The news that Leeds-based developer Citu has bought the John Banner building at Attercliffe is a major boost for the area. The regeneration of Attercliffe has been a long time coming, and with Kelham Island quickly filling up, developers are finally looking at this neglected part of Sheffield.

The developer already has plans for a nearby 23-acre urban regeneration scheme known as Attercliffe Waterside that will transform brownfield land either side of the Sheffield and Tinsley Canal into more than 1,000 homes.

Citu has suggested that there will be ‘significant investment’ to restore the John Banner building, including the preservation of its façade to retain many of its original features. It is currently a mix of shops and offices with 25 occupiers including Co-op Legal Services, Sheffield Chamber of Commerce, Wosskow Brown Solicitors and EE.

More than once, it has been described as Attercliffe’s flagship building, but most of our younger generation will fail to see its significance.

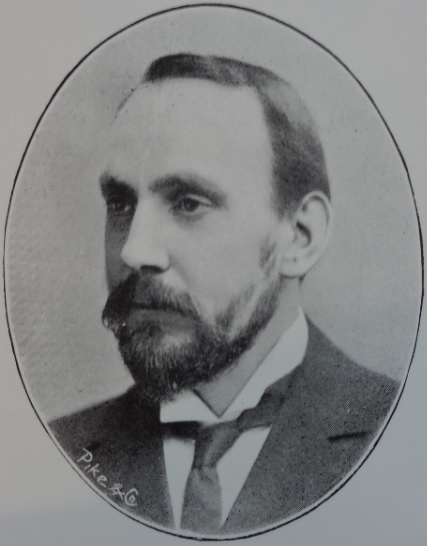

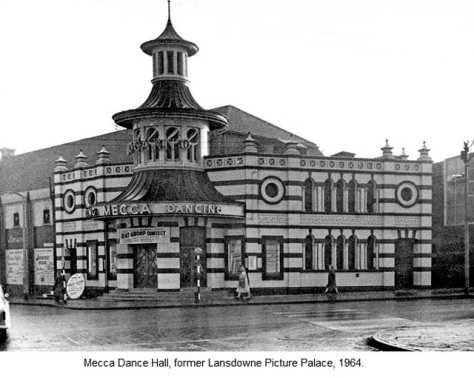

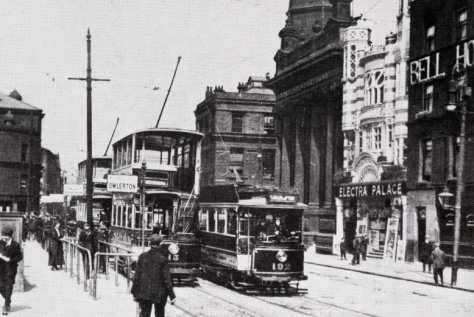

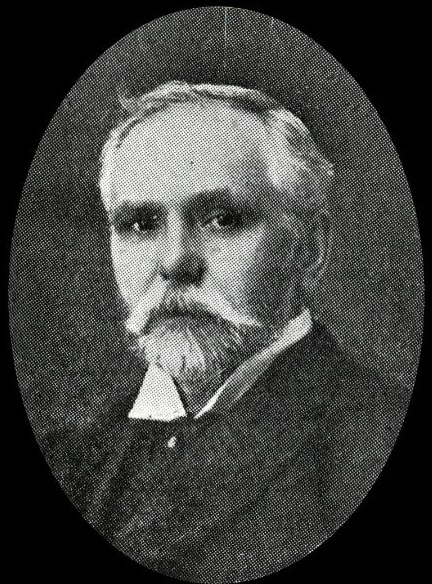

It is named after John Banner (1851–1930) from Kimberley, in Nottinghamshire, who was eleven when his parents moved to Attercliffe. His first venture was a little shop which opened in October 1873, the same week that horse-drawn trams started to run between Attercliffe and Sheffield.

