There is a statue of Vulcan on top of the Town Hall, and the more I look at it, the more I see him as the protector of Sheffield. And he’s been doing this for 128 years, and when bombs destroyed the city centre in December 1940, one of the local newspapers put a drawing of Vulcan on its front page and the words DEFIANT!

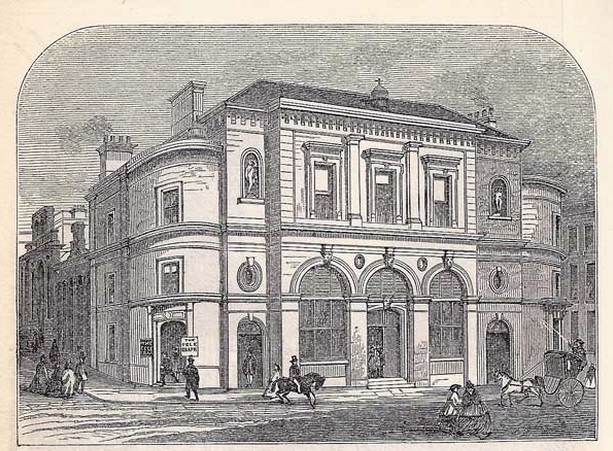

The Town Hall was built in Renaissance Revival style by Edward William Mountford, a London architect, who also designed Town Halls at Battersea and Lancaster, as well as the Old Bailey.

Work began in 1890 and finished by September 1896, but it wasn’t until 1897 that Queen Victoria officially opened it.

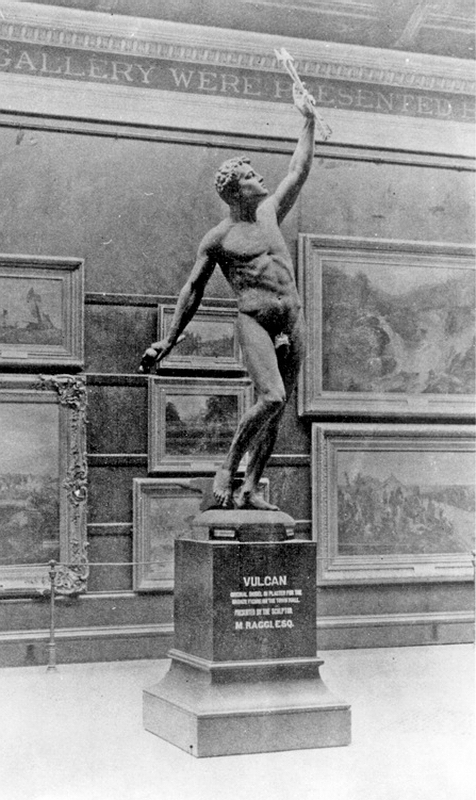

Mountford had wanted something special to stand on top of the one hundred feet clock tower and chose an Italian, Mario Raggi, to create the Vulcan statue.

Vulcan, the Roman God of the furnace, the patron of all smiths and other craftsmen who depend on fire, was adopted as a symbol of Sheffield in 1843.

Mario Raggi was born in Carrara, in Tuscany, in 1821, notable for marble used since the time of Ancient Rome, and it was no surprise that Raggi became interested in sculpture.

He trained at the local academy, and then studied in Rome under Pietro Tenerani before moving to London in 1850 where he first worked for Raffaelle Monti, and then under Matthew Noble.

Raggi exhibited at the Royal Academy and was famous for memorials to Benjamin Disraeli at Parliament Square and Gladstone at Albert Square, Manchester. He also completed three monumental statues of Queen Victoria in Hong Kong, Toronto, and Kimberley in South Africa.

In 1875, he set up his own workshop at Cumberland market, between London’s Regent’s Park and Euston Railway Station, at 44 Osnaburgh Street.

I have the first possible reference to our Vulcan… and that is in 1892 when Signor Raggi had almost completed a standing statue of Vulcan, ‘with a hammer in his right hand, his right foot resting on an anvil and in his left hand, held aloft, three arrows, and intended for Sheffield Town Hall.’

Vulcan is seven feet in height (although other measurements of nine and eleven feet have been given)… and modelled from a Life-Guardsman. It was cast in bronze at the foundry of Henry Young and Co, Eccleston Works, Pimlico.

For a long time, the original plaster cast version was on show at the Mappin Art Gallery until it became irreparably damaged, due to frequent moving to avoid air raids during World War Two and was broken up and discarded.

The bronze statue was erected in 1896 by Cromwell Wiley Hartley, a daring Sheffield steeplejack who completed the task in fierce winds that threatened to dislodge him, but he managed to securely bolt Vulcan to its foundation.

The following year, Hartley climbed the tower again, and fixed an electric light in Vulcan’s extended hand to celebrate the visit of Queen Victoria, then stood on the head of the statue earning him the title as the ‘man with the iron nerve.’ A photograph was taken at the time, by Mr Taylor of Norfolk Street showing him in this risky position but appears to be lost.

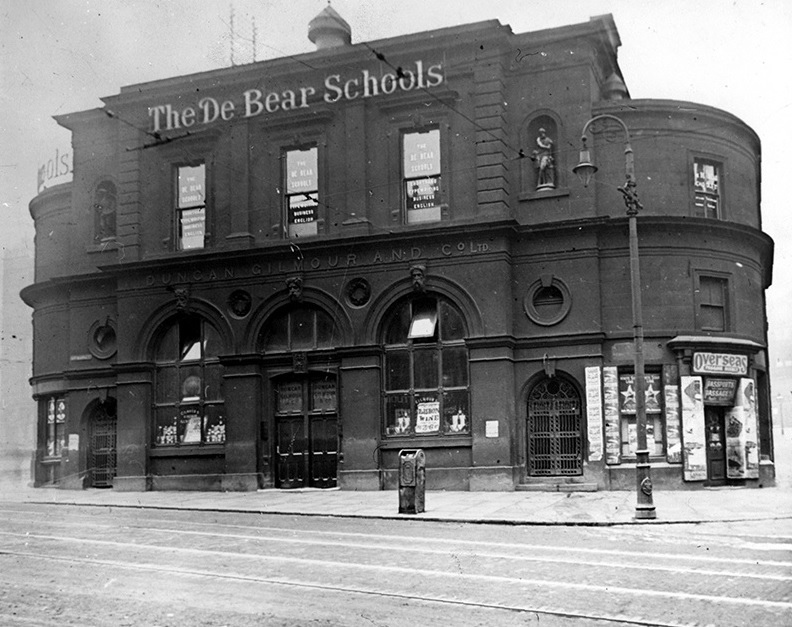

In 1926, Reginald T Rea, the manager of the Albert Hall, which stood on the site of the former John Lewis building, erected a telescope in Barker’s Pool which focused on the statue of Vulcan. It was intended as a publicity stunt and the one penny proceeds from looking through the telescope went to Sheffield hospitals.

It was an enormous success, with an average 2,500 views a day, and the suggestion is that it became a permanent attraction. There is reference to a telescope in World War Two, and through this a story emerged that Vulcan had lost his delicate parts during an air raid. (He appears to be intact now).

While Vulcan is made of bronze, he now has a green patina, the result of a slow corrosion process, which I’m told should not affect his future.

Another model of Vulcan was made at the same time, based on Raggi’s Sheffield original, cast by the Gorham Manufacturing Company, Providence, Rhode Island, and placed outside its headquarters in 1894. It differed slightly because while ours was nude, the American version wore a loin cloth. Alas, its whereabouts is unknown.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved.