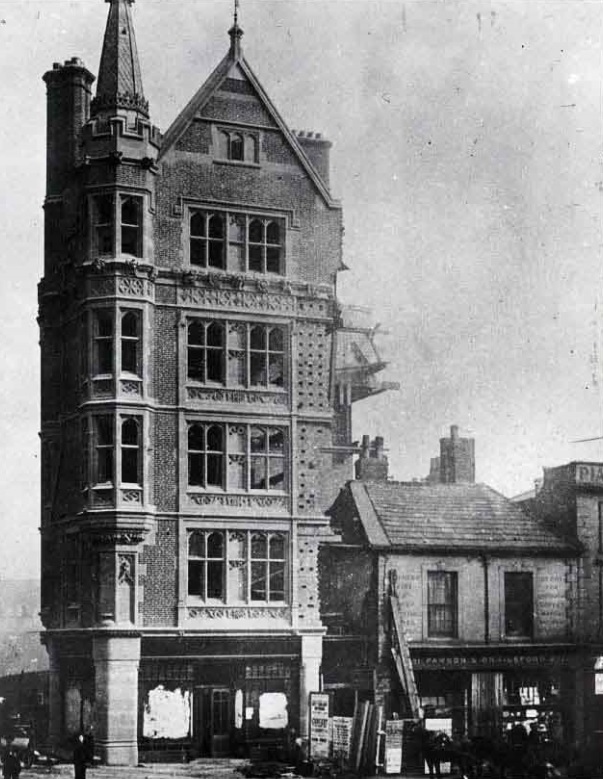

Look at this, Sheffield Town Hall, brand new and clean, seen here in May 1897, shortly before the official opening by Queen Victoria. Within weeks the building was already taking on the tone common to Sheffield, smoke being the culprit, and within decades the Stoke Hall stone was almost black in appearance.

Sheffield’s fourth Town Hall was built between 1891-1896 by Edward William Mountford (1855-1908), one of 178 architects to enter a competition with Alfred Waterhouse as judge.

Mountford was successful despite protests from Flockton & Gibbs, who claimed their “patent” design for municipal buildings had been incorporated into instructions for finalists and used in Mountford’s scheme.

“The architect’s aim, of course, was to obtain the dignity essential for the Corporation’s buildings of the fifth provincial city in England, combined with the maximum amount of internal convenience, and abundant light and air!”

The building contract was awarded to Edmund Garbutt of Liverpool, whose tender amounted to £83,945, but the actual cost, including the site, approached £200,000.

Understandably, the Sheffield public were “up in arms” about the cost, and critical of the expensive embellishments inside and out, protesting that ratepayers’ money was better spent on street improvements and housing for the poor.

The Town Hall was built on an almost triangular site, bought by the council as part of a general improvement scheme, and replacing dilapidated properties either side of New Church Street, a road lost beneath the development.

The principal front faced Pinstone Street (200ft long), although the main entrance was at the centre of the Surrey Street front (280ft long). Its crowning glory was the 64ft-high clock tower complete with Mario Raggi’s bronze statue of Vulcan.

Although the Town Hall clock was designed to be capable of working with bells, they were never fitted, and it wasn’t until 2002 that an electronic bell ringing system was installed, giving hourly strikes with Westminster-style quarter chimes.

On the right of the Pinstone Street entrance were the offices of the waterworks; on the left, the City Accountant’s department. The Town Clerk and members of his department had rooms on the first floor, as were the committee rooms.

On this floor were the Mayor’s reception hall, dining-hall and the Mayor’s parlour, as well as the Council Chamber (60ft x 40ft, and reaching a height of 28ft), light being afforded by traceried windows, and with a public gallery seating 60 people.

The main staircase, 10ft wide, leading to the first floor, was supported on columns of red and grey Devonshire marble, with alabaster balustrades and an ornate marble handrail, the walls being lined with polished Hoptonwood stone.

In other parts of the building, the corridors had floors of glass mosaic and a specially designed dado of antique glazed tiles.

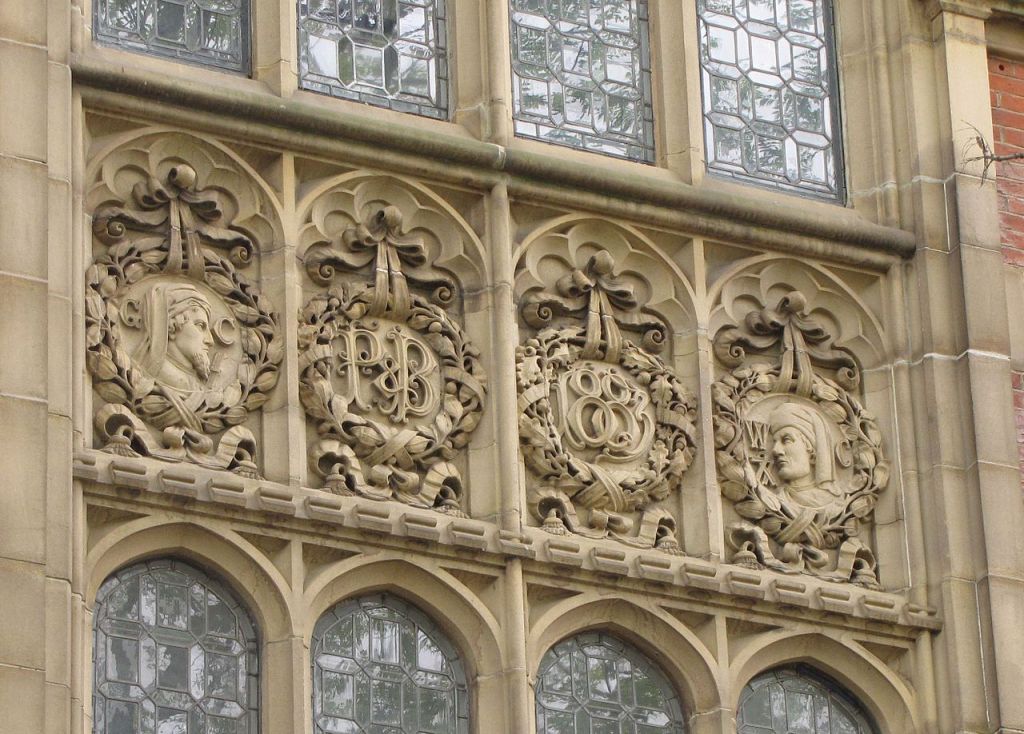

The rich decorative scheme of stone carving, both externally and internally, was devised by Mountford and Frederick William Pomeroy (1856-1924), Royal Academy Gold Medallist, and took pride in Sheffield’s history and the art and skill of its workforce.

The foundation stone was laid by Alderman W.J. Clegg in 1891 and the Town Hall should have been opened by Queen Victoria in 1896, but the death of Prince Henry of Battenberg prevented her from doing so.

The Town Hall was opened by Queen Victoria on the afternoon of May 21, 1897, a story worthy of a separate post.