The millinery and drapery business were in what was known as Carlton Road, which together with the adjoining High Street, became Attercliffe Road. It was almost opposite what became Staniforth Road but was then known as Pinfold Lane reflecting the area’s rural aspect.

On the other side of the road were two houses, one with a large orchard attached, and fields stretched from the Zion Congregational Church. The pastor of that church was the Rev. John Calvert who occupied one of the two houses while a doctor lived in the other.

To get the business on its feet, John Banner worked elsewhere for five years while his wife, Sarah, looked after the shop. He eventually gave up his other job and came up with the slogan for his business, ‘The House for Value’.

Seven years after starting, larger premises were needed, and a move was made further up the street almost opposite what became the present building.

Fourteen years later, further development was necessary, and he crossed the road to the present site, building shops in the gardens of the two houses mentioned above that took up the corner at Shortridge Street.

Banner was joined by his four sons – Harold, Ernest, John and Cyril – each becoming co-directors after gaining experience, and two of his three daughters worked in the Attercliffe business, as well as at a new shop on Barnsley Road at Fir Vale.

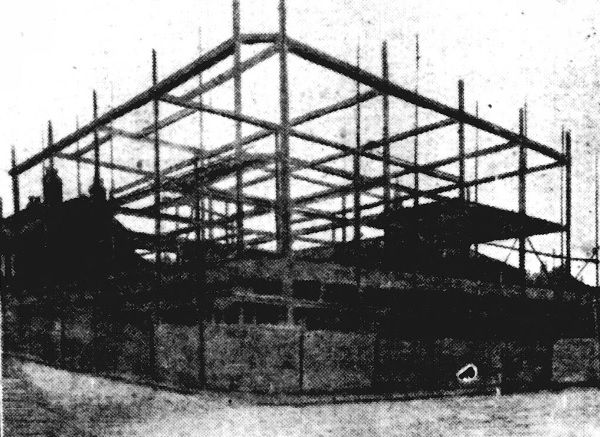

When the opportunity arose, the intervening property between Shortridge Street and Baltic Road was purchased, including a shop which had once been Attercliffe sub-post office. These properties were pulled down and the building of a new shop commenced in 1928 that would fill the space between the two streets.

By this time, the range at John Banner had been developed to include ladies’, men’s, and children’s wear, boots and shoes, and kitchen and household utensils, china, pictures, prams, and fire screens.

It is worth mentioning that the new John Banner department store took six years to complete. It was built in stages and by the time it was finished in 1934 both its founder, John Banner, and its architect, Frank W. Chapman, were dead.

John Banner died at his home on Beech Hill Road in 1930 and was buried at Crookes Cemetery.

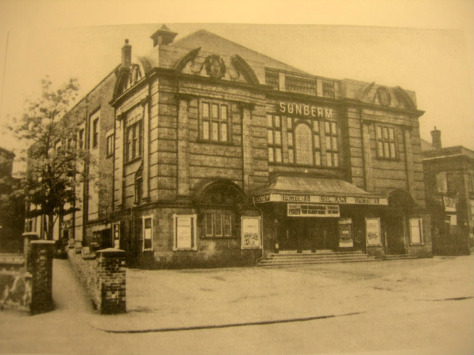

The design of the building was a modern phase of Renaissance, the elevations having pronounced pilasters which ran the height of the two upper storeys, carrying well-proportioned entablature with a parapet surmounted by handsome vases. The pilasters were sub-divided by similar pilasters and the breastwork between the floor filled with effective panelling.

The style of architecture lent itself to the clothing of the steel construction both in pillars and beams which supported the building, and the whole of the casing was finished in dull glazed grey terracotta.

It was built by T. Wilkinson and Sons of Midhill Road, and the steel frame was made by Robinson and Kershaw of Temple Ironworks, Manchester, who had been responsible for other Sheffield buildings including Glossop Road Baths, the Baptist Church at Hillsborough, and extensions to the University of Sheffield and the Royal Infirmary.

