The strange tale of Dr Alonzo Durant, one of Sheffield’s forgotten eccentrics.

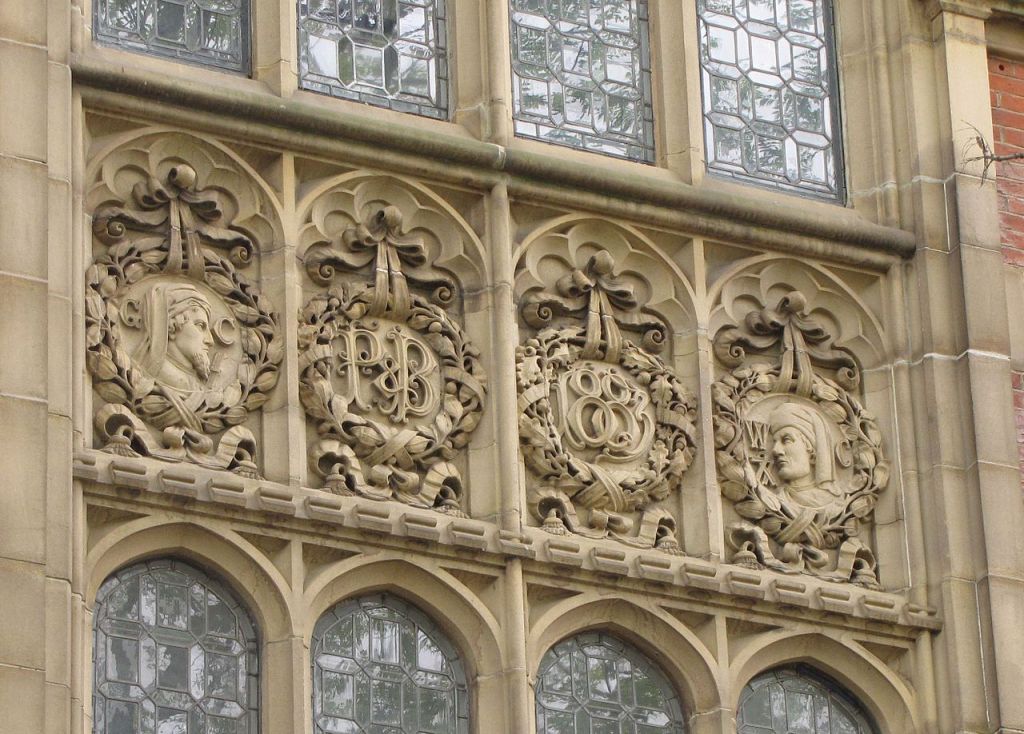

Abacus House, at the corner of Norfolk Street and Norfolk Row, is now home to the Coventry Building Society. According to Historic England it was built about 1791, originally as three houses, later converted into offices.

During the 1850s, one of the properties was tenanted by Mr May Osmond Alonzo Durant, operating as the Medical and Surgical Philanthropic Institution.

Amidst dozens of people who lived or worked here, the story of Alonzo Durant is one of the most unusual and tragic.

He was born in 1816, the eighth son of Colonel George Durant of Tong Castle, between Wolverhampton and Telford, in Shropshire. At the age of 21, he married Catherine Galley much to the disapproval of her father, in Prestwich, Lancashire.

Durant qualified as a surgeon, and by 1839 was a member of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Somewhere along the line Durant settled at Burbage, Leicestershire, living at Tong Lodge, honouring his pedigree, and appears to have lived beyond his means, declaring bankruptcy in 1847.

By 1851, Durant was practising in Ashton, Manchester, before turning up in Sheffield, opening a practice at Bank Street.

As well as offering his services as a surgeon, he claimed to be writing a refutation of a book called The Vestiges of Creation and preparing a book on heraldry “illustrated by engravings of baronial remains in Shropshire, where my ancestors flourished.”

Relocating to the corner house on Norfolk Street, he regularly appeared in newspapers, being described as “a trifle extravagant and not free from eccentricity.”

