Carmel House, at the top of Fargate, is one of Sheffield’s finest buildings, an example of Victorian architecture that survived when much of it was lost. But appearances can be deceptive, and what is behind that elegant facade is entirely twenty-first century. In 2004, the guts of Carmel House were ripped out, replaced with a steel framework, and all that remains of this Grade II listed building is the frontage (like recent redevelopment works on Pinstone Street).

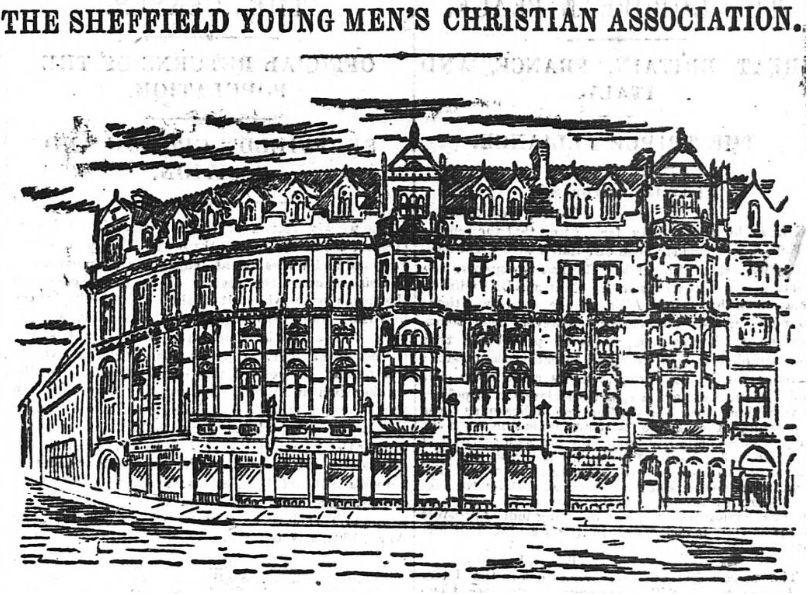

It was built in 1889-91 to designs by Sheffield architect Herbert Watson Lockwood, the subject of last week’s post. Younger readers might be surprised that this was built for the Young Men’s Christian Association, on two plots of land between the then ‘newly built’ Yorkshire Penny Bank, and the offices of Alfred Taylor, solicitor, on Norfolk Row.

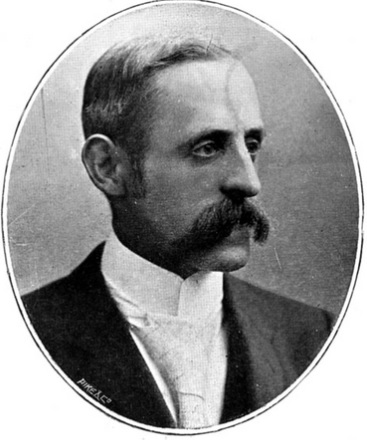

Prior to this, the Sheffield YMCA had cramped rooms on Norfolk Street, but the membership had soared to above 300. It was fortunate to have as its president, Emerson Bainbridge, who wanted to build purpose built facilities. He battled with the Prudential Assurance Company to buy two plots of land, eventually securing the freehold of both in 1888 for £16,000 (including £7,000 out of his own finances), and forming the Association Buildings Company Ltd to raise capital for its construction. (The Prudential would eventually build its offices at the corner of Pinstone Street and St Paul’s Parade).

The building of the YMCA wasn’t without problems.

Work started in August 1889, delayed due to a dispute with Alfred Taylor who was paid compensation for his right to light. Then, while the site was being excavated, it caused subsidence to the adjacent Yorkshire Penny Bank. There was another blow in December 1889 with the failure of its builder, William Bissett and Sons, and work came to a halt. It was picked up in 1890 by Armitage and Hodgson, the Leeds-based builder of the Yorkshire Penny Bank next door.

It was finally completed in May 1891 and opened a month later.

The YMCA had a frontage of 135 ft, and an average height of 54 ft, faced with Holmfirth Stoke Hall stone. It was hand finished with open arcading, above which were lofty gables, the style being late-Gothic, of a Flemish type, the straight portion of the front flanked by projecting oriel windows, carried up two storeys,

The principal entrance was at the corner of Norfolk Row, with a wide arched doorway over which was a stone balcony, having in the centre a panel inscribed ‘One is your Master, even Christ, and all ye are brethren.’

“Symbols of the four evangelists are carved in the corbelling to the balcony over the entrance, six arched panels on the curved portion of the front depicting the six days of Creation and in four other panels the progress of Divine Law from its delivery on Sinai in the two tablets, its development as the scrolls of the law and its completion in the form of the Bible, finishing with a crowned shield bearing on its field the Star of Bethleham. The shields in the main cornice bear the arms or signs of the twelve Apostles. All is by Frank Tory.”

Over the entrance was a handsome projecting lamp carried on a bracketed and enriched wrought iron hoop.

The new premises had six shops on the ground floor, which brought in rental income of about £850 to £975 each year.