The entire frontage of the ground floor was devoted to window display, and a spacious arcade stretched over the whole of the Attercliffe Road frontage on which there were three main entrances. The shop windows were supplied by H.N. Barnes of Fulham with the floor of the arcade covered with marble terrazzo laid by Italian workmen.

The interior lights on all four floors were installed by H.J. Couzens of The Moor, and a novelty was the 300 shop window reflectors and on top of the building, ten attractive Flambean fittings, The first and second floor windows had handsome leaded lights supplied by T. Foster of Norfolk Street who were artists in stained glass and leaded lights.

The last stage of construction, extending the building to the corner of Baltic Road, was built by John Middleton of Hoyle Street with steel skeleton frame manufactured by Thomas W. Ward.

The internal decoration was undertaken by William Chatfield, and it was complemented with wooden counters, shelving, and fittings, that were supplied by Rothervale Manufacturing Company of Woodhouse Mill.

The floors were served by a passenger lift and staircase at the rear of the store in a central position while the first and second floors could be accessed by wooden escalators, the first to be installed in Sheffield.

Shoppers were also fascinated by a system of pneumatic cash delivery tubes, installed by the Sturtevant Engineering Company, that ran from 75 cash stations to a double-sided desk in the offices.

One of John Banner’s sons, Ernest, died in 1931, and by the time the building was completed in 1934, the business was in the hands of Harold, John, and Cyril Banner.

John Banner Ltd survived the Second World War but a decision was made afterwards to sell the business to United Drapery Stores.

As people moved away from the area, the store’s fortunes went the same way as Attercliffe. It suffered a decline in sales, and for a time the basement area was leased to Grandways Supermarket. Along with the ailing fortunes of UDS , the decision was made to close John Banner in 1980.

The building was subsequently divided into offices with retail space on the ground floor. It goes without saying that most of its rich interiors were lost in the transition.

Until this year it was owned by the John Banner Centre which went into administration in May. It has been acquired by Citu which is dedicated to preserving its historical significance.

John Banner Biography

“There was a kindly smile to John Banner and rare civic spirit, devoid of self-seeking, and a sincere desire to express a Christian spirit in service. He had a great sense of loyalty and executive ability in getting things done, and never tired of a good cause.”

These words appeared in the Sheffield Independent following his death in 1930.

John Banner was born at Kimberley in 1851, the son of a carrier, and began work at the age of seven. His parents moved to Attercliffe when he was eleven, and John never forgot the hard struggles of his early life, and of the parents who, if they could not give him wealth, gave him character and good example.

Despite the growth of his millinery and drapery business he was never spoilt by success but looked at life and the struggles of others as he knew them.

“I can never forget those days, and knowing the hard lot that most folks have, it is my bounden duty to try to make things better for them.”

He was a keen Liberal, working in Attercliffe, but refused to seek election for the city council, and was instrumental in the formation of the Attercliffe Liberal Club where he was treasurer for more than quarter of a century. He was on the Sheffield Board of Guardians for 21 years, losing his seat in April 1922, and represented the Guardians on the Attercliffe Nursing Association. He was also on the South Yorkshire Joint Poor Law Committee.

His religious activities were at Shortridge Street Methodist New Connexion Chapel for 36 years. He was treasurer of the Sunday School and the church, a teacher at the Men’s Bible Class, and helped reduce the debt on the church from £1,950 to £250. When he moved to Oakledge at 16 Beech Hill Road, he worked with Broomhill United Methodist Church, and represented it on the Sheffield circuit conference.

John Banner married Sarah Ann Higgett in 1873 and had four sons and three daughters. Sarah died at the age of 81 in 1927.

John Banner died at Oakledge in 1930 and his funeral was at Crooke’s Cemetery after a service at Broomhill United Methodist Church. His shop on Attercliffe Road closed for the day as a mark of respect for its founder.

©2023 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.