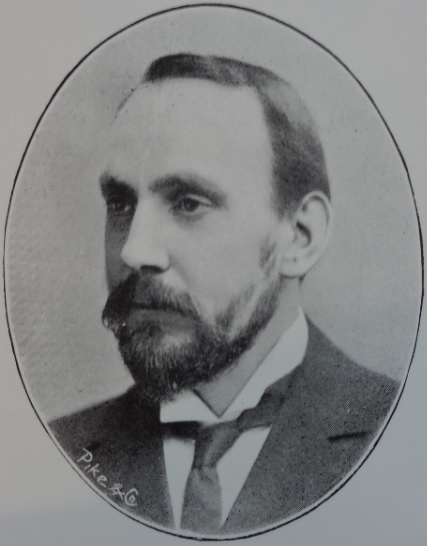

This influential character is relatively unknown in Sheffield’s history. A modest person, he was responsible for one of the city’s iconic landmarks.

Walter Gerard Buck (1863-1934) was born in Beccles, Suffolk, the youngest son of Edward Buck. He was educated at the Albert Memorial College in Framlingham, and acquired an interest in architecture, joining the practice of Arthur Pells, a reputable Suffolk architect and surveyor, where he learned the techniques to design and build.

Walter, aged 21, realised there were limitations to this rural outpost and would need to improve his talent elsewhere. This opportunity arose in Manchester, the seat of the industrial revolution, where demand for new commercial buildings was great. It was here where he gained several years’ experience in large civil engineering and architectural works, including the building of the Exchange Station, Manchester, as well as the Exchange Station and Hotel in Liverpool.

In 1890, his reputation growing, Walter made the move over the Pennines and into the practice of Mr Thomas Henry Jenkinson at 4 East Parade.

Jenkinson had been an architect in Sheffield for over forty years. He had been responsible for several buildings built in the city centre, taking advantage that Sheffield had been one of the last among the big towns to take in hand the improvement of its streets and their architecture.

Buck’s move to Sheffield proved advantageous. Jenkinson had become a partner at Frith Brothers and Jenkinson in 1862, which he continued until 1898, when he retired. He made Walter his chief assistant and allowed him to reorganise the business and control affairs for several years. During this period Walter carried out work on many commercial buildings and factories in Sheffield.

Initially, Walter boarded in lodgings at 307 Shoreham Street, close to the city centre. He married Louisa Moore Kittle in 1892 and, once his reputation had been established, was able to purchase his own house at 4 Ventnor Place in Nether Edge.

Perhaps Walter Buck’s greatest work also proved to be his most short-lived.

In May 1897, Queen Victoria made her last visit to Sheffield for the official opening of the Town Hall. It also coincided with the 60th year of her reign – Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Year.

The visit caused considerable excitement in Sheffield and preparations lasted for weeks. Shops and offices advertised rooms that commanded the best positions to see the Queen. Not surprisingly, these views were quickly occupied, but the closest view was promised in the Imperial Grandstand, specially designed for the occasion by Walter Gerard Buck.

This spectacle was built next to the newly-erected Town Hall, opposite Mappin and Webb, on Norfolk Street (in modern terms this would be where the Peace Gardens start at the bottom-end of Cheney Walk across towards Browns brasserie and bar). It was advertised as ‘absolutely the best and most convenient in the city’, with a frontage of nearly 200 feet and ‘beautifully roofed in’. The stand, decorated in an artistic manner by Piggott Brothers and Co, provided hundreds of seats, the first three rows being carpeted with back rests attached to the back. In addition, the stand provided a lavatory, refreshment stalls and even a left luggage office. It was from here that the people of Sheffield saw Queen Victoria as the Royal procession passed within a few feet of the stand along Norfolk Street to Charles Street.

The next day the Imperial Grandstand was dismantled.

The professional relationship between Walter Buck and Thomas Jenkinson matured into a close friendship.

When Jenkinson died in 1900, he left the business to Walter and made him one of his executors. His son, Edward Gerard Buck, eventually joined the business which became known as Buck, Lusby and Buck, moving to larger premises at 34 Campo Lane.

