A question posed to the readers of the Sheffield Daily Telegraph in October 1869.

“I wonder when ‘Rebecca’ and her well are to appear again, who occupied such a prominent position till taken down for Church Street improvements. Can anyone say?”

The question remains unanswered after 155 years.

To find out more about ‘Rebecca’ we must go back to 1859 when Henry Levy, clothier, of High Street, had given instructions to erect a public fountain at the corner of the Church Gates. Plans had been prepared by Thomas Frederick Cashin, an architect from Bank Street.

The fountain was in the Italian style, about 8ft 9inches in height, surmounted by a figure of Rebecca at the well, which was about 2 or 3 feet high. The completed fountain would have been 4ft 6 inches square.

“The soffit portion will be richly ornamented with water lilies, and the pillastres on each side will be surmounted by ornamental caps, introducing water lilies, and will contain on one side a barometer, and on the other a thermometer. In the front of the erection there will be a niche in which will be placed a shell, and from this shell the water will spring and fall into an ornamental basin. There will be two goblets provided for the use of persons desiring to quench their thirst, and when not in use, these will stand on a ledge.“

The foundation stone was laid at a well-attended ceremony on September 15, 1859, by Horace Mayhew, of London, but the fountain was far from finished.

Weeks later, a letter appeared in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph.

“For weeks I have been wondering not only when it would be finished, but why it was ever begun. I cannot think that our worthy vicar knew what a piece of ugliness was about to be erected on the site he gave.”

Its problems were outlined by Mr Cashin, the architect, who claimed that he had been asked to provide a design for £10, and subsequently obtained permission to spend no more than twenty (about £3,200 today). Fifteen guineas was the amount of the contract for plastering and construction, and three pounds ten shillings for the plumbing. The balance was to be applied to the purchase of Rebecca by Henry Levy but was yet to appear (and didn’t until 1861). The barometer and thermometer, provided free of charge by Chadburn Brothers, had still to be fitted.

To make matters worse, Henry Levy was taken to court by the plumber for non-payment, and he also fell out with the architect.

Although erected with the best of intentions, Rebecca didn’t impress Sheffield folk. “Rebecca is but a poor imitation of the Venus de Medici in Rome,” wrote a correspondent in 1861.

Another assumed to be the statue itself.

“Placed on top of a square fountain with an urn in my hand like a milk jug, and four vases at my feet like Egyptian flower pots, I never was anything to boast of, but now my dress is all in patches, my shoes are toeless, and I altogether look like the woman described by the Italian poet Rinaldo,

‘Non giunge io tu porio,

Fallario est mon gorio.’

Which means, as you doubtless well know, ‘She looks like one whose rags are proof of moral degradation’ – a fine sentiment.”

The structure was made of brick, covered with cement, and might explain why it wasn’t preserved when the fountain was removed for the widening of Church Street in 1866.

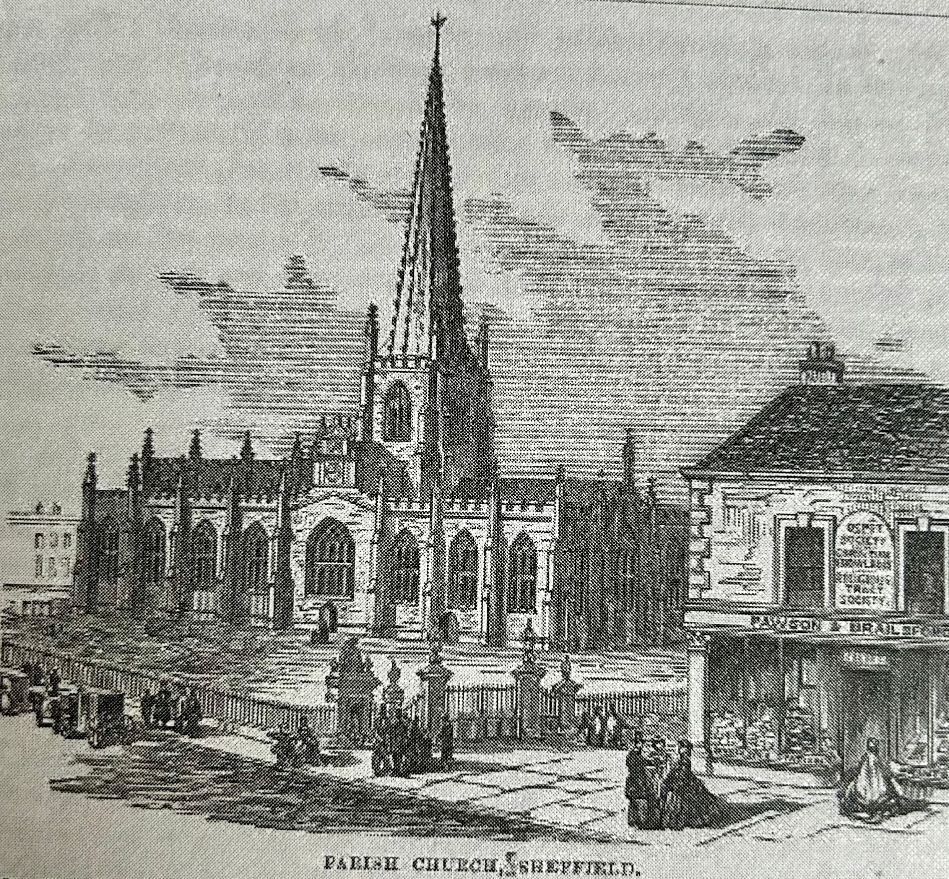

Alas, there are no surviving sketches or photographs of the water fountain. A small photograph of High Street by Theophilus Smith in Sheffield and its Neighbourhood by John Holland, 1865, gave an idea of its appearance from the back, and a small engraving of the Parish Church in Pawson and Brailsford’s Illustrated Guide to Sheffield (first edition) shows a front view of it.

The original church gates still stand at the corner of Sheffield Cathedral’s forecourt next to East Parade. Rebecca’s Fountain would have been to the left of them. In those days, a horse-drawn hansom cab rank would have been nearby.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved