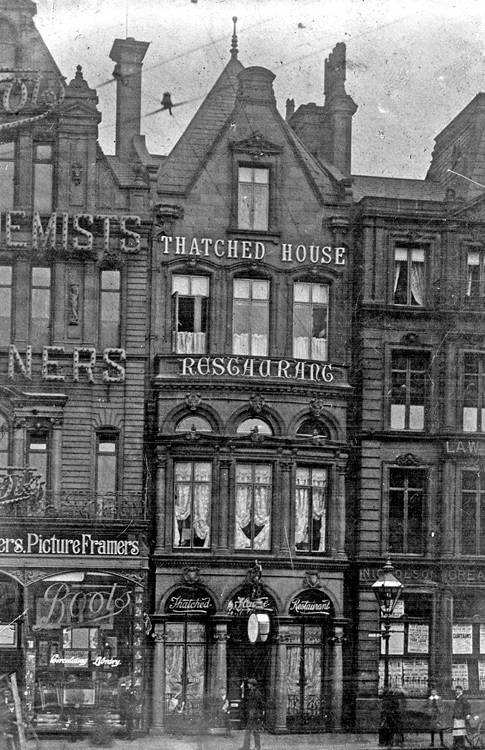

Inspector Woodhead stepped out of the hansom cab that had brought him from the Midland Station to the Thatched House Restaurant. It was a tall, four-storey building, sandwiched between Boots Cash Chemist and an auction house.

He placed his copy of The Times under his arm, doffed his hat at a passing lady, and stepped inside. It was surprisingly quiet for Friday afternoon, but he had no intention of eating. Instead, he made his way towards a staircase that disappeared into the basement.

At the bottom, he pushed open a glass door and walked into a small smoke-filled room. Behind the bar an elderly man stood anticipating his next customer, of which there were few.

Inspector Woodhead nodded to the barman and ordered a tankard of an unusual Sheffield brew. He looked around and found the person he was looking for. A strange young fellow sat at a corner table staring at the glass of whisky in front of him.

Woodhead grabbed his ale and walked over to join him. He sat down beside and carefully placed his hat, newspaper, and pipe, on the table. Then he took a swig of strong northern beer.

“It’s a miserable day,” Woodhead said to his neighbour.

“Do I know you?” scowled the young man.

Woodhead ignored the question. He filled his pipe with tobacco, lit it, and sat back.

“No, sir. You don’t know me, but you could say that I know you.” He puffed at his pipe. “I am Inspector Woodhead of Scotland Yard and I have been looking a long time for you”

“Looking for me? Whatever for?”

“Sir. All in good-time, but first let me get you another drink.”

The young man tugged nervously at the sleeve of his purple suit.

“You are William Burnand Davy, are you not? There are some in this city that call you the Second Marquis of Anglesey behind your back, and in the cafes the waitresses know you as ‘the millionaire.’ You are the grandson of the late William Davy, the well-known proprietor of the Black Swan Hotel and then the Thatched House, a public house that this restaurant is named after.”

“State your business, I cannot sit around all day,” Davy demanded.

“In 1893, your grandfather died leaving a windfall of twelve thousand pounds which came to you when you were 21 years of age.” Woodhead paused to drink. “That was two years ago.”

“Inspector, I cannot see why my financial situation is any concern of yours. What is it you want? Are you demanding money from me? If you are, I must tell you…”

Inspector Woodhead stopped him and smiled.

“You have been a very extravagant young man. You went down to London for a season, spent a good deal of the summer at Bridlington, stayed at the leading hotels in Sheffield, and spent seven months visiting Australia and Ceylon.”

“It was my money to do whatever I wished,” sneered Davy.

“You bought a motor car, and had a chauffeur attired in a striking uniform. The car and its driver were often seen attracting attention outside Sheffield’s hotels. You liked driving, but I understand that you had your licence endorsed in Bridlington for reckless driving.”

Davy swallowed his whisky and the barman brought him another.

“Your ties were the talk of all the ladies, your diamond rings were the price of a manufacturer’s ransom, and your scarf pins included some exquisite gems.” Woodhead paused. “Yes. All eyes were instinctively drawn to you… you were known as carefully-groomed Billy. Trousers that were not properly creased were never worn again, always turned up to show your delicately-coloured silk socks, and your fancy waistcoats and the cut and colour of your suits, might easily have been taken for an imitation of Vesta Tilley.”

“There is no need to be so rude.”

“Facts, my boy, facts,” said the Inspector. “One of your eccentricities was to buy costly presents for girls. Such folly, because after only a few hours acquaintance you’d take her to a jeweller’s shop.”

“My friends told me not to waste money on them,” Davy conceded, “But I treated it as a joke.”

“Ah, yes. Your friends. Those who hung around you for hours and days and weeks. Do you remember the day you walked into the Ceylon Café and joined six of your fellows? You cried, ‘Let’s all go to London,’ and ‘I’ve plenty of money,’ you shouted, and pulled a handful of gold out of your pocket, and to London you all went.”

Woodhead sat back and puffed on his pipe.

“Inspector, you still haven’t told me the reason for your visit.”

“Ah yes,” Woodhead conceded. “About twelve months ago you met Irene Rose Key, a tall, good-looking girl, well known in West End establishments, and in the neighbourhood of Piccadilly. You became infatuated, and impressed her with stories of your fortune, and last May you persuaded her to marry you at Strand Registry Office.”

“Inspector, I think you have the wrong person, because I am not married.”

“Sir. I think you will find that I am correct. Queenie Key was popular in all the music halls and public houses of Leicester Square. And it might have been a happy marriage had it not been for one simple truth.”

“And what might that be?”

“Because at the time of your marriage your financial position became exceedingly embarrassed. Your money ran out.”

Davy laughed for the first time and shouted for another whisky.

“Inspector, this is a joke. I have all the money I need, and if you care to go outside you will see that I have a six-cylinder Belsize car waiting. And to prove there are no hard feelings, I have a sheaf of bank notes and we’ll share a bottle of champagne.”

“It is not a joke. You both came north, but your family refused to accept Queenie, so you returned to London and lived at hotels. Coming to the end of your resources, however, you separated, she returning to the West End and you wanting her back.”

“I have never been married.”

“And so, the purpose of my calling on you today is to discuss the events of eighteenth November 1908. You met your wife on Wednesday morning at a public house in the Haymarket. You both remained until the evening, dined together, and then took a taxi-cab for King’s Cross, your wife under the impression that she would leave you there, that you would return to Sheffield, and eventually leave the country.”

Davy lit a cigarette. “This is beginning to sound like a fantastic crime novel. What am I supposed to have done next?”

“Your wife was wrong. It was never your intention to leave her. You argued in the taxi-cab as it passed along Shaftsbury Avenue, Hart Street, and Bury Street, and into Montagu Street.” Woodhead puffed harder on his pipe. “And in Montagu Street you seized her by the neck, drew a revolver from your pocket and fired two or three shots at her head.”

“I did what?” Davy laughed. “I’m sure I would remember if I had killed somebody.”

Inspector Woodhead unfolded his newspaper to reveal the headline ‘TAXI-CAB TRAGEDY – MURDERER A SHEFFIELD MAN – FORTUNE INHERITED AND SQUANDERED.” He shifted in his seat and faced the young man.

“Sir, there is a simple reason for you not remembering. After you killed your wife, you turned the revolver against your own head and shot yourself.”

“I shot myself?”

“Yes, Mr Davy. You are quite dead.”

“Am I to suppose you have come to arrest a dead man?”

“No. That is not my style anymore. I simply came to make you aware of your crimes.”

“And I have heard enough.” Davy jumped up, gathered his straw boater, and looked down at Woodhead. “I shall leave now and hope to never see you again.”

“Sir. You will not hear from me again. You are free to go. And when you leave by that door, I shall not be able to follow you.”

“I have never heard such nonsense in my life. Good day, Inspector.”

Davy snatched his cane and strode towards the door. He hesitated before opening it and turned back to face the seated Inspector.

“A most grotesque story if ever I heard one. But I have one more question before I leave. If I shot a woman and then turned a gun upon myself, why am I stood here talking to you, and why won’t you arrest me? … No, Inspector. Please do not answer that. Fanciful rubbish. I am leaving.”

William Davy disappeared through the door, closed it behind him, and Inspector Woodhead looked long and hard at it. Then he folded up The Times, relit his pipe, and decided to finish his ale.

“Sir. You are dead,” he murmured. “You have been dead for many years. Only you had chosen not to remember and have sat by yourself in this little room ever since. It was time for you to face the consequences.”

Woodhead felt tired after his long journey and needed to sleep, but here would not do. He closed his eyes, resisted the urge to doze, and when he opened them, he was in an unfamiliar room.

“Time for me to go as well.”

The Inspector gathered his belongings, placed the hat on his head, and left through the same door he had entered. He climbed strange stairs into the dark restaurant and looked about him. How sad, he thought, that it was not a restaurant anymore. Out of the corner of his eye, he caught the shape of a restless black figure.

“Hello, Mr Davy. I see that you are still here. It must be well over a hundred years now.”

Inspector Woodhead stood up straight and disappeared through the glass window that had once been the entrance to the Thatched House Restaurant. Knocked down and rebuilt I should not wonder, he thought.

Outside, the Town Hall clock struck midnight, and Inspector Woodhead turned to look at the building he had just left. BOOTS – PHARMACY – BEAUTY. It was good to see that Boots the Cash Chemist still existed. And then he made his way across High Street, stepped over Supertram tracks, and completely disappeared, never to be seen again.

© 2021 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.