It was a cold and clear Thursday night in December 1940. The skies were vibrating with the noise of German Luftwaffe Heinkel HE111 and Junkers 88 aircraft that had crossed over the sea from France. When they reached Sheffield, they dropped parachute bombs that descended at 40mph and exploded when they reached the level of the rooftops sending shockwaves over a wide area. They screeched as they fell, closely followed by thunderous explosions that could be heard right across the city. The streets were scenes of panic, fires raged, and the air was thick with smoke. Sheffield had experienced its first encounter with Hitler’s blitzkrieg, the psychological shock and resultant disorganisation through which the employment of surprise, speed, and firepower, was designed to weaken the city’s resolve.

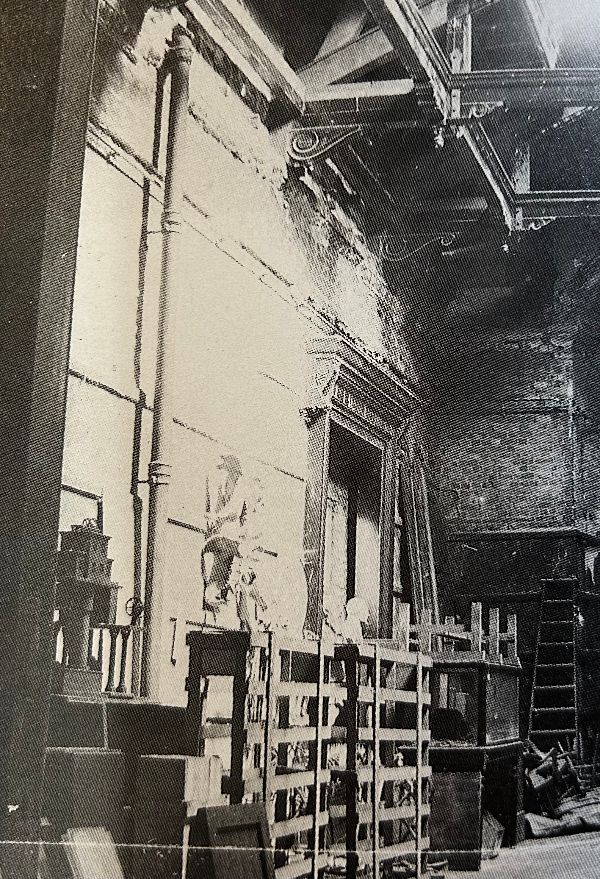

One of the bombs dropped through the glass roof at the back of the Mappin Art Gallery, near Mushroom Lane. It obliterated three of the Mappin’s six galleries, and the shockwave caused major damage throughout the rest of the building, shattering almost every pane of glass, and destroying artefacts. The damage was inconceivable and when daylight came, only the facade, the front two galleries and the Graves Museum extension had survived; the rest of the building was deemed unsafe. Two days later, rain fell and added to the bleakness.

Afterwards, the remainder of the art collection was moved to two premises on the Duke of Devonshire’s estates in Derbyshire, outhouses of Edensor Vicarage and a pub in Pilsley. Meanwhile the shell of the two surviving Mappin galleries was used as a makeshift store, its gutted roof sheeted over.

A year later, the Illustrated London News reported that the Graves Art Gallery, above Sheffield’s Central Library, had opened an unusual exhibition. It consisted of pictures – paintings, watercolours and drawings – damaged in the air raid on Sheffield when they were hung at the Mappin Art Gallery. Some were in the condition in which they were found after the raid, some were restored completely and others only partly.

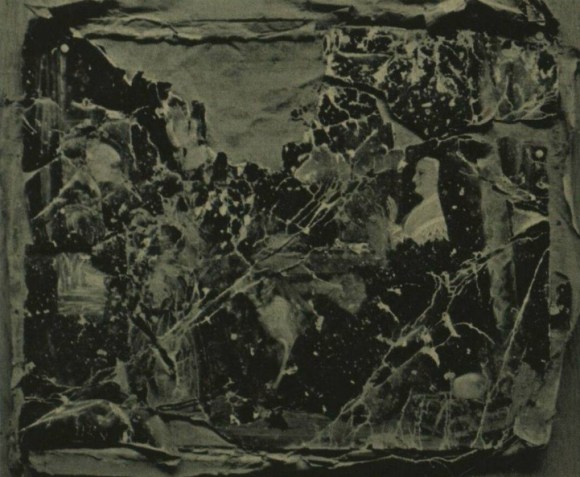

Approximately 250 pictures were damaged by flying glass, bomb blast, or the rain which followed the raid before they could be collected and safely housed. The blast made crazy patterns on the varnish, flying glass caused cuts, some large, in the canvas, and the rain caused those pictures that had been re-lined to separate. But for all this it was hoped to restore between 80 and 90 percent of them.

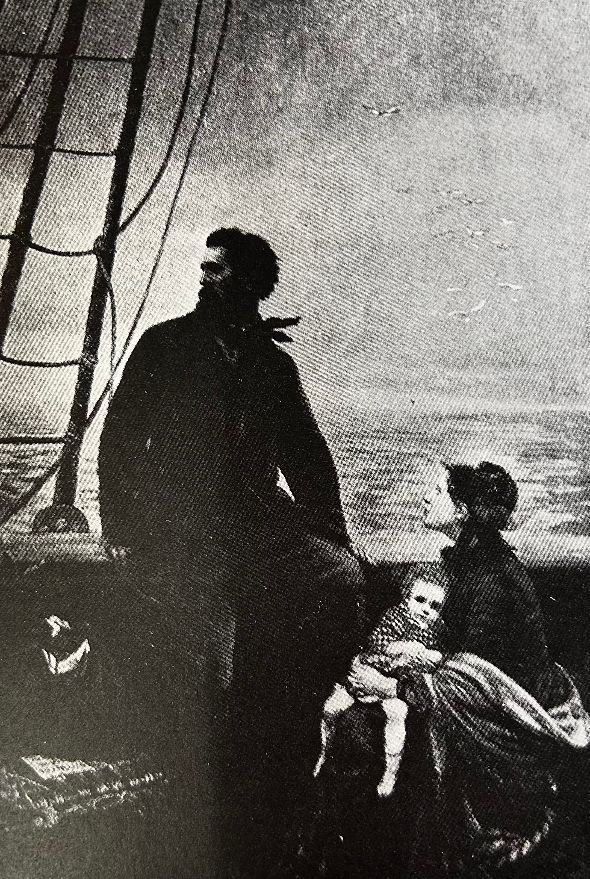

A lot of the work in the Mappin Art Gallery had been bequeathed to the city by John Newton Mappin and later by Sir Frederick Mappin, and amongst the twenty-three works from the original collection which were totally destroyed were key works from like Dorothy Tennant’s The Emigrants and Darnby’s The Vale of Tempe; four of the most important donations made to the gallery, T.C. Gotch’s The Mother Enthroned, H.C. Selous’ The Crucifixion, Noel Paton’s Lux in Tenebris and G.F. Watt’s portrait of J.A. Roebuck; while some important works were so badly damaged that they weren’t repaired until the late 1980s, like Val Prinsemp’s To Versailles, and W.C. Horsley’s The French in Cairo. Among other damaged pictures were works by John Pettie, David Cox, John Phillip, Sir William Rothenstein, G.F. Watts, Dame Laura Knight, Wilson Steer, Orchardson, Sir John Gilbert, and Eric Gill. The total value of damage and loss was estimated at £6,300 by Professor John Wheatley, who had been appointed director of Sheffield Art Galleries in 1938.

War damage payments for the actual works of art destroyed or damaged turned out to be low, reflecting the low value placed on Mappin’s collection.

At the time of the 1941 exhibition between 60 and 70 raid-damaged pictures had already been restored, but it was estimated that the work of restoration would take two or three years to complete. Wheatley explained that Sheffield was reaping the benefit of having appointed in peacetime a practical assistant on the staff.

That person was Harry Frank Constantine (1919-2014), painter, restorer and curator, who had studied at Sheffield and Southampton Colleges of Art and at the Courtauld Institute. He was assisted by his daughter and was only then finding damage that hadn’t been apparent immediately after the raid. Paint loosened by the blast was beginning to flake off, and the greatest difficulty was with the large cuts in canvases, that were carefully drawn together, given a new backing, the cuts filled in with a composition, and the surrounding paint carefully matched.

Constantine took over as director of Sheffield City Art Galleries in 1964 when only the Graves Art Gallery was open. Sheffield had received a major war damage reparation payment, but the ruins of the Mappin Art Gallery hadn’t been touched after the war ended. In 1960, auditors had investigated why the sum for war damage reparation hadn’t been spent, and questions were being asked by the Mappin family. Sheffield Corporation deemed that the rebuilding of the Mappin Art Gallery was low on the list of rebuilding projects, but reconstruction was finally approved in February 1963 and the gallery fully reopened in June 1965.

The Mappin’s Victorian painting collection had been substantially reduced when the building was bombed, and Constantine spent the rest of his career spotting acquisitions in salerooms and in deserted corners of commercial galleries that others had missed. When he retired in 1982, he’d built a reputable collection for the city, curated numerous exhibitions and ensured that the city’s galleries were accessible to everyone.

Many thanks to Professor Michael Tooby and James Hamilton for invaluable information in collating this post.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved