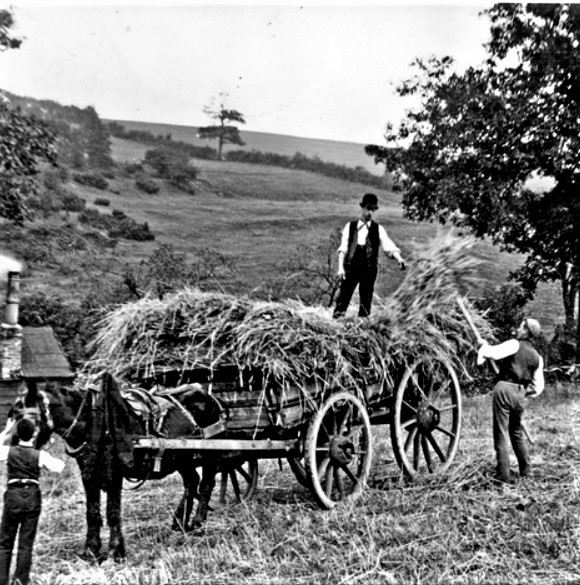

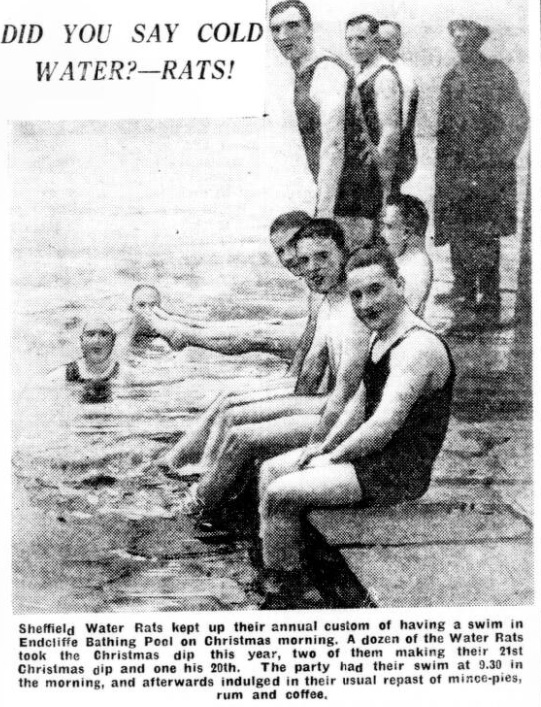

During research into the recent story on William Henry Babington, the Sheffield photographer, this grainy image from a copy of The Swimming Magazine in May 1916 came to light.

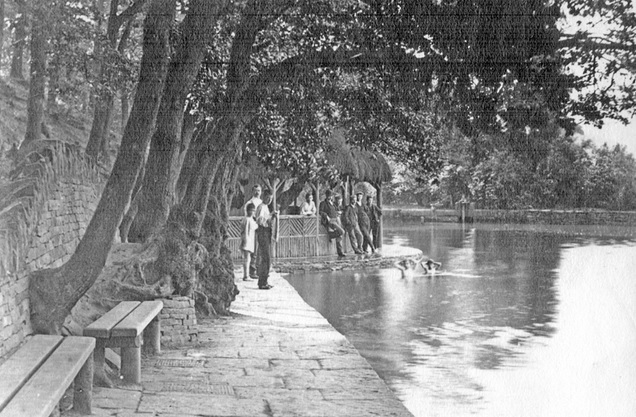

This intriguing photograph features members of Sheffield Water Rats, an ‘all the year round bathing club’, whose members enjoyed themselves in the “fine open-air pool in Endcliffe Woods, about a couple of miles from the centre of town.”

The Water Rats were an all-male club and to qualify for entry into this select family of ‘rats of the pool’ one had to swim winter and summer in Endcliffe Bathing Pool for a period of six years. The ‘King Rat’ was Mr Walpole Hiller who had started about 1894, although he was surpassed by Mr C Foster who taken his first all-year round dip in 1891.

“How many persons would come down to the pool on a foggy autumn morning almost before it was light, plunge into the water, only to find they had a companion in the way of some poor suicide, and yet turn up the next morning as if nothing had happened?”

A tradition for the Water Rats was to take a plunge on Christmas morning, often reported by local newspapers. The custom was to take a dip at 9.30am and afterwards indulge in mince-pies, rum, and coffee.

“They quickly undressed, posed for a ‘snap’ on the edge of the pool, and then plunged in and swam their morning round, coming out glowing with health to dress leisurely and have their customary ‘constitutional ‘swallow.’ There was no shivering or trembling; they behaved with the aplomb of the summer girl basking in the sunshine on some seashore.” – Sheffield Daily Telegraph – 2 January 1923.

Members became older and more ‘youthful’ ones couldn’t make up the numbers. By 1937, the Water Rats tended to only venture out at Christmas, unlike the newer Spartan Swimming Club that had started taking to the open-air Millhouses Bathing Pool every morning.

Endcliffe Bathing Pool had opened after Sheffield Corporation purchased 20 acres of Endcliffe Wood from the trustees of Robert Younge of Greystones. William Goldring was commissioned to adapt the land for public use in 1886, part of which was converting Endcliffe Wheel mill dam as a place for boys and men to bathe.

However, the bathing pool always attracted unwanted attention due to mud and debris washing into it from the adjacent banking.

“I think it is most disgusting,” said one correspondent in 1896, “the water is almost stagnant, in some parts the floor is quite a foot thick with mud and refuse, whilst in other places there is nothing but glass and stones.”

“This pool would be a source of health-giving pleasure to hundreds of men and boys, were it only made clean and wholesome, and the supply kept free from the rubbish which now pollutes it,” said another in 1904.

“A type of woman, and also girls, whose idea of modesty seems to be at a low ebb, persistently come behind railings on the far bank, and also into the enclosure itself. Many of the men are nearly naked, and some of the boys quite so. A park keeper reports coarse language at times,” reported somebody else in 1909.

Endcliffe Bathing Pool closed for cleaning in 1938 and appears never to have reopened. It was filled in and today is understood to be the site of the children’s’ playground.

© 2022 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.