Let us now consider its original and lost interior.

From the entrance was a broad flight of stone steps leading to the entrance hall, which was lit from above by a rich stained glass ceiling light, made by Mansfield and Co, of Gresley, near Burton-on-Trent. The floor was laid out with mosaic to a sunflower design.

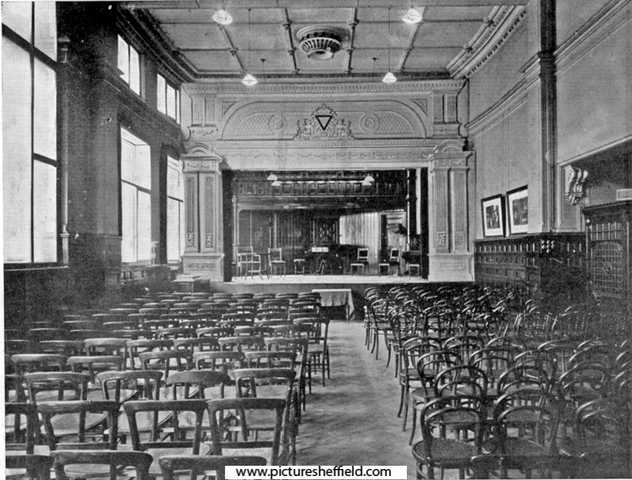

On the right was the secretary’s office, platform entrance to the hall, and a staircase leading to the assembly hall, a well-lit room about 60 ft long, 30ft wide, and 21 ft high, fronting to Fargate. At one end was the public gallery, with a curved front of pitched pine, relieved with arches and octagonal shafts. At the other end was the platform, and over it a private gallery, serving partly as a sounding board, and made of pitch pine and polished walnut.

In the centre, opposite the entrance, was a large bay filled in with a painted window, representing Christ blessing little children, and presented by Emerson Bainbridge. This, along with all the coloured windows had been manufactured by Lazenby Stained Glass Works at Leeds.

The hall seated 250 people, but held 300, exclusive of the two galleries that held 100 more.

To the left of the hall entrance was the corridor to the gymnasium, the principal staircase, and inquiry office. The gymnasium was 44ft long, 35 ft high, and was kitted up by George Heath of Goswell Road, London. At one end was a public gallery, behind which were the dressing rooms, lockers, and bathrooms. The whole of the floor was covered iron and concrete, covered with Lowe’s patent wood block flooring in pitched pine.

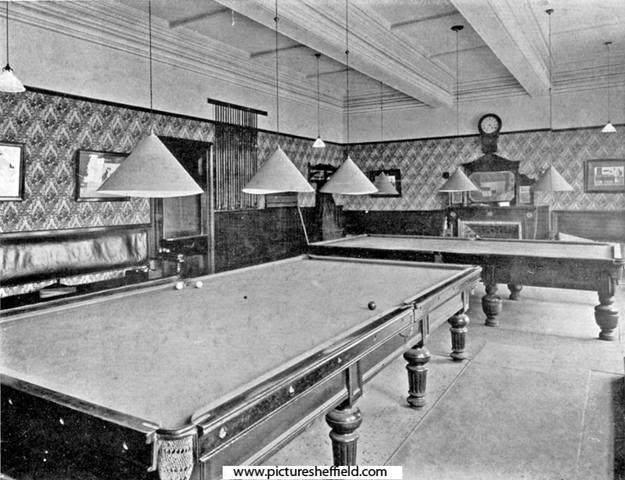

On the mezzanine floor were the honorary secretaries’ rooms and toilets. From this floor, a stone staircase, with covered ceiling, and lit by stained glass windows, rose to a second floor, on which, fronting Fargate, were the library and writing room, fitted with walnut bookcases, meeting room, reading room, annexe, parlour, and refreshment room. At the back were storerooms and caretaker’s house, each communicating with each floor by a hand powered lift.

On the top floor were rooms for the junior department, classrooms and bedrooms.

The dull polished dark oak furniture was supplied by Johnson and Appleyard and consisted of settees and easy chairs, covered in saddlebags, and chairs and curtains in the main rooms upholstered in crimson Utrecht velvet.

The YMCA remained here until the late 1960s, by which time the building, in a prime city centre location, proved too big for its dwindling membership. It moved to smaller headquarters at Broomhill in 1970.

The building’s interior was probably gutted at this stage, redefined as offices, and I hope that somebody will confirm whether this is what happened.

At which point the building became known as Carmel House is uncertain, but the word ‘Carmel’ can be characterised by an awareness of God’s presence in a person’s heart, a sense of the sacred, and a desire for things divine.

As with most Victorian buildings, they can look incredibly attractive, but what lies behind is often unsuitable for twenty-first century use. In 2004, planning permission was granted for the complete redevelopment of the site, including demolition of everything behind the stone facade.

The following year, an important discovery was made during excavations for its new foundations. A medieval well was found on the site, as well as ancient pots and jugs, and possibly dug around the same time as Sheffield Castle was rebuilt in stone about 1270.

© 2024 David Poole. All Rights Reserved