In 1906, Walter was elected to the Council of the Sheffield, South Yorkshire and District Society of Architects and Surveyors and was elected President in 1930. He was also a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and a member of the council of that body.

Walter also became a member of the council of the Sheffield Chamber of Commerce, a member of the Court of Governors of Sheffield University, a member and director of the Sheffield Athenaeum Club, a member of the Nether Edge Proprietary Bowling Club and vice-president of the Sheffield Rifle Club. It was this last role that he enjoyed best. Walter was a keen swimmer but his passion for rifle shooting kept him busy outside of work.

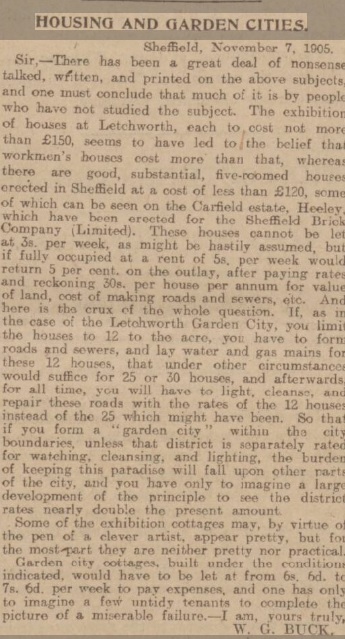

Apart from architectural work Walter held directorships with the Hepworth Iron Company and the Sheffield Brick Company. These astute positions allowed him to negotiate the best prices for the building materials needed to complete his projects.

However, as the new century dawned, it was a role outside of architecture that occupied Walter’s time.

In 1892 the French Lumière brothers had devised an early motion-picture camera and projector called the Cinématographe. Their first show came to London in 1896 but the first moving pictures developed on celluloid film were made in Hyde Park in 1889 by William Friese Greene. The ‘new’ technology of silent movies exploded over the next few years and by 1906 the first ‘electric theatres’ had started to open. In London, there were six new cinemas, increasing to 133 by 1909.

Not surprisingly, this new sensation rippled across Britain and Sheffield was no exception. This had been pioneered by the Sheffield Photo Company, run by the Mottershaw family, who displayed films in local halls. They also pioneered the popular ‘chase’ genre in 1903 which proved significant for the British film industry. The Central Hall, in Norfolk Street, was effectively Sheffield’s first cinema opening in 1905, but the films were always supported with ‘tried and tested’ music hall acts. Several theatres started experimenting with silent movies, but it was the opening of the Sheffield Picture Palace in 1910, on Union Street, that caused the most excitement. This was the first purpose built cinema and others were looking on with interest.

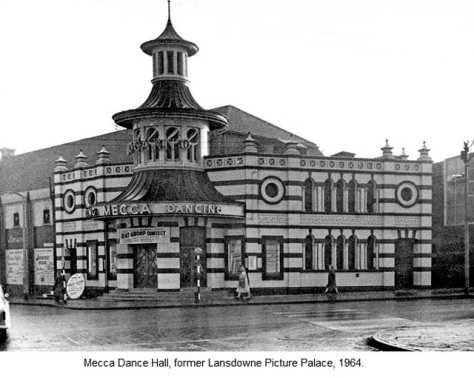

Walter Buck was one such person and saw the opportunity to increase business by designing these new purpose-built cinemas. One of his first commissions was for Lansdowne Pictures Ltd who had secured land on the corner of London Road and Boston Street. The Lansdowne Picture Palace opened in December 1914, built of brick with a marble terracotta façade in white and green, with a Chinese pagoda style entrance. It was a vast building seating 1,250 people. In the same year he designed the Western Picture Palace at Upperthorpe for the Western Picture Palace Ltd.

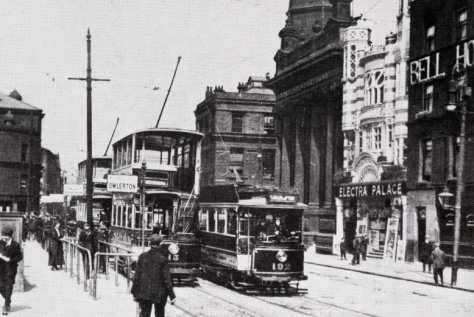

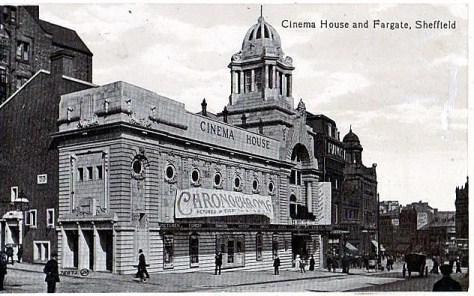

With the knowledge required to build cinemas it was unsurprising that Walter Buck was asked to join several companies as a director. One of these was Sheffield and District Cinematograph Theatres Ltd which was formed in 1910 for ‘the purpose of erecting and equipping in the busiest and most thickly populated parts of the City of Sheffield and district picture theatres on up-to-date lines’. Its first cinema was the Electra Palace Theatre in Fitzalan Square with a seating capacity upwards of 700 with daily continuous shows. Their second cinema was the Cinema House built adjoining the Grand Hotel and adjacent to Beethoven House (belonging to A Wilson & Peck and Co) on Fargate, this part later becoming Barker’s Pool. This was a much grander cinema with a seating capacity of 1,000 together with luxuriously furnished lounge and refreshment, writing and club rooms.

Ironically, Walter Buck did not design either of these picture houses. Instead, they were conceived by John Harry Hickton and Harry E. Farmer from Birmingham and Walsall, but the bricks were supplied by the Sheffield Brick Company, that lucrative business where Walter was a director. It should not go unnoticed that this highly profitable company probably made Walter a wealthy man. It had already supplied bricks for the Grand Hotel, Sheffield University and the Town Hall.

The cinema undertaking was not without risk and Cinema House, which opened six months before the start of World War One, always struggled to break even.

In 1920, far from building new cinemas right across the city, the company bought the Globe Picture House at Attercliffe. The following year they reported losses of £7,000 with Cinema House blamed for the poor performance.

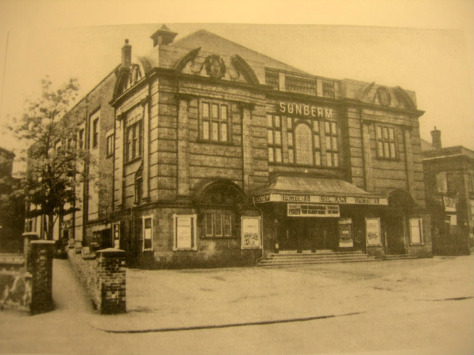

At this stage, it is unclear as to what involvement Walter Buck had with Sheffield and District Cinematograph Theatres. He was also a director of Sunbeam Pictures Ltd, designing the Sunbeam Picture House at Fir Vale in 1922, and the Don Picture Palace at West Bar. He was most certainly a director of the Sheffield and District Cinematograph Company by the late 1920s, and eventually became its chairman. In 1930, absurdly on hindsight, he was faced with a public backlash as the company made the transfer over to ‘talkie’ pictures.

“It was true that some people preferred the silent pictures, but the difficulty was that the Americans were producing very few silent films, or the directors might probably have kept some of the houses on silent films to see if they could hold their own with the talkie halls.”

Walter Buck never retired but died at his home at 19, Montgomery Road, Nether Edge, aged 70, in September 1934. He left a widow, his second wife, Fanny Buck, and three sons – Edward Gerard Buck, William Gerard Buck, a poultry farmer, and Charles Gerard Buck, chartered accountant. Walter Gerard Buck was buried at Ecclesall Church.

It seems the only epitaph to Walter Buck is the Chinese pagoda style entrance of the Lansdowne Picture Palace. The auditorium was demolished to make way for student accommodation, but the frontage was retained for use as a Sainsbury’s ‘Local’ supermarket. Very little information exists about his other work in the city and further research is needed to determine which buildings he designed, and which remain. Any information would be most welcome.