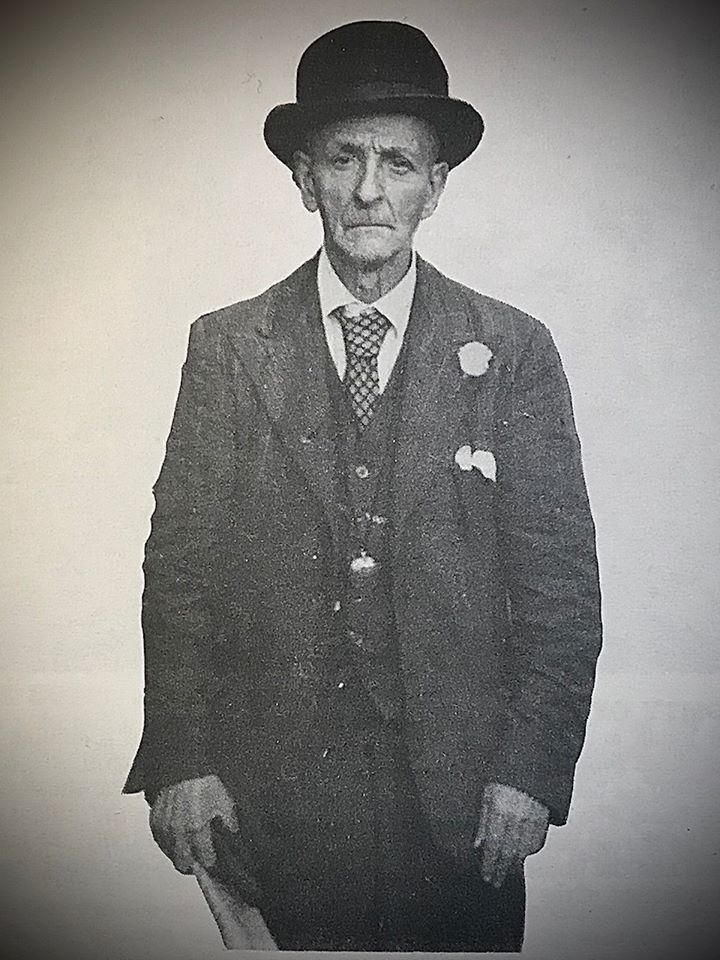

It appears that Dr Durant travelled the streets of Sheffield in a gig with two ponies tandem and a smart boy in buttons at his side. The boy “Joe” carried a horn with which he gave people warning of their approach but had to wait for his master to cry out, “Blow, Joe, Blow.”

Such was the spectacle that a Sheffield theatre mimicked the ritual in a Christmas pantomime, prompting Dr Durant and Joe to take along their horn and join in with proceedings.

Eccentric as this may seem, it didn’t stop Durant preferring charges against William Smith, of Crookes, a musician, for having “used a certain noisy instrument in South Street (now The Moor), for the purpose of announcing a certain entertainment.”

It appears that as Durant and Joe had approached a band playing on top of a large omnibus, by which a large crowd had gathered, the boy had blown his horn to prevent them from being run over, but the louder he blew the louder the band blew their own instruments.

It caused Dr Durant’s horses to bolt, eventually turning into Fitzwilliam Street, throwing the two of them into the air.

Notwithstanding, the band continued playing, and the horses flew up Fitzwilliam Street with the empty gig behind them, running over a man at the corner of Milton Street, and eventually smashing it into pieces against a post.

As one correspondent writes, Durant’s best form of defence was to attack, often pressing charges against individuals, representing himself in court, and causing great confusion with long incoherent speeches.

In 1857, Dr Durant relocated to Crimea House, opposite the Crimean Monument, before inexplicably closing his practice the following year. He sold all his possessions at auction, including “a white Orinoco cockatoo which danced the polka and said anything.”

Dr Durant next turns up at Ramsgate in Kent where, once again, he is recorded as driving through the crowded streets of the town at 17mph, his horn blowing loudly, and even driving on pavements to the danger of pedestrians and perils of shop windows.

By now, he was calling himself Captain Durant, referring to exploits in the East India Service, a fanciful claim, because although he applied for a post in Bengal he never joined.

Whilst in Kent, Dr Durant still took pleasure in appearing in court as plaintiff. On one occasion, after winning a case against a carter accused of damaging his 11 shilling hat, the magistrate remarked:

“Captain Durant [sic] . . . allow me to say a few words about the rapid speed at which you drive through the town. . . It is but a short time since that I myself saw two ladies nearly knocked down by your servant, who was riding, and who apparently had not got his horse under control.”

The ‘Captain’ retorted: “I have driven through the most crowded places and never yet knocked anyone down.”

In 1859, Dr Durant appeared at Ramsgate County Court where Judge Charles Harwood heard that the defendant, “a gentleman of great notoriety, recognised as the ‘Jehu’ constantly driving his tandem through the labyrinths of the place, and keeping the quiet inhabitants in perpetual fear and jeopardy by the peculiar speed of his eccentric performances.”

However, the charge wasn’t about his driving exploits but the mistreatment of a boy, George Ashby, from Ramsgate, whom he took from his father in 1855, promising to pay the boy £5 per annum in wages, but failing to pay up.

George Ashby was the boy “Joe”, forced to blow the trumpet in the streets of Sheffield. Dr Durant never paid him any wages, apart from the odd sixpence now and then for pocket money.

The jury returned with a verdict for the plaintiff and awarded Ashby £15 in damages.

Durant died in strange circumstances in 1861, overtaken by mental illness and probably drinking to excess.

He was seen wearing full military livery on Ramsgate Sands, worse the wear for liquor, walking up to his knees in water with his boots on. He later turned up at the Roman Catholic Chapel where his conduct forced him to be ejected. Durant claimed to be Jesus Christ and the Count de Chambord, and that he expected the King of France to dine with him shortly.

Durant hired a boy and pony chaise to take him for a drive, later abandoning him and jumping over a dyke to chase bullocks. He was next seen setting off for a ramble in the dikes around the River Stour where he was later found drowned.

The boy who had taken him for a drive said he had been with Captain Durant for a year and that he had been locked up in France on account of his madness, that it took several men to take him to prison, and that he had been much worse since he came out.

So ends the strange story of Dr Alonzo Durant, a true Sheffield eccentric, whose exploits could fill a book.