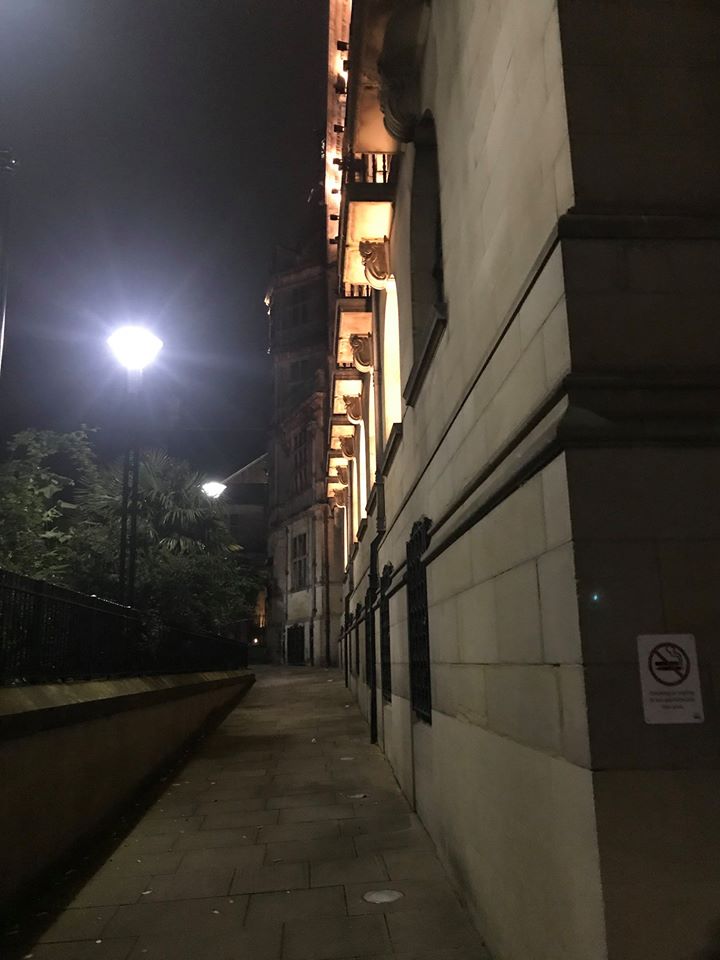

I don’t think many people will realise that this iconic Sheffield building was inspired by a Sears Roebuck department store in Chicago, as well as a nameless shop in Amsterdam. These were the motivation for George S. Hay, chief architect for the Co-operative Wholesale Society, who designed Castle House for the Brightside & Carbrook Co-operative Society in the 1950s.

It has positioned itself alongside Park Hill flats as not being particularly loved. A throwback to the sixties, but like many similar modernist buildings, has matured better with age.

Castle House was built between 1959-1964 for the good old B&C, formed in 1868, who wanted a flagship department store and combined head office in the centre of the city.

The Society’s previous tenure in the city centre had been disastrous. In 1914, it bought land in Exchange Street for a shop, central stores and offices. The First World War delayed work and construction wasn’t started until 1927, at which point the remains of Sheffield Castle were found as the foundations were being laid. The bastion and moats were presented to the public before building recommenced. It was finally completed in 1938, quite a grand affair, only to be destroyed by German bombs in December 1940.

The site was taken over by Sheffield Corporation which had plans for Castle Market (whose construction revealed the remains of Sheffield Castle once again).

In 1950, the B&C Co-op purchased land at the junction of Castle Street and Angel Street and built a temporary one-storey shop, named Castle House, a nod to its former City Stores premises. Accordingly, the one tower heraldic symbol became the familiar logo for the Society.

Castle House was replaced by the five-storey building we know today. It was built of reinforced concrete with Blue Pearl and grey granite tiles and veneers, buff granite blocks, glass and brick. George S. Hay designed it with a blind wall to the first and second sales floors, taking encouragement from the Chicago building.

The interiors were designed by Stanley Layland, the interior designer for the CWS, the crowning glory being a cantilevered spiral staircase linking all floors. The suspended restaurant ceiling was only the second such in Europe.

It opened on 13 May 1964, the total cost of build, including shop fittings, being £925,000.

The B&C planned to merge with the Sheffield & Ecclesall Co-operative Society in 1985, a move voted down by its members, although it changed its name to the Sheffield Co-operative. In 2007, it merged with United Co-operatives, which itself merged with the Co-operative Group shortly afterwards. In 2007, the group decided to close its department stores and Castle House suffered the humiliation of standing empty.

Some trading units remained including food, travel and pharmacy, and

also the Crown Post Office. The pharmacy was closed in 2011 followed by travel and the Post Office.

English Heritage (now Historic England) gave it Grade II listed status in 2009, and in July 2018 Kollider, the regeneration company, announced plans to take over the building, the result of a £3.5million funding deal with Sheffield City Council.

Kollider created a Scandi-style food court on the upper ground floor, Kommune, an all-day dining experience including independent kitchens, brewers, bakers, baristas, book sellers and artists.

The rest of the building has been turned into Ko:Host, an events space, and Kollider Incubator, a work space for innovative, digital and tech entrepreneurs.

Earlier this month, the US tech firm WANdisco, set up in California by Sheffield-born David Richards in 2005, announced plans to relocate sixty staff from its Sheffield head office to Castle House.

The Co-op sign remains, although this refers to the Co-op food store that still occupies part of the building on Castle Street.