Batchelor’s Cup a Soup, Super Noodles, Garden Peas, Mushy Peas – all recognisable products on supermarket shelves – but how many of you realise that their origins were in Sheffield?

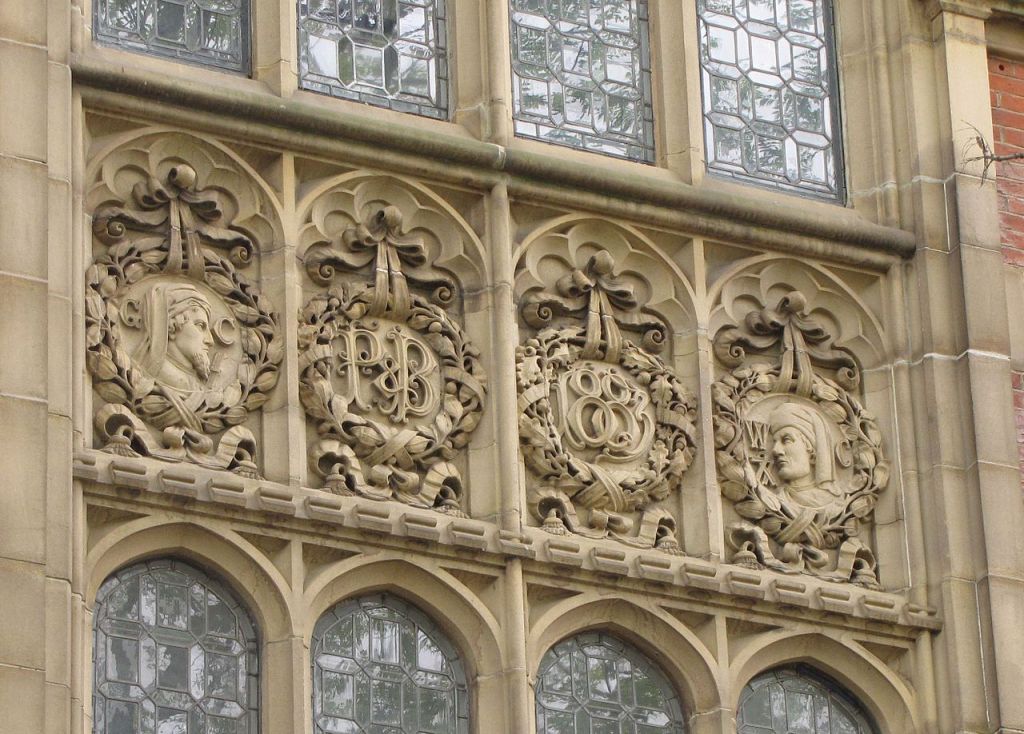

In 1895, William Batchelor, a young tea salesman, set up a small shop and started selling tea in packets, as well as other sundry grocery items.

In an extract from his diary the same year, Batchelor said that he needed £4 by the end of the week to meet his debts, but four years later he was able to write, “What a change in life there has been. What confidence people display in me, both creditors and customers.”

In 1912, he came up with the idea of packing and selling dried peas, which he did in the cellar of a disused Methodist Chapel in Stanley Street, off The Wicker, later moving to an old building in Stanley Lane nearby.

Unfortunately, William Batchelor died on holiday at Bridlington in 1913, leaving a daughter and two sons.

Ella Batchelor, the daughter, aged 22, took over the running of the business, soon joined by her younger brothers, Maurice and Fred.

From being a small family business, Batchelor’s soon grew to national fame, acquiring some of its competitors – Chef Peas, Dinna Peas, and Paull’s of Penrith.

There was rapid progress in the ‘dried pea’ trade with Batchelor’s selling them in 2d and 3d packs, but to the housewife, the preparation of the peas was a lengthy process.

Peas had to be soaked overnight, so when the company devised a ground-breaking new process in 1928, it was an instant success.

Batchelor’s came up with the idea of soaking and canning peas in a factory, henceforth ‘processed peas’ appeared in shops for the first time. Taking a plant near Lady’s Bridge, the company were only able to use small peas in the process, selling them under the Dwarf brand label.

However, in 1932, advances allowed them to use mature peas, extending canning to include Bigga Marrowfat Peas.

In 1935, Batchelor’s needed to increase production and made plans to build a new factory at Wadsley Bridge. In order to finance this the company turned public with an issue of 250,000 one-pound preference shares and 800,000 five-shilling ordinary shares.

The factory was built at a cost of over £100,000 on green-belt land in 1937, opened by the Marquis of Hartington, later to become the Duke of Devonshire. The new works, the largest canning plant in Britain, allowed production to be extended to include canned beans, soups and canned fruits.

At the beginning of World War Two, Batchelor’s was one of the largest suppliers of canned goods to the armed forces – and because there was an embargo on imports of foreign peas, the company set up an agricultural service in the East of England, stretching from the East Riding down to the Weald of Kent, providing about 200,00-acres of land for growing peas. Once cultivated, the peas were sent to new factories in Worksop, Newark or East Bridgford, in Nottinghamshire.

But staff shortages and rationing during the war put a strain on finances, and Batchelor’s was bought by James Van den Bergh of Unilever in 1943, becoming part of Van den Bergh Foods.

Ella Gasking, as she became, retired in 1948 – the same year that Batchelor’s bought Poulton and Noel, a soup manufacturer – and her brother, Maurice, took over the running. A year later, the first dried instant soup was created, chicken noodle flavour, the forerunner to perhaps its biggest success, Batchelor’s Cup a Soup, launched in 1972.

The Sheffield site continued to be Batchelor’s head office, the factory in Worksop was extended, and a plant at Ashford, Kent, was where Vesta dried meals were manufactured.

In 1982, Batchelor’s closed the Wadsley Bridge site, with the loss of 650 jobs, reputedly because the narrow lane and low bridge on its approach restricted heavy goods vehicles going to and from the factory.

Since then, production has remained in Worksop and Ashford, although ownership of the company has changed.

In 2001, Unilever sold Batchelor’s to Campbell’s Soups, with Premier Foods acquiring the UK operations five years later.

Alas, another old Sheffield name that is no longer connected to the city.