In 1924, the author J.H. Stainton wrote in The Making of Sheffield, “It is fairly safe to say that practically half the citizens of Sheffield at the present time know nothing of Mr Emerson Bainbridge, yet in his day he was assuredly one of Sheffield’s big men.”

Now, it is probably a fair bet that nobody in the city has ever heard of him.

Yet, at the time of his death in 1911, he was called “a striking personality,” and responsible for Bainbridge Building, the resplendent Victorian building that stands on the corner of Surrey Street and Norfolk Street.

Emerson Muschamp Bainbridge (1845-1911) was born at Newcastle-on-Tyne and studied at Edenfield House, Doncaster. Afterwards, he attended Durham University and served time in nearby collieries belonging to the Marquis of Londonderry.

In 1870, Bainbridge became manager of the Sheffield and Tinsley Collieries, later taking charge at Nunnery Colliery on behalf of the Duke of Norfolk, subsequently becoming Managing Director and setting up his own firm of mining consulting engineers.

In 1889, Bainbridge obtained a lease from the Duke of Portland for the “Top Hard”, or “Barnsley Coal”, under land in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. He then founded the Bolsover Colliery Company to take the lease and mine the coal, being the man responsible for developing the town that exists today.

Bainbridge also became Liberal MP for Gainsborough between 1895 and 1900, as well as being a JP for Derbyshire and Ross-shire, where he owned a deer forest at Auchnashellach.

Bainbridge provided money to build the YMCA at the junction of Fargate with Norfolk Row, and in the early 1890s spoke of his ambitions to honour his wife, Eliza Jefferson Armstrong Bainbridge, known as Jeffie, who died in 1882.

“I have for some time been struck with the large number of ill-cared for boys and girls in the streets of Sheffield, who, doubtless only represent a small proportion of the large number who are constantly neglected.

“Beyond this, of course, is the great question of neglected training, in consequence of which many of these children are destined to lives of poverty and crime.

“I propose to erect and establish, at some suitable point in the town of Sheffield, a Children’s Refuge, which I would erect in memory of my late wife, and it might be possible to have her name connected to it.”

Bainbridge was a man of his word.

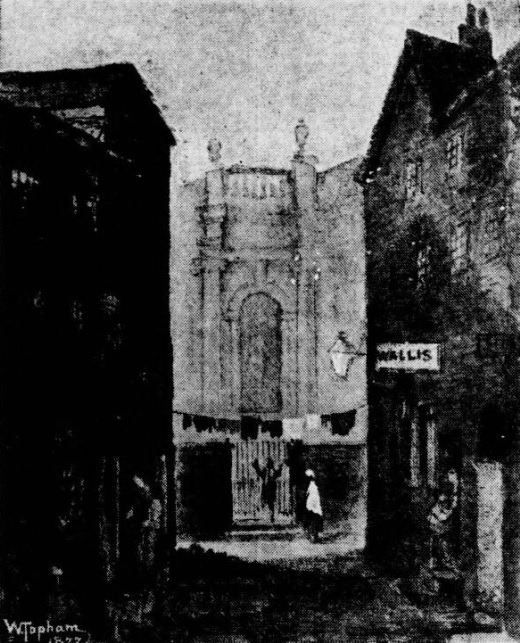

He purchased a plot of land from Sheffield Corporation at the corner of Norfolk Street and Surrey Street, then employed architect John Dodsley Webster to create a spectacular new building that would contain the Jeffie Bainbridge Children’s Shelter.

Construction started in 1893 and was completed in 1894, the total cost being almost £10,000.

The ground floor was utilised for shops and part of the first floor for offices, the rents funding the children’s shelter. The rest of the first floor consisted of a large room capable of accommodating 150 children. Here, ill-clad children suffering from cold and hunger were welcome, and be certain of shelter, warmth and cheap food.

The second floor had been placed, rent free, at the disposal of the local Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. There were dormitories for more than twenty juveniles, also rooms for committee meetings and for caretakers and porters.

The Jeffie Bainbridge Children’s Shelter was officially opened by the Duke and Duchess of Portland on Friday 28 December 1894.

There were five shops underneath, numbered 49-55 Surrey Street, and 104 Norfolk Street. Birds Restaurant, opened by William Bird on a ten-year lease, occupied No.53, although the business collapsed several years later, probably the result of being refused an alcohol licence, something that rankled with the professional men who visited. Next door, Jasper Redfern had a photography shop while William Cole had a piano business at 104 Norfolk Street.

The NSPCC moved upstairs in 1895, but in 1899 Emerson Bainbridge gave them £200 as consideration for removing their shelter to Glossop Road.

The Jeffie Bainbridge Children’s Shelter served over a thousand meals every month to destitute children and appears to have survived until at least 1907. Afterwards, it became a Maternity and Welfare Centre, instigated by the Sheffield Infantile Mortality Committee, where women went for advice and consultations, and to buy dried milk at cost price for bottle-fed babies.

However, the biggest change occurred in 1914, when a portion of the Bainbridge Building was converted into the Halifax Building Society. Most of the shops were taken, with plans created by W.H. Lancashire, Sheffield architects, who clad the exterior in blue and red Aberdeen polished granite, and the interiors with Austrian oak.

In time, the Halifax took the whole building, renting out upper floor offices, culminating in the interior being reconfigured in 1977-1978, when most of Webster’s original features were lost.

The Halifax Bank finally closed in 2017 and the Bainbridge Building has been vacant since.

But let us remember Birds Restaurant, which was unable to serve alcohol to its Victorian customers.

It was recently announced that the pub chain Mitchells & Butlers is opening a branch of its Miller and Carter restaurants, specialising in steaks, in the Bainbridge Building.

There are already Miller and Carter restaurants in the city, off Ecclesall Road South and at Valley Centertainment, the latter of which opened in the summer.