a business had been carried on hundreds of years previously, and which was, in the first instance, reached by steps from without.

“These steps had disappeared however, and my guide brought me to daylight again up ordinary inside cellar steps, and we emerged into a dilapidated building.

“Pursuing my enquiries, I gathered that the premises beneath which the cellar lay had been for many years, at a remote period, the business place of a wine merchant, And the explanation of the passage was that it was, in all likelihood, a drain to conduct water from the cellar to the river.

“It was objected at the time that the cost of such a drain was altogether against the correctness of this theory; but, on the other hand, it is an established fact that drains of this character were common in medieval times. The residents in a locality would combine to bear the cost and to reap the advantage of such a construction, and, doubtless, if my guide and I had a better light, or if we had been more careful in traversing the passage, we might have seen junctions with the drain coming from the other premises.”

It was a disappointment to those who thought that this was part of a tunnel running from Sheffield Castle to the Parish Church, but the so-called secret passages which ran underground in most towns were either sewers or watercourses.

The story was forgotten, only to emerge again in the 1930s, and subject